Testimony

February 18, 2021

Reflections on the American Rescue Plan

United States Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

*The views expressed here are my own and not those of the American Action Forum. I thank the AAF staff for their insight and assistance.

Chairman Brown, Ranking Member Toomey, and members of the Committee, thank you for the privilege of appearing today to share my views on the American Rescue Plan (“the plan”) and the sister legislation being prepared by Congress. I wish to make three main points:

- The architecture of the plan is largely divorced from the roots of the recession and headwinds to the recovery, and – at best – it will be costly, inefficient, and ineffective;

- The scale and composition of the plan is at odds with the stated goals for economic stimulus toward full employment; and

- A large number of the elements of the plan can only be understood as long-standing and permanent political objectives that are inappropriately advertised as a response to COVID-19.

The Roots of the Recession

In the 20th century, recessions were income-related events. In the prototypical recession, when inventories built up, production was throttled back, layoffs ensued, and household incomes fell. The resulting retrenchment in household spending exacerbated the original problem, and the downturn took hold. Eventually, the shelves became too bare, production ramped up, laid-off workers were recalled, and the dynamics took hold in reverse. Many of the familiar fiscal policies – unemployment insurance, tax cuts, etc. – were designed to provide transfer income to lessen the depth of the recession and shorten its duration.

In the 21st century, recessions have been triggered by financial instability and wealth destruction that spilled over to the Main Street economy. The dot-com bubble burst lead to a mild recession early in the century and the 2007-2008 financial crisis spawned the Great Recession. The same tools were deployed, but with little success. Despite fiscal policy legislation in 2001, 2002, 2003, and 2005, the years after the dot-com recession were labelled the “jobless recovery.” The painful aftermath of the Great Recession is familiar to all.

The COVID-19 recession is unique. Income has risen through 2020, with employee compensation up by 2.0 percent overall, wages and salaries up 2.2 percent, and the massive transfers in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act ensured that disposable income never fell below the level in Q4 of 2020. The recession is not an aggregate income event. Similarly, housing values have risen over 2020, equity markets are up strongly, and household wealth has been bolstered by the large amount of transfer income that has been saved. The recession is not a financial market and wealth event.

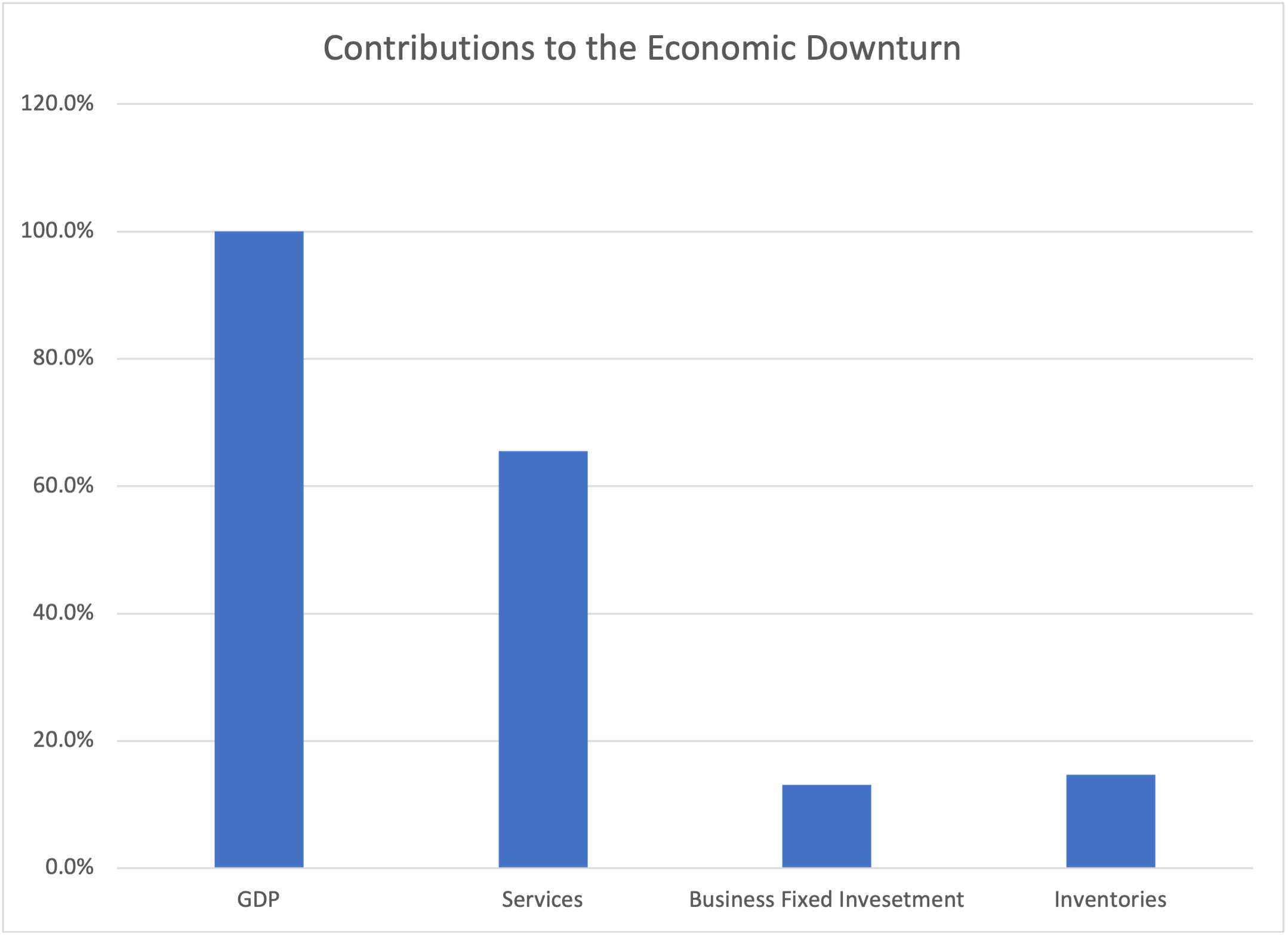

The COVID-19 is a household spending event (“consumption” in the jargon of economics). Between Q4 of 2019 and the trough in Q2 2020, real gross domestic product (GDP) fell precipitously by $1,951.5 billion or 10.1 percent. As shown in the chart (below), 65.5 percent of that decline can be traced to reduced household spending on services. This follows directly from the threat of the virus: consumption of personal services such as restaurant meals, hotels, concerts, haircuts, and the like involved personal contact and ran the risk of infection with the coronavirus.

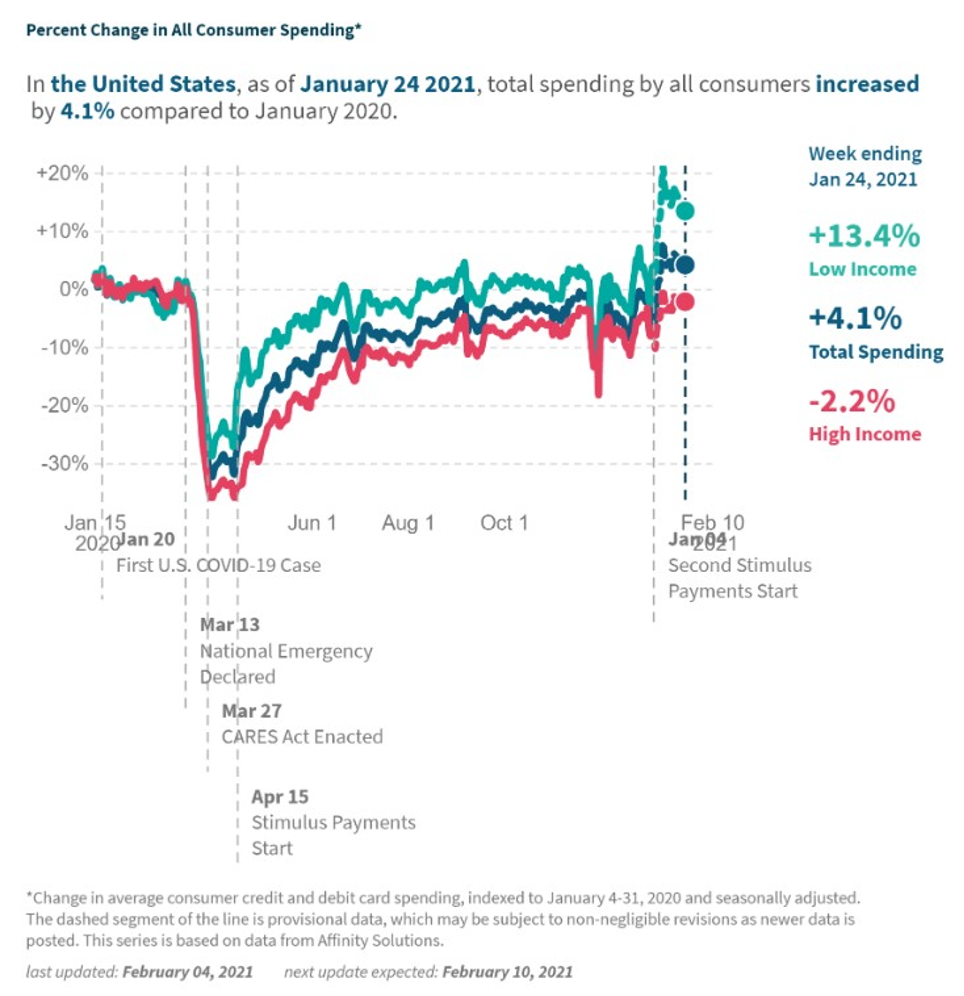

The impact of the virus’s threat is shown more clearly in the chart (below) reproduced from the Track the Recovery website. The chart displays a real-time estimate of total spending (blue), as well as spending by households in low-income (green) and high-income (red) zip codes. All three measures collapse in early March 2020. Of note, in part due to the large policy response, spending overall and in low-income areas is now above January 2020. Spending in high-income zip codes, however, has yet to recover and remains 2.2 percent below last year.

There are two lessons from these data. The first is that there is no real substitute for defeating the coronavirus. Only that will permit the full resumption of economic activity. Second, and as a corollary, none of the policies contemplated in the American Rescue Plan will stimulate the lost services spending of relatively affluent households.

The Near-term Outlook

Following the precipitous decline in early 2020, the economy began to recover and is expected to continue to do so. The chart, below, documents recent quarterly growth rates of GDP and reproduces the recent economic projections of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)[1]. The blue bars represent the quarter-by-quarter growth rates of GDP (at an annual rate), while the orange bars measure the “output gap” – the difference between the actual level of GDP and the potential for GDP when economic resources are fully employed – as a percentage of potential GDP.

The chart carries two lessons. The first is that the economy is growing and growing rapidly (over 5 percent in the current quarter). Clearly, the economy is far from recession territory and certainly not a disaster. As a consequence, the output gap will fall below 2 percent by the middle of this year and below 1 percent by the end of 2022.

As discussed earlier, the key headwind to the economy is the reduced spending due to the interference of the coronavirus. The lesson is that controlling and eliminating the virus is the only route to rapid, sustained, economy-wide growth. Policies that hasten this development should be a priority. In addition, Congress recently passed $900 billion in support of the economy. This constitutes roughly 4 percent of GDP. If the funds for checks, unemployment insurance (UI), the Paycheck Protection Program, and other funds move into the economy over the next 6 months, this is support at an annual rate of 8 percent.

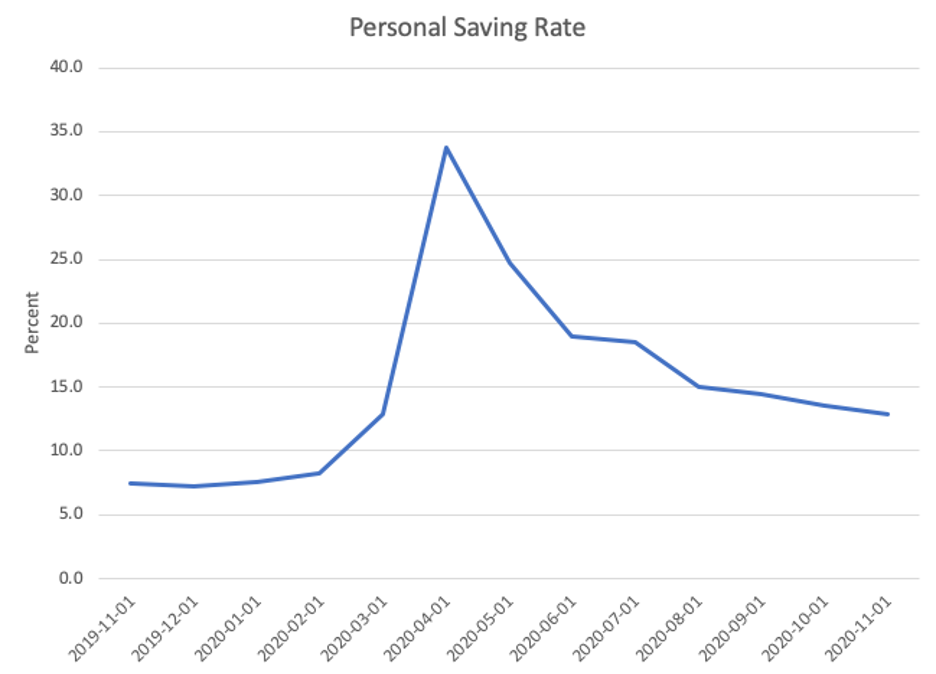

If recent history is any guide, much of these funds will be saved. Over the course of 2020, the saving rate skyrocketed from roughly 7.5 percent to nearly 35 percent in the aftermath of the CARES Act and remained nearly twice that through November.

The bottom line? The economy has underlying strength, and a lot of fiscal support remains in the pipeline. If the virus vanished overnight, there would be no case for further action.

The Theory of Economic Stimulus and Its Appropriate Application

The American Rescue Plan – the Biden Administration’s $1.9 trillion proposal – is advertised as much-needed stimulus to reverse the course of the economy and restore growth. As noted above, the economy is not in recession and is expected to grow. Moreover, recall that the “theory” of stimulus is that when the economy is below full employment, government stimulus—tax cuts, checks, spending—will boost spending. This will, in turn, stimulate business activity, which will begin a virtuous cycle of additional income to workers, more spending, and more hiring. Because of the virtuous cycle, $1 of stimulus is expected to have (much) more than a $1 impact—the “multiplier effect.”

That’s the theory; it just has nothing to do with the current policy debate. First, there will be no stimulus as long as the virus stops households from spending freely. Further, even taking the stimulus theory at face value, the $1.9 trillion size of the package eclipses the economic need. As noted above, currently, real GDP is below potential GDP with the output gap somewhere in the vicinity of $450 billion (in 2012 dollars). The $1.9 trillion proposal is a bit over $1.6 trillion in 2012 dollars. Thus, the proposal is a stimulus of over three times the size of the output gap that is needed to get the economy back to potential.

Based on any reasonable economic theory of stimulus, $1.9 trillion is far too large. In the chart (below), I assume that the stimulus hits the economy in equal increments over the 7 quarters from Q2 2021to Q4 2022. Moreover, I assume the “multiplier” impact of $1 of spending is a $0.50 increase in GDP – not much stimulus at all! As the chart indicates, the economy exceeds its potential by the final quarter of this year. From that point forward, the only result will be overheating that will lead to inflated asset prices, inflated prices for goods and services, and an increased risk of economic turmoil.

There is an alternative way to look at these efforts: as “relief” that replaces income to relieve the burden of the crisis, with no pretense that there will be “stimulus.” From that perspective, the funds should be targeted on those in financial distress, but the latest proposal is far too broad. The request to send checks includes individuals even if they did not miss a day of work or a single paycheck. It would be better to target the long-term unemployed. Labor Department data indicate that nearly four million people have been unemployed for 27 weeks or longer. They each could receive a check for over $96,000 with only a fraction of the same pool of money. While that’s not realistic, $2,000 more to the long-term unemployed would cost only $8 billion.

The Composition of the Plan

The second key aspect of the proposal is that its content has an internal contradiction. In broad terms, there are provisions to fight the coronavirus with more vaccines and testing, more than $1 trillion for households, and $440 billion for aid to communities and businesses. If the plans to fight the virus are successful, however, there will be no need for special monies to open schools, open child daycares, provide paid leave, support businesses, or stimulate household spending. Only if the vaccination plan is expected to fail does it make sense to provide large-scale support for the economy through the summer and into the fall. The sensible strategy is to robustly fund the Biden vaccination plan, check for success, and continue to take the pulse of the economy.

The third key feature is that some of the economics are very weak (at best). It makes no sense to increase to $400 the supplemental UI benefit. Setting the benefit at $300 was a tough compromise; there is the potential for great damage in raising it to $400. At the $400 level, 50 percent of workers nationwide may be able to make more on unemployment than at work, which can create a strong disincentive for them to return to work. Similarly, there is no rationale for extending the UI to the end of September (especially if one expects the labor market to be essentially unimpaired by the virus during the summer).

Consider also the proposal to spend $40 billion on housing programs, which broadly includes $25 billion for rental assistance, $10 billion for homeowner assistance, and $5 billion for homelessness assistance.[2],[3] Conceptually, I find it difficult to reconcile the need for specific assistance on housing with the notion that Congress has provided hundreds of billions in stimulus checks and enhanced UI benefits to permit households to maintain their budgets – including rent and mortgages. Moreover, the funding is not temporary; it would be available to be disbursed for up to 5 years (until September 30, 2025); well past the expected duration of the COVID pandemic.[4]

This request comes on top of $40 billion already provided for housing programs in response to COVID,[5] including $25 billion in temporary emergency rental assistance funds Congress just provided in the $900B spending bill that became law in late December.[6] A total of $80 billion seems out of line with the actual need. The National Multifamily Housing Counsel’s (NMHC) rent payment tracker has consistently shown from April 2020 through Jan. 2021 that by the 20th of the month 8-11 percent of renting households have not paid their rent and that by the end of the month 5-7 percent of renting households have not paid their rent.[7] Using the upper end of those ranges puts the price tag in the neighborhood of the National Council of State Housing Agencies that estimated renting households could owe $13-24B in unpaid rent by Jan. 2021.[8]

Another questionable design is the checks to households. The $600 checks provided in December will produce no real stimulus; raising them to $2,000 doubles down on a failed policy. If the checks are, instead, viewed as relief for those facing financial travail they need to be targeted on the long-term unemployed.

Raising the minimum wage to $15 per hour is the antithesis of “stimulus” and should therefore be excluded from the package. CBO’s recent study finds that the proposed legislation would raise the number of unemployed by 1.4 million. Jobs would decline because “From 2021 to 2031, the cumulative pay of affected people would increase, on net, by $333 billion.” Also, “That net increase would result from higher pay ($509 billion) for people who were employed at higher hourly wages under the bill, offset by lower pay ($175 billion) because of reduced employment under the bill.”

To date, the fiscal response to COVID-19 has been appropriately large, timely, and entirely temporary. The final thing to note is that many of these proposals have nothing to do with COVID-19 and are permanent or clearly intended to be: the grotesque bailout of the multiemployer pension system, as well as the expanded and advanceable child tax credit, the childcare tax credit, the expanded earned income tax credit, and the expanded and larger premium tax credits.

The bottom line is that the Biden American Rescue Plan is inconsistent with the current and projected strength of the economy, ignores economic support that is in the pipeline, spends over a trillion on problems that the vaccination program is intended to solve, and contains numerous extraneous proposals. Any legislative compromise that will pass Congress should have to be much better designed.

Thank you, and I look forward to your questions.

[1] I adjusted the CBO projection because the actual GDP for the fourth quarter of 2020 is below the CBO projection. I raised the growth rates of GDP in the first half of 2021 to reach the projected level in Q3 of 2021.

[2] https://docs.house.gov/meetings/BA/BA00/20210210/111179/HMTG-117-BA00-20210210-SD002.pdf

[3] https://docs.house.gov/meetings/BA/BA00/20210210/111179/HMTG-117-BA00-20210210-SD002.pdf

[4] Sections 4201(j), Section 4207(a), Section 4206(a) of HFSC reconciliation bill, available at https://docs.house.gov/meetings/BA/BA00/20210210/111179/HMTG-117-BA00-20210210-SD003.pdf

[5] https://www.covidmoneytracker.org/

[6] https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/cares/emergency-rental-assistance-program

[7] https://www.nmhc.org/research-insight/nmhc-rent-payment-tracker/; https://www.nmhc.org/globalassets/research–insight/rent-payment-tracker/data-downloads/rent-payment-tracker-02092021.xlsx

[8] https://www.ncsha.org/resource/stout-rental-and-eviction-live-data/