Weekly Checkup

December 4, 2020

The Darkest Hour

’Tis the season for joy, thankfulness, and maybe even a little optimism. Certainly all the recent news around COVID-19 vaccines is reason for some good cheer. But let’s be honest: If you’re a regular reader of the Weekly Checkup, you don’t come here expecting sunshine and puppy dogs, and we’re not going to disappoint you. Daily reported COVID-19 related deaths have only dropped below 1,000 once in the last week, and over 5,000 deaths were reported on Tuesday and Wednesday alone. The vaccines are coming, but in the meantime the pandemic is spiraling. It’s worth stopping to consider the public health crisis we’re in, and what it requires of all of us.

To be clear, COVID-19 has not suddenly become more deadly; in fact, the percentage of infections resulting in death is declining, and there are a number potential causes for the drop. But infection rates themselves have once again soared as colder temperatures, fatigue with social distancing, and now the holiday season have driven more people indoors. We’re also likely seeing in the current data the results of the most travel at any point since the pandemic started. The weather will only be getting colder as we move into winter, and it’s reasonable to expect even more travel over Christmas and New Year’s. It also seems that widespread lockdowns are not in the cards—with a few exceptions—in the near term at least. Concerns about the economic damage and a population much less ready to tolerate extreme measures mean that the best tools for limiting the spread of the virus while we wait for the anticipated vaccines to come online will be mask wearing, social distancing, and frankly not congregating indoors with those outside your immediate household.

But as we said at the start, it’s not all doom and gloom. This week the United Kingdom became the first western country to approve a COVID-19 vaccine, signing off on Pfizer’s two-dose immunization. Here in the United States, the Food and Drug Administration is expected to approve Pfizer’s vaccine for emergency use within the next two weeks, and approval for a second vaccine from Moderna could come before the end of the month. All told, 58 vaccine candidates are currently in clinical trials right now. We could know if a Janssen vaccine candidate is effective by early January, and several vaccines in addition to those of Pfizer and Moderna could be available for distribution by the Spring.

Moncef Slaoui, who is heading up the Trump Administration’s extraordinarily successful Operation Warp Speed, said this week that 20 million Americans could be vaccinated by the end of December, with another 30 million in January and 50 million in February. Slaoui has also suggested most Americans will be vaccinated by June. These predictions seem overly rosy, and according to public health experts would require that there be virtually no hiccups in development, distribution, and take-up. That’s unlikely; for example, just this week Pfizer lowered its estimate for how many doses it will initially produce because of supply chain issues. But assuming that these predictions are even close to correct, we’re still six months away from anything approaching heard immunity. With states such as California rapidly running out of ICU hospital beds, and infection rates skyrocketing, the pandemic could well be entering its worst phase.

The vaccine success really is one of the feel-good stories of 2020. It should be celebrated and serves as a timely reminder about the importance of not stifling medical innovation. But collectively we have to get through the next six months. The pandemic isn’t over just because vaccines are on the horizon. Neither the Trump nor the incoming Biden Administration can drop the ball on testing—which continues to be insufficient—and we’ll need access to improved COVID-19 therapies more than ever.

Most of all, everyone needs to reset expectations. Mask wearing, social distancing, avoiding spending time indoors with friends and extended family—none of it is fun, but we’re all going to need to embrace these inconveniences for a little while longer. English theologian Thomas Fuller famously wrote, “the darkest hour is just before the dawn.” The next few months could be the darkest yet in this pandemic, but we can see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Chart Review: Prescription Drug Price Variation

Julia Demeester, Health Care Policy Intern

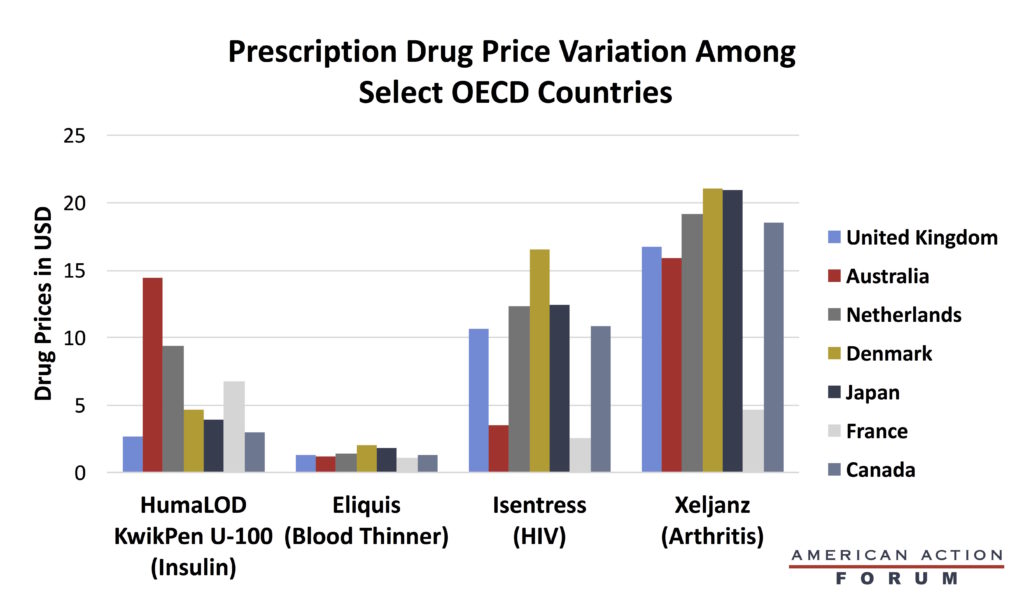

President Trump has long been concerned about the high prices Americans pay for prescription drugs. As Christopher Holt pointed out in his Weekly Checkup before Thanksgiving, Trump’s “most favored nation” (MFN) Executive Order would require Medicare to pay no more for drugs than the lowest price paid by other, economically similar members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (adjusting for certain factors). If the MFN proposal is implemented, Americans could spend $2.57, what France pays, for the HIV medication Isentress instead of $24.92. The savings sound good, but it is not clear if the United States is willing to make the same tradeoffs that these other countries have: In exchange for lower prices, these countries have a limited supply, which forces them to make treatment decisions based on cost effectiveness. In other words, lower prices might expand availability initially, but they could result in less access and painful prioritization of patients later. Further, it is not obvious that central planning of prices results in the lowest-possible savings. Of the selected OECD countries displayed in the chart below, Australia, Denmark, Canada, and the United Kingdom all have a single-payer system, while the Netherlands, Japan, and France each have private payers. Yet the four countries with single-payer systems have the higher prices among this group of countries. This shows that a heavier government presence in drug pricing does not always result in low prices—a lesson the United States would do well to heed.

Data source: House Ways and Means Committee

From Team Health

Policy and the Outlook for Chronic Disease – AAF President Douglas Holtz-Eakin

Controlling the growth of chronic disease in the United States is as complicated as it is important, but it is not hopeless.

Policy Interventions to Mitigate External Risk Factors that Contribute to Chronic Disease – Director of Human Welfare Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes and Serena Gillian

A variety of external and community-level factors contribute to an individual’s risk of chronic disease, including exposure to pollutants and access to fresh food and health care.

Worth a Look

Fierce Healthcare: HHS enlists CVS to pilot administering Eli Lilly’s antibody drug to high-risk patients

The Hill: Moderna to begin testing COVID-19 vaccine in children