Solution

December 7, 2017

A Menu of Options to Grow the Labor Force

Executive Summary

During the Great Recession and ensuing recovery, United States labor force participation declined substantially. While much of the decline is due to aging and retirement, labor force participation is also lagging among those ages 25 to 54 (commonly referred to as prime-age individuals). The labor force participation rate of prime-age men has been declining since 1953 and the participation rate of prime-age women has been stagnant since 1990.

This study explores a range of public policy options to increase labor force participation. These include pro-work safety net reforms and other reforms that would reduce barriers to entering the workforce.

Pro-Work Safety Net Reforms

- Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit for childless adults;

- Introduce work requirements to Medicaid;

- Reform disability insurance;

- Add work requirements and skills development programs to child support enforcement, food stamps, and housing assistance.

Other Options

- Repeal the Affordable Care Act;

- Expand access to paid family leave;

- Reduce opioid dependency;

- Reform the criminal justice system;

- Improve workforce training.

These reforms would eliminate major work disincentives, improve job continuity, prepare workers for the jobs that employers demand, and spur economic growth.

Introduction

One of the largest challenges facing the U.S. economy is declining labor force participation. The labor force participation rate represents the portion of noninstitutionalized adults who are either employed or looking for work. Since the beginning of the Great Recession, the labor force participation rate has steadily declined from 66.0 percent in December 2007 to 62.7 percent as of November 2017. Yet, underlying this decline are even more troubling trends: Labor force participation among prime-age men (ages 25 to 54) has been declining since the 1950s, and it has stagnated among prime-age women since the 1990s. Both of these trends are problems for the U.S. economy because prime-age individuals are among the most skilled and productive workers in the labor force.

Fortunately, there are ways to boost workers’ participation in the economy. This paper discusses a range of options policymakers can pursue to increase labor force participation among prime-age workers.

Labor Force Participation: Recent and Historic Trends

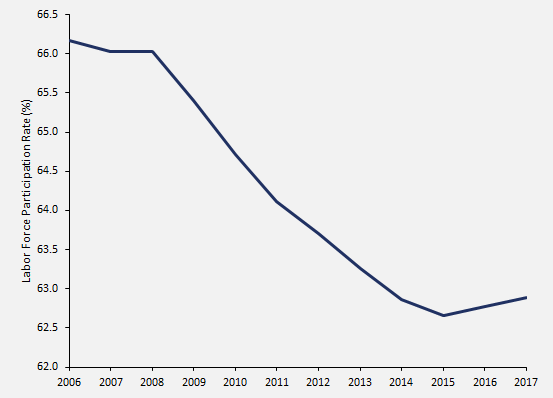

During the Great Recession, the United States’ labor force participation rate plummeted. Chart 1 contains the labor force participation rate from 2006 to 2017.

Chart 1: Civilian Labor Force Participation Rate[1]

At the start of the recession in December 2007, 66.0 percent of the civilian noninstitutional population was in the labor force, meaning 66.0 percent were either employed or looking for work.[2] By 2015, the rate had fallen to 62.5 percent, where it has hovered ever since. In November 2017, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) recorded a labor force participation rate of 62.7 percent.

One of the major reasons for this decline is population aging. Baby boomers make up a substantial portion of the labor force, but are now in their 50s and 60s and beginning to retire. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, retirement accounts for roughly 75 percent of the total decline in labor force participation since 2007.[3] However, it is no coincidence that the labor force participation rate began declining at the start of the Great Recession. During the recession, millions of Americans were unemployed for long periods of time and many gave up looking for work, deciding instead to retire early, go back to school, or simply exit the labor force and remain jobless.

Longer-term trends are also underlying the recent decline. Specifically, the labor force participation rate among prime-age workers (ages 25 to 54) has been declining for men and has been stagnant for women. This is problematic for the U.S. economy because prime-age individuals are the most likely to be working and are the most productive workers in the labor force. Without them, not only does the country lose an important source of labor, but an important source of skilled labor.

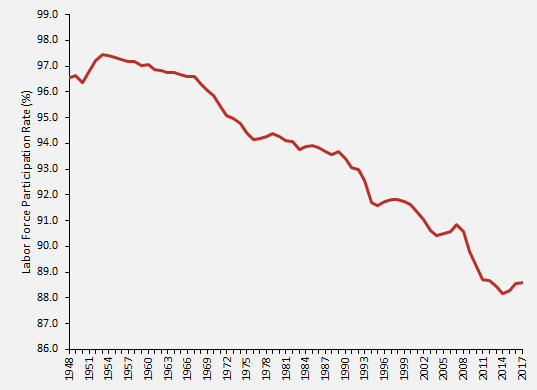

Chart 2 contains the labor force participation rate of prime-age men since 1948.

Chart 2: Prime-Age Male Labor Force Participation Rate (Ages 25 to 54)[4]

After peaking in the 1950s, the prime-age male labor force participation rate has steadily declined. According to the BLS, 97.5 percent of all prime-age males were either employed or looking for work in 1953. As of 2017, 88.6 percent of men are in the labor force, an 8.9 percentage point decline. Although prime-age men remain much more likely than the rest of the population to be in the labor force, the long-term decline is worrisome.

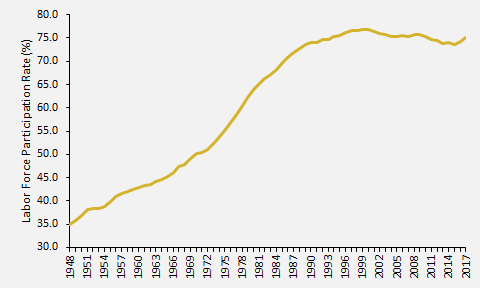

In the meantime, the labor force participation rate of prime-age women surged throughout the second half of the 20th century before plateauing in the 1990s. Chart 3 contains the labor force participation rate of prime-age women.

Chart 3: Prime-Age Female Labor Force Participation Rate (Ages 25 to 54)[5]

The labor force participation rate for prime-age women rose from 34.9 percent in 1948 to 74.0 percent in 1990. Since then, the rate has stagnated for almost three decades, hovering between 73.7 percent and 76.8 percent. While women are not necessarily leaving the labor force, the current decades-long stagnation means that women are not offsetting any of the losses from men ceasing to work.

The decline in labor force participation poses serious challenges to the U.S. economy, as a robust labor supply is vital to economic growth. One potential result of this decline is that companies have struggled to hire. Currently, the United States has roughly 6.1 million job openings, which is the most on record and indicates that companies are growing and looking for workers, typically a sign of economic health.[6] Nevertheless, the fact that the number of openings continues to rise, well after the end of the Great Recession, could indicate that the decline in labor force participation is restricting businesses’ growth and ability to add workers. Meanwhile, the U.S. economy has been stuck at a mediocre 2 percent growth rate, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that economic growth will not improve for the foreseeable future.[7] In order to break out of this anemic growth environment, policymakers need to find a way to increase the labor supply.

The good news is that there are a range of policy options to get workers, particularly prime-age workers, back into the labor force. In the following, this report examines safety net reforms and other ways policymakers can increase the labor force participation rate.

Pro-Work Safety Net Reforms

Reforming the social safety net with pro-work changes would not only improve the government’s anti-poverty efforts, but it would also increase labor force participation. Previously, American Action Forum (AAF) research examined how the government’s safety net programs have impacted poverty.[8] It found that while the government has alleviated suffering by providing millions of families enough assistance to avoid poverty, it has failed to give them the tools they need to escape poverty on their own. The best tool to escape poverty is work. Thus, pro-work safety net reforms would not only increase labor force participation, but also reduce poverty. In particular, policymakers could expand the Earned Income Tax Credit for childless adults, introduce work requirements to Medicaid, and reform disability insurance, among other reforms.

1. Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit for Childless Adults

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) subsidizes the pay of low-income working families through the tax code. The value of the credit is a fixed percentage of family earnings; as earnings increase, so does the credit at a constant rate determined by the number of children. The value of the credit peaks once a family’s income reaches a certain range, also determined by the number of children. Once earnings rise above that range, the credit reduces at a constant rate until a family no longer qualifies for the EITC. The EITC is fully refundable, meaning that if the credit exceeds a family’s tax liability, the family still receives the full amount of the credit, with the excess coming as a tax refund.[9]

The EITC is an effective anti-poverty program because it is well targeted to low-income families and, more importantly, encourages them to work. By design, in order to receive the EITC, a family must have earned income. Thus, only those with jobs receive the benefit. The EITC has been credited with directly keeping 6.5 million people out of poverty in 2015.[10] But by encouraging work and placing recipients on a path to self-sufficiency, the benefit has an even greater impact than the immediate assistance suggests. A study by Michael Kean and Robert Moffitt found that expansions in the EITC between 1984 and 1996 were associated with a 10.37 percentage point increase in the labor force participation rate.[11]

Despite its strengths, the EITC falls short when it comes to helping those without children. While the maximum credit for an adult with one child is $3,400, the maximum credit for an adult with no children is only $510.[12] As a result, childless adults in poverty currently do not receive comparable assistance from the EITC, and childless adults currently not working do not receive the same incentives to enter the labor force. So, one policy option that would both assist those in poverty and raise labor force participation is to expand the EITC for childless adults.

A previous AAF study[13] examined the effects of then-Chairman of the House Budget Committee Paul Ryan’s proposal to expand the EITC for childless adults,[14] which was almost identical to the proposal from former President Barack Obama.[15] The proposal would lower the EITC’s age limit from 25 to 21 so more young adults could receive the benefit, double the maximum credit available to childless adults, and expand the income range in which childless adults would be eligible for the credit. The study found that the proposal would increase the number of childless adults who are immediately eligible for the EITC by 5.2 million. The number of childless adults the program would keep out of poverty would increase from 20,300 to 110,100. This would be particularly helpful to men because non-custodial parents are primarily men and are often only eligible for the childless EITC.

Most important, the policy would result in a profound increase in employment. A 2007 study found that a 10-percent increase in the EITC’s maximum credit is associated with a 1.0 to 1.5 percent increase in employment among single mothers.[16] Applying this estimate to the proposed EITC expansion, AAF’s study found that employment among childless adults would increase by 10 percent, meaning that 8.3 million individuals would enter the labor force and find employment.

2. Introduce Work Requirements to Medicaid

Work requirements in safety net programs have a highly effective track record, and Medicaid is well-suited to incorporate them.[17] After lawmakers created Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) in the 1990s and introduced work requirements to welfare, the labor force participation rates of single mothers rose and the poverty rates of single mothers and children both fell substantially.[18] Moreover, as previously highlighted, the EITC is successful because it also has a work requirement: in order to receive the benefit, families must have earned income.

Requiring able-bodied, adult Medicaid recipients to work would bring many individuals to the labor force without greatly disrupting the program. A report from the Kaiser Family Foundation reveals that just over 1 million non-elderly, non-disabled people would be impacted by work requirements because they do not work and do not have a good reason to be jobless.[19] Consequently, if Congress were to introduce work requirements to Medicaid, over 1 million people would need to find a job, search for a job, or participate in work-related activities in order to remain covered. Introducing work requirements to Medicaid would bring the successful qualities of TANF and the EITC to this health care benefit by encouraging many able-bodied adults to enter the labor force.[20] If all 1 million of these Medicaid recipients were to enter the labor force, then the current labor force participation rate would increase from 62.7 percent to 63.1 percent.

3. Reform Disability Insurance

There is broad consensus that the nation’s disability programs are, in part, leading to the decline in labor force participation among younger workers, particularly prime-age men.[21] The portion of prime-age men on disability insurance rose from 1 percent to 3 percent between 1967 and 2014. During the same period, the portion of prime-age men in the labor force fell by 7.5 percentage points. This suggests that disability insurance could account for a quarter of the decline in labor force participation among prime-age men.[22], [23]

The growth in disability insurance is likely not due to a substantial increase in permanent disabilities or ailments. Evidence suggests that instances of work-limiting disabilities have remained fairly constant over the past several decades. One study found that 7.3 percent of the working-age population reported a work-limiting disability in 1981. In 2010, 7.8 percent of working-age adults reported a disability, only a small increase.[24] According to the Centers for Disease Control, the portion of adults with at least one disability decreased slightly between 1997 and 2014.[25] Moreover, since the government established disability insurance in the 1950s, physically intensive labor has become much more infrequent, meaning that work has become much less likely to cause physical disabilities and much more able to accommodate physical disabilities.[26] Together, these factors would lead one to expect disability insurance rolls to decline, instead of rise. While a portion of the rise in disability insurance rolls may be tied to increased incidences of mental disabilities and improved diagnosis capabilities, the program is also likely growing because many work-able people are receiving disability benefits. The latter is a major problem for the labor force because disability insurance has strong work disincentives. In order to receive disability insurance, participants must show, for an extended period of time, that they are unable to work. Once they are on disability insurance, they must keep earnings low or they will lose the benefit.[27]

Researchers have found that the growth in disability insurance is tied to an applicant screening process that is based on the physically intensive labor force of the 1950s, not the modern work environment.[28] The growth is also linked to an increase in the program’s benefits relative to the benefits available in other public assistance programs.[29] Reforms that prevent able-bodied individuals from enrolling in disability insurance (without overburdening those who are legitimately disabled), and encourage able-bodied adults who are currently receiving benefits to seek employment could help increase labor force participation.[30]

4. Add Work Requirements to Other Safety Net Programs

The federal government effectively reduces material deprivation, but does not reduce poverty because it has failed to increase self-sufficiency.[31] Thus, it is vital that policymakers encourage low-income people to work at every opportunity. In Speaker Paul Ryan’s blueprint to combat poverty, his task force highlighted a series of other reforms that intend to do just that.[32] For instance, while the TANF work requirements have been highly effective, states have allowed many benefit recipients to not work. The federal government could strengthen TANF’s work requirements by mandating that states have more healthy recipients engage in work or work-related activities. In addition, work requirements and skills development programs could be attached to child-support enforcement, food stamps, and housing assistance.[33]

Other Options to Increase Labor Force Participation

5. Repeal the Affordable Care Act

Evidence suggests that the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has caused labor force participation to decline significantly.[34] With the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and premium subsidies, many low-income Americans no longer need to work in order to obtain health insurance. Moreover, these benefits impose an implicit high marginal tax on low-income individuals who would lose the benefit if they earn too much money. This is a bad combination as the ACA creates significant incentives to leave the labor force. Consequently, the CBO estimates that repealing the ACA would increase labor force participation by between 0.8 percent and 0.9 percent,[35] which equals an additional 2 million full-time-equivalent workers. This increase would in turn increase economic output by 0.7 percent.[36]

6. Expand Access to Paid Family Leave

The United States is the only developed country in the world without a public policy for paid family leave.[37] Yet, a federal policy that increases access to paid family leave could help increase labor force participation, primarily among prime-age women.[38] Research shows that paid family leave in reasonable amounts can lead to higher employment rates.[39] Workers with the benefit are much less likely to quit their jobs due to family reasons, ensuring greater job continuity and labor force attachment. These positive employment effects are particularly apparent for mothers.[40]

Paid family leave has many labor force benefits, but that does not mean the United States should adopt a massive new universal program, like the one proposed in the Family and Medical Insurance Leave (FAMILY) Act.[41] The FAMILY Act would cost the federal government at least $85.9 billion by providing paid family leave to the entire workforce.[42] Since two-thirds of workers who take family leave are already paid by their employers, a universal approach like the FAMILY Act would be unnecessary and redundant.[43] In contrast, policies that either incentivize businesses to increase their paid family leave benefits or help workers afford time away from work through tax-advantaged savings accounts would help many middle-income workers take family leave. Those types of solutions would not help as many low-income workers, however, as they are the least likely to have any paid leave benefits and the least able to save on their own. Thus, a government program that specifically targets low-income workers would be the most efficient and direct way to expand access to paid family leave.[44]

7. Reduce Opioid Dependency

The United States’ growing opioid crisis is also hampering workforce participation. Between 1999 and 2015, prescription opioid sales per capita rose 356 percent. Opioid-related deaths have quadrupled during that time frame.[45] People commonly become addicted to opioid medication when it is prescribed by a doctor. Once the prescription expires, many turn to more powerful and dangerous illegal opioids, such as heroin. In 2016, 64,000 people died from drug overdoses, which is about 20 percent higher than in 2015. The increase was largely driven by legal prescription opioids and illegal opioids like heroin and non-prescription fentanyl.[46]

While the health problems associated with the opioid crisis are glaring, the economic consequences are also substantial. Opioid drug use is among the leading causes of the decline in labor force participation for prime-age workers. Close to half of all prime-age men not in the labor force take pain medication daily. Two-thirds of the men who take pain medication daily use prescription medicine.[47] Alan Krueger suggested in a study this year that the increase in opioid drug use could account for 20 percent of the decline in the male labor force participation rate and 25 percent of the decline in the female labor force participation rate between 1999 and 2015. Moreover, these trends are not just limited to the manufacturing sector, where workers are more likely to get work-related injuries and end up on prescription strength painkillers in the first place. Rather, opioid drug use and its toll on the labor force are widespread throughout the economy.[48]

Thus, one way to raise the labor force participation rate is to reduce worker dependency on opioids. To tackle this issue, policymakers could work to limit opioid prescriptions, which has been among the most common ways people become addicted. Policymakers could also improve the accessibility of anti-overdose drugs, improve the nation’s rehab systems, and work to stop the entry of illegal opioids into the country.[49]

8. Reform the Criminal Justice System

Policymakers from both sides of the aisle are beginning to call for criminal justice reform and a reduction in incarceration. While crime in America occurs at roughly the same rate as it did 50 years ago, incarceration rates have increased fivefold. By 2008, there were between 12.3 million and 13.9 million ex-felons in America, individuals who have a particularly difficult time joining and staying connected to the labor force.[50] Research suggests that previous incarceration accounted for over half of the decline in the labor force participation rate among young adult black men without a high school degree between 1979 and 2000.[51] Incarceration has been shown to reduce the number of weeks worked in a year by 6 to 11. Moreover, incarceration deteriorates human capital by reducing chances that individuals gain more education and job experience. Those who were previously incarcerated also lose significant portions of their social networks, which adds to the difficulty of finding work.[52]

By reducing incarceration, criminal justice reform could raise labor force participation, particularly among prime-age men. Some have argued that prolonged pretrial detention in local jails is harmful to defendants because it increases the likelihood of accepting a plea deal from prosecutors. Pretrial detention also stigmatizes the defendants’ defense in trial, as the courts have already deemed them not trustworthy enough to attend court appointments on their own or to avoid more criminal behavior. Policymakers could adjust the initial phase of the criminal justice system so that local jails begin to hold defendants who are actually dangerous or pose a flight risk, rather than just low-income defendants who are unable to afford bond.[53] Policymakers could also improve support systems for previously incarcerated adults and help them transition into the labor force.[54] And, to reduce recidivism, policymakers could make education programs more broadly available for the incarcerated.[55]

9. Improve Workforce Training

Over the past few decades, globalization, trade, and technological advancements have grown the economy, improved quality of life, and created jobs. These developments have also significantly changed the skills that employers demand. Many workers, however, are unprepared for these new types of jobs. As a result, when a manufacturer shuts down a plant, for example, its workers are often unable to adjust to the types of positions that employers are currently looking to fill. Many believe that some workers are exiting the labor force because they are discouraged by the mismatch between their skills and the skills employers demand, and the low wages of the jobs they can obtain.[56]

To increase labor force participation, policymakers could explore ways to encourage lifelong learning among younger workers and skills acquisition for workers in the middle of their careers. These types of policies could take the form of “worker training accounts” or “lifelong learning accounts,” which would provide workers the flexibility to save on their own and use federal assistance in a way that best prepares them for available jobs.[57] Policymakers could also improve coordination between schools and employers, increase access to career advisers, and improve the federal apprenticeship system so that it better prepares individuals for jobs that employers are increasingly demanding (instead of for those that are disappearing).[58]

Conclusion

The declining labor force participation rate is a phenomenon that could threaten long-term economic growth in the United States. Particularly problematic is the long-term stagnation in the labor force participation rate of prime-age female workers and the over half century decline in the prime-age male participation rate. Fortunately, policymakers have a number of options to help combat this trend. If successful, these efforts will not only encourage more people to work—they will also spur much-needed economic growth.

Updated December 8, 2017 to reflect November 2017 labor force estimates.

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, https://www.bls.gov/data/.

[2] All labor force statistics are of the civilian noninstitutional population, which includes everyone 16 and older who do not live in institutions (such as prisons, long-term care hospitals, and nursing homes) and are not on activity duty in the military.

[3] “Labor Force Participation Dynamics,” Center for Human Capital Studies, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, updated November 13, 2017, https://www.frbatlanta.org/chcs/labor-force-participation-dynamics.aspx.

[4] Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey, https://www.bls.gov/data/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/jlt/.

[7] “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027,” Congressional Budget Office, June 29, 2017, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52801.

[8] Ben Gitis & Curtis Arndt, “Material Well-Being vs. Self-Sufficiency: How Adjusting Poverty Measures Can Reveal a Diverging Trend in America,” American Action Forum, March 9, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/material-well-vs-self-sufficiency-adjusting-poverty-measurements-can-reveal-diverging-trend-america/.

[9] “What is the earned income tax credit (EITC)?” The Tax Policy Center, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-earned-income-tax-credit-eitc.

[10] “Policy Basics: The Earned Income Tax Credit,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 21, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/policy-basics-the-earned-income-tax-credit.

[11] Keane, Michael, and Robert Moffitt, “A structural model of multiple welfare program participation and labor supply,” International Economic Review Vol. 39, No. 3, August 1998, pp.553-589, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2527390?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

[12] “What is the earned income tax credit (EITC)?” The Tax Policy Center, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-earned-income-tax-credit-eitc.

[13] Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Ben Gitis, & Curtis Arndt, “The Work and Safety Net Effects of Expanding the Childless EITC,” American Action Forum, February 2, 2016, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-work-and-safety-net-effects-of-expanding-the-childless-eitc/.

[14] Paul Ryan, “Expanding Opportunity in America,” House Budget Committee, July 2014, http://budget.house.gov/uploadedfiles/expanding_opportunity_in_america.pdf

[15] “The President’s Proposal to Expand the Earned Income Tax Credit,” Executive Office of the President and U.S. Treasury Department, March 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/eitc_report_0.pdf.

[16] Joseph J. Sabia, “The Impact of Minimum Wage Increases on Single Mothers,” Employment Policies Institute, August 2007, https://www.epionline.org/studies/r109/.

[17] Ben Gitis & Tara O’Neill Hayes, “The Value of Introducing Work Requirements to Medicaid,” American Action Forum, May 2, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/value-introducing-work-requirements-medicaid/.

[18] Ben Gitis & Curtis Arndt, “The 20th Anniversary of Welfare Reform,” American Action Forum, August 22, 2016, https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/20th-anniversary-welfare-reform/.

[19] “Rachel Garfield, Robin Rudowitz, and Anthony Damico, “Understanding the Intersection of Medicaid and Work,” The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, February 15, 2017, http://kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/understanding-the-intersection-of-medicaid-and-work/.

[20] Ben Gitis & Tara O’Neill Hayes, “The Value of Introducing Work Requirements to Medicaid,” American Action Forum, May 2, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/value-introducing-work-requirements-medicaid/.

[21] The two federal disability insurance programs are Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) and Supplemental Security Insurance (SSI).

[22] Alan B. Krueger, “Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, September 7-8, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/1_krueger.pdf.

[23] “The Labor Force Participation Rate Since 2007: Causes and Policy Implications,” Council of Economic Advisers, Executive Office of the President of the United States, July 2014, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/labor_force_participation_report.pdf.

[24] Richard V. Burkhauser & Mary C. Daly, “The Declining Work and Welfare of People with Disabilities: What Went Wrong and a Strategy for Change,” Introduction, AEI Press, 2011, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/labor/aging/rsi/rsi_papers/2011/Burkhauser1.pdf.

[25] “Health, United States, 2015,” National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, June 22, 2017, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/hus15.pdf.

[26] Mark J. Warshawsky & Ross A. Marchand, “Modernizing the SSDI Eligibility Criteria: A Reform Proposal That Eliminates the Outdated Medical-Vocational Grid,” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, April 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Warshawsky-SSDI-Eligibility-Criteria.pdf.

[27] Brent Orrell, Harry J. Holzer, & Robert Doar, “Getting men back to work: Solutions from the right and left,” American Enterprise Institute, April 20, 2017, http://www.aei.org/publication/getting-men-back-to-work-solutions-from-the-right-and-left/.

[28] Mark J. Warshawsky & Ross A. Marchand, “Modernizing the SSDI Eligibility Criteria: A Reform Proposal That Eliminates the Outdated Medical-Vocational Grid,” Mercatus Working Paper, Mercatus Center, George Mason University, April 2015, https://www.mercatus.org/system/files/Warshawsky-SSDI-Eligibility-Criteria.pdf.

[29] Richard V. Burkhauser & Mary C. Daly, “The Declining Work and Welfare of People with Disabilities: What Went Wrong and a Strategy for Change,” Introduction, AEI Press, 2011, https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/www/external/labor/aging/rsi/rsi_papers/2011/Burkhauser1.pdf.

[30] Brent Orrell, Harry J. Holzer, & Robert Doar, “Getting men back to work: Solutions from the right and left,” American Enterprise Institute, April 20, 2017, http://www.aei.org/publication/getting-men-back-to-work-solutions-from-the-right-and-left/.

[31] Ben Gitis & Curtis Arndt, “Material Well-Being vs. Self-Sufficiency: How Adjusting Poverty Measures Can Reveal a Diverging Trend in America,” American Action Forum, March 9, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/material-well-vs-self-sufficiency-adjusting-poverty-measurements-can-reveal-diverging-trend-america/.

[32] “Poverty, Opportunity, and Upward Mobility,” A Better Way, House Speaker’s Office, June 7, 2016, https://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Poverty-PolicyPaper.pdf.

[33] Ben Gitis, “The Speaker’s Blueprint to Fight Poverty,” American Action Forum, June 8, 2016, https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/speakers-blueprint-fight-poverty/.

[34] Ben Gitis, “Obamacare and the Labor Market,” American Action Forum, May 2, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/obamacare-labor-market/.

[35] Edward Harris & Shannon Mok, “How CBO Estimates the Effects of the Affordable Care Act on the Labor Market,” Working Paper 2015-09, Congressional Budget Office, December 2015, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/workingpaper/51065-acalabormarketeffectswp.pdf.

[36] “Budgetary and Economic Effects of Repealing the Affordable Care Act,” Congressional Budget Office, June 2015, https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/50252-effectsofacarepeal.pdf.

[37] Gretchen Livingston, “Among 41 Nations, U.S. Is the Outlier When It Comes to Paid Parental Leave,” Pew Research Center, September 26, 2016, http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/09/26/u-s-lacks-mandated-paid-parental-leave/.

[38] Ben Gitis & Angela Rachidi, “Affordable and Targeted: How Paid Parental Leave in the US Could Work,” American Action Forum & American Enterprise Institute, March 29, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/solution/affordable-targeted-paid-parental-leave-us-work/.

[39] Maya Rossin-Slater, “Maternity and Family Leave Policies,” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2017, http://www.nber.org/papers/w23069.

[40] Jochen Kluve and Sebastian Schmitz, “Social Norms and Mothers’ Labor Market Attachment: The Medium-Run Effects of Parental Benefits,” Institute for the Study of Labor, April 2014, http://ftp.iza.org/dp8115.pdf; and Heather Boushey, “To Grow Our Economy, Start with Paid Leave,” Cato Institute, https://www.cato.org/publications/cato-online-forum/grow-our-economy-start-paid-leave.

[41] “Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act,” S.337, 115th Congress, 2017, https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/337.

[42] Ben Gitis, “The Earned Income Leave Benefit: Rethinking Paid Family Leave for Low-Income Workers,” American Action Forum, August 15, 2016, https://www.americanactionforum.org/solution/earned-income-leave-benefit-rethinking-paid-family-leave-low-income-workers/.

[43] Ben Gitis, “What Pew’s Report on Paid Leave Preferences Means for Policy,” American Action Forum, April 19, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/pews-report-paid-leave-preferences-mean-policy/.

[44] Ben Gitis, “The Earned Income Leave Benefit: Rethinking Paid Family Leave for Low-Income Workers,” American Action Forum, August 15, 2016, https://www.americanactionforum.org/solution/earned-income-leave-benefit-rethinking-paid-family-leave-low-income-workers/.

[45] Alan B. Krueger, “Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, September 7-8, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/1_krueger.pdf.

[46] Josh Katz, “The First Count of Fentanyl Deaths in 2016: Up 540% in Three Years,” The Upshot, The New York Times, September 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/02/upshot/fentanyl-drug-overdose-deaths.html.

[47] Alan B. Krueger, “Where Have All the Workers Gone? An Inquiry into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation Rate,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, September 7-8, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/1_krueger.pdf.

[48] Ibid.

[49] “The Federal Response to the Opioid Crisis,” Full Committee Hearing, U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, & Pensions, October 5, 2017, https://www.help.senate.gov/hearings/the-federal-response-to-the-opioid-crisis.

[50] John Schmitt & Kris Warner, “Ex-offenders and the Labor Market,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, November 2010, http://cepr.net/documents/publications/ex-offenders-2010-11.pdf.

[51] Eleanor Krause & Isabel Sawhill, “What We Know and Don’t Know About Declining Labor Force Participation: A Review,” The Brookings Institution, May 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/ccf_20170517_declining_labor_force_participation_sawhill1.pdf.

[52] John Schmitt & Kris Warner, “Ex-offenders and the Labor Market,” Center for Economic and Policy Research, November 2010, http://cepr.net/documents/publications/ex-offenders-2010-11.pdf.

[53] Arthur L. Rizer, III, “The Conservative Case for Jail Reform,” National Affairs, Fall 2017, pp. 48-60, www.nationalaffairs.com.

[54] Brent Orrell, Harry J. Holzer, & Robert Doar, “Getting men back to work: Solutions from the right and left,” American Enterprise Institute, April 20, 2017, http://www.aei.org/publication/getting-men-back-to-work-solutions-from-the-right-and-left/.

[55] “Evidence-Based Public Policy Options to Reduce Future Prison Construction, Criminal Justice Costs, and Crime Rates,” Washington State Institute for Public Policy, October 2006, http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/952.

[56] Brent Orrell, Harry J. Holzer, & Robert Doar, “Getting men back to work: Solutions from the right and left,” American Enterprise Institute, April 20, 2017, http://www.aei.org/publication/getting-men-back-to-work-solutions-from-the-right-and-left/.

[57] For example, see http://www.wtb.wa.gov/lifelonglearningaccount.asp.

[58] Jacqueline Varas & Aaron Iovine, “The State of Federal Worker Training Programs,” American Action Forum, September 1, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/state-federal-worker-training-programs/.