Weekly Checkup

September 20, 2019

Competition and Pelosi’s Prescription Drug Plan

This week we got our first real look at the details of Speaker Pelosi’s plan to lower drug prices, and there’s a lot to talk about. Medicare negotiation is in, of course—though how accurately “negotiation” describes the proposed process is debatable. There is a variation of President Trump’s International Price Index that would function as a maximum price backstop for the negotiations. The plan namechecks other policies popular with Democrats; there is an inflation rebate, retroactive to 2016, for example. Also included are notable reforms to the Medicare Part D program’s incentives that reflect previous work by the Senate Finance Committee as well as AAF, as explained here. Oh, and there’s the little detail that any negotiated prices would act as a price ceiling across the entire U.S. market, not just for federal programs.

But one item that might have slipped your notice is the degree to which Speaker Pelosi and her team misunderstand the concept of market competition.

Pelosi’s plan would authorize the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate “a mutually agreed maximum fair price”—which could be no more than 120 percent of the volume-weighted average price paid by Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom—for up to 250 brand drugs that lack price competition. The Secretary would be required to negotiate the price for no less than 25 drugs annually. So, how does the bill define a lack of price competition? The proposal spells that out: A drug lacks competition if it is a brand-name drug and does not have a generic or biosimilar competitor. That probably sounds reasonable at first blush, but in reality, it’s a pretty arbitrary and, well, ridiculous definition of competition. It’s also an assault on the way we use patents and exclusivity periods to provide incentives for companies to undertake the financial risks associated with drug development.

Take the now-ubiquitous example of Sovaldi, Gilead’s Hepatitis-C cure that was originally launched at $84,000 for a full course of treatment. Keep a few things in mind about this drug. Sovaldi was the first cure for Hepatitis-C; previous treatments sought to slow the disease’s progression, but they didn’t cure it. Also, there is widespread agreement that Sovaldi is a cost-effective treatment, improving quality of life for patients and lowering overall costs to the health care system. But the upfront cost still caused outrage, and without competition and with enough demand, a company can charge pretty much whatever it wants.

Nevertheless, Sovaldi isn’t an example of market failure. Rather, within two years competitors Merck and AbbVie had also introduced comparable Hepatitis-C treatments, and by February of 2015 Gilead had cut Sovaldi’s list price by 46 percent in the face of these competing products.

Under Pelosi’s plan, Sovaldi would be considered to lack competition, because those other drugs are not generic copies but rather other brand-name drugs that are similar in their curative effects. Thus, even though Sovaldi faces competition from similar products, treating the same condition, for the same population, resulting in demonstrable price concessions, Pelosi’s plan would label this situation a market failure.

The Speaker’s rhetoric about competition, good-faith negotiation, and market failures is intended to obfuscate the more fundamental reality: Her proposal amounts to the federal government setting an arbitrary price for a private good and applying that price to the entire U.S. economy. This should be a nonstarter on its face.

Chart Review

Andrew Strohman, Health Care Data Analyst

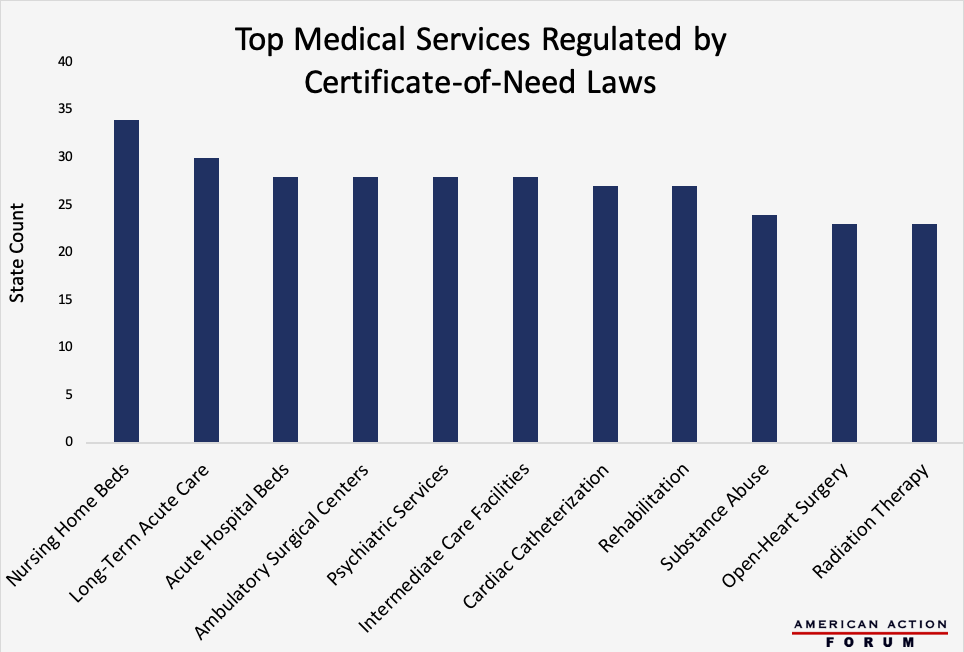

Originally intended to control health care costs at the state level, Certificate-of-Need (CON) laws regulate entry into the market for specific health care services by determining whether given geographic areas have an excess of demand relative to supply. If a radiologist, for example, wanted to establish a private imaging clinic in a state with a CON law covering those technologies, there would have to be evidence of a need for his clinic to fill a gap in supply. Currently, 35 states have some form of CON programs, with three other states having analogous legislation on the books. Those 38 states, however, vary significantly in the types of services they regulate. The chart below shows the top health services regulated by CON laws across the United States, with 34 states regulating nursing home beds and 30 controlling long-term acute care facilities. Some question whether CON laws are better than the free market at determining need, and evaluating the largest examples of CON regulation may provide insight into their overall validity.

Data obtained from the Mercatus Center

From Team Health

Daily Dish: Pro-Leech Drug Policy – Douglas Holtz-Eakin, AAF President

Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s plan for reducing the cost of prescription drugs would drastically diminish the incentives for innovation.

Worth a Look

Wall Street Journal: Israel Prepares to Unleash AI on Health Care

Bloomberg: GM’s Cave-In on Health Care Signals Trouble for Car Industry