Weekly Checkup

August 23, 2019

Moderate Joe?

A few weeks back, presidential contender and former Vice President Joe Biden released a health care plan. Opponents—and to some degree Biden himself—have mostly dismissed the plan as a moderate approach that tinkers around the edges of the Affordable Care Act (ACA). Truthfully, however, Biden’s proposals are hardly milquetoast half measures.

Biden’s plan would deviate notably from several key elements of the ACA. For starters, claims that employees would lose their health insurance were a political concern for the Obama Administration and its congressional allies, so they needed to avoid the erosion of popular employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) in their health care package. Second, the politics of the moment further dictated that they had to limit spending to some degree; the ACA needed to be paid for—at least as far as congressional budgeting was concerned—and there was an intentional effort to keep the total spending under $1 trillion. Finally (and relatedly), there was an imperative to “bend the cost curve,” which put some limitations on just how much federal money could be poured into the health care sector.

Biden’s plan reverses course on all three by removing limitations on federal health subsidies and introducing a public option, which together could increase spending and erode ESI.

Biden is proposing a public option that sounds similar in design to Medicare buy-in proposals others have offered. His public option would be “like Medicare” and would also cover “the full scope of Medicaid benefits.” The Biden public option would “negotiate” like Medicare, although it’s unclear if Biden’s public option would piggyback on Medicare rates or just emulate Medicare’s fee schedule to limit provider payments and thereby lower premiums. Biden’s public option would be available to everyone, explicitly targeting the option to those with ESI. Anyone who does not have access to Medicaid because of a state decision not to expand but who would qualify if it had been expanded would be automatically enrolled in the public option premium-free. States that did expand can transition their citizens as well but will still be required to maintain their contributions to those individuals’ health care costs, effectively penalizing them for expanding Medicaid.

Biden would also change the ACA’s subsidies in three important ways. First, while the ACA set the maximum percentage of income that a family could spend on insurance at 9.86 percent (with subsidies kicking in to cover the rest of the premium), Biden would reduce that percentage to 8.5 percent. Second, the Biden plan would peg the subsidy to more expensive Gold plans rather than Silver, increasing the subsidy amount. Finally, Biden would lift the cap on subsidy eligibility, allowing anyone who pays more than 8.5 percent of their income to receive subsidies no matter how much money they make.

These richer subsidies would flood the health care market with cash to be spent on heftier benefit packages, almost certainly driving up health care spending. Further, Biden would remove the ACA’s constraint on the federal government’s health care liabilities by guaranteeing no American has to spend more than 8.5 percent of their income on health insurance regardless of the cost of that insurance. The “cost curve” would bend, most likely—just the wrong way. And, this unlimited subsidy, paired with a robust public option, could prove attractive to many with ESI, potentially leading to the erosion of ESI that the ACA’s drafters sought to avoid.

Whatever one thinks of Biden’s proposal on the merits, it is hardly a narrow, moderate approach. The Biden plan is a dramatic expansion of the ACA’s health insurance subsidies, and such a shift could have a significant impact on ESI while moving away from the ACA’s few attempts to bend the health care cost curve.

Chart Review

Andrew Strohman, Health Care Data Analyst

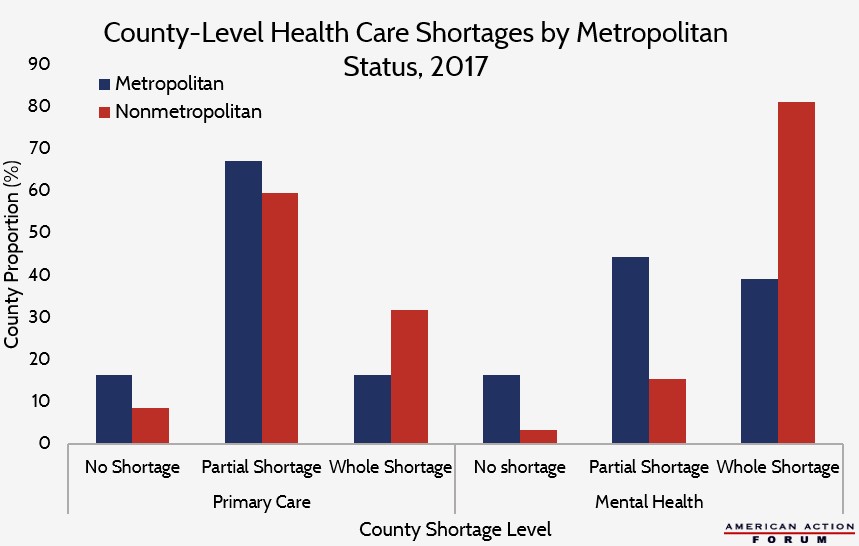

Hospitals are critical for health services in rural areas, anchoring the health care system in many communities, and the introduction of a public insurance option could risk exacerbating the disparity in access to care between rural and urban areas. Navigant recently published a report detailing how a Medicare public option—using Medicare reimbursement rates—would put many rural hospitals at risk of closure by reducing their profit margins, yet these hospitals are already stretched. The graph below shows the strain on medical professionals in rural areas that exists today. Based on 2017 data from the Rural Health Information Hub, 91 percent of nonmetropolitan counties face some degree of shortage for primary care professionals, while 97 percent face shortages for mental health care—rates much higher than their metropolitan counterparts. Whole shortage, partial shortage, and no shortage indicate if a county has an inadequate supply throughout its geographic domain or if the shortage is contained to part of it.

Data are from the Rural Health Information Hub, funded by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy.

From Team Health

New Podcast Episode: Drug Pricing Reform

Deputy Director of Health Care Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes walks listeners through the latest reform efforts in drug pricing in episode 9. Tune in!

Worth a Look

Wall Street Journal: Health Insurers Set to Expand Offerings Under the ACA

Washington Post: The Big Number: How 48 minutes of extra sleep helped these teens