Research

July 30, 2024

The False Promise of Rent Control

Executive Summary

- The Biden Administration has signaled support for a 5 percent national cap on annual rent increases that would impact nearly half of all rental units across the United States.

- Rent control is a blunt instrument that does not achieve its desired goal of lowering housing costs, benefitting only those in controlled housing at the expense of property value, future supply, quality, and every renter outside the program.

- A 5 percent cap on rent would not lower overall costs and could result in between $3,500 and $6,000 in additional costs for renters over a five-year period, alongside roughly $1 billion in administrative costs.

Introduction

Recently, President Biden announced a proposal to cap annual rent increases at 5 percent in an effort to ease the burden of rising housing costs. To enforce the cap, the administration would remove tax credits for impacted landlords who do not comply. The Biden Administration argues that it is only “cracking down on corporate landlords,” meaning those with more than 50 units– but that covers half the U.S. rental supply. [1] Such attempts at “rent- control” policies are not new, and are one area where most economists have a consensus view: Rent and other price controls do not achieve their intended goals, and lead to lower housing quality, reduced property values, more housing- supply shortages, higher administrative costs, reduced mobility, and no discernable impact on homelessness.[2]

Vice President Kamala Harris, the presumptive Democratic presidential nominee for the 2024 election, is likely to support this proposal. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Harris supported a bill that would prohibit landlords from raising rent, shutting off utilities, and reporting unpaid rent to credit companies.[3] Both average and median rent increases have been below 4 percent annually since 2005 and below 5 percent in the last decade, even including outlier events such as the pandemic.[4] In this case, a national rent growth cap of 5 percent will have virtually no impact on rising costs, though it may incentivize landlords to take this proposal as a green light to raise prices up to the 5 percent limit, thereby increasing costs in the long term. In either case, inefficiencies will arise, bureaucratic monitoring costs will go up, and the cost of renting could rise by between $3,500 and $6,000 for those in the program over the next 5-year period.

Realities of Rent Control

The history of rent control is littered with case studies, examples in which cities attempted to solve the problem of rising housing costs via top-down government restrictions. One such example is from San Francisco, where economic studies show the city’s rent controls reduced rental housing supply by 15 percent, led to city-wide rent increases of 5.1 percent, and limited overall housing turnover.[5] When rent control was eventually repealed in cities such as Cambridge, Massachusetts, property values increased by 45 percent, and it was discovered that $2 billion in costs had been placed on local property owners during the program.[6] Of these costs, 85 percent was imposed upon those outside rent-controlled apartments, further displaying the inequalities of a rent cap.

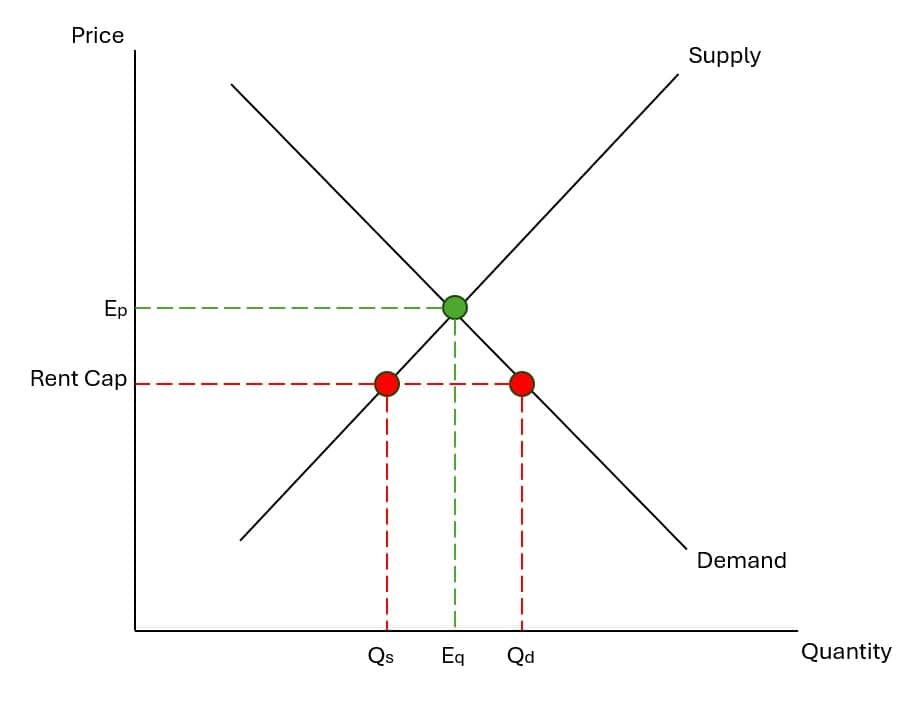

Figure 1: Housing Supply and Demand Graph

While Figure 1 can be found in most any introductory economics course, it displays the theoretical consequences of setting an arbitrary rent cap which do occur in the real world. With a price below the market equilibrium, the quantity of housing units demanded exceeds the quantity supplied, creating a shortage that would not have otherwise occurred. In fact, the quantity supplied of housing will decrease as some landlords no longer find it economically viable to rent out units or construct new ones. The only winners in this case are those lucky enough to get the artificially cheaper housing while many more are left behind.

Each side of the political aisle can find something to dislike about this policy measure. For one, there is rarely a way to target rent controls so that they benefit low-income individuals, with many instances where high-income earners can lock-in their now less-expensive apartment.[7] For another, there are significant spillover effects that reduce local property values as well as increased administrative costs to run the rent control program.[8] Moreover, a decrease in revenue would incentivize cost cutting in the form of reduced maintenance and housing unit quality.

What Causes Rent to Increase?

After the COVID-19 supply-chain shock, government lockdowns, and $5 trillion in U.S. stimulus spending, there has been historically high inflation.[9] Since 2020, the U.S. inflation rate has averaged roughly 5 percent compared to 2 percent between 2000 and 2019.[10] As would be expected, prices of most things rose, and substantially so, compared to the norm imbedded in public memory. During this three-year period, annual rents increased an average of approximately 7 percent (nearly double previous trends), while many locations saw double-digit rent hikes. Looking at state-by-state inflation and rent data in 2023, only 15 percent of the change in rent can be explained by increased costs relative to 2021.[11] One might expect that the substantial rent inflation might be partially a result of the Emergency Rental Assistance program’s $46 billion in rental support alongside thousands of dollars per person in direct payments to households and a moratorium placed upon evictions.[12]

Population: Another factor that appears to contribute to rising rent prices is population growth, as would be expected considering increased housing demand. Examining data for 47 states on rent and population growth between 2020 and 2021 indicates a 40 percent correlation.[13] Despite this somewhat significant corollary, regression analysis only shows that a little over 15 percent of the change in rent can be attributed to population growth.

Housing Units: One might expect there to be a reasonable relationship between the available supply of housing units and rent. This seems to be the case when examining 2022 and 2023 data on housing unit construction and changes in rent for 47 states. About 45 percent of the change in average rents in 2023 can be explained by the percent change in housing units (new construction) from 2022 to 2023.[14] This represents a negative 67 percent correlation between these two variables.

Income: A factor on which economic studies have focused is the influence income has on the price of rent within different localities. When examining the rent-control policies of New Jersey, multiple studies concluded that “median income, not the presence of rent control, is a stronger predictor of rents”.[15] On the national level, rent growth and wage growth are 25 percent correlated with one another but there is a lack of causality when comparing within the same year. Comparing rent growth in one year to the wage growth of the previous year paints a different picture, however. There is a 70 percent correlation between the rent in an observed year and the wage growth of the prior year, with 50 percent of rent growth attributable to prior-year wage growth.[16]

Figure 2: United States National Rent vs. Wage Inflation

Figure 3: United States National Rent vs. Prior Year Wage Inflation

Is Rising Rent a Concern?

For many in the United States, the rising cost of housing is a key concern relating to everyday economic security.[17] While average rent costs rose by roughly 7 percent annually during the COVID years, numerous cities across the country experienced rent increases of over 20 percent, far outpacing wage growth.[18] Thus, concerns surrounding rent likely depend heavily on whether one is located in a metropolitan area, how fast the population of that area is growing, and whether housing construction and wage growth are keeping pace.

Figure 4: Median Rent vs. Median Household Income Over Time

Taking a step back to look historically at the median rents and household incomes in the United States, we can see median rent has hovered at around 20 percent of median income.[19] The 2021-to-2023-timeframe can be characterized as a spike in rent in terms of percentage of income, much like between 2005 and 2010. Figure 4 gives a snapshot of rent in the United States as a whole but is not representative of every state or city, as high-demand locations with restricted housing supply will tend to have higher rents as a percentage of income. The upward trend is a concern.

Impact of a 5 Percent National Rent Cap

As over 50 percent of rental housing units would be impacted by the proposed 5 percent limit on annual rent growth, there would be dramatic national consequences. There are two possible scenarios that could play out. No matter which scenario occurs, historical case studies show that property values will be depressed, non-rent-controlled buildings will counteract controlled rents, there will be higher administrative costs, and quality housing supply will diminish. That this would only apply to larger landlords also creates an incentive to add an even larger number of small-scale renting operations to the market, which could induce rental unit sell-offs.

Scenario 1: Between 2005 and 2023, the median rate of annual rent growth was 3.95 percent and the average rate was 3.63 percent.[20] Excluding the pandemic years, the median rate of growth is the same and the average rate is closer to a flat 3 percent. This means that the arbitrary limit of 5 percent would not have an impact except in rental markets that are extreme outliers to national norms. These markets, which are already experiencing pressure due to migration, supply constraints, and other factors, would thus be made even worse off should the administration’s rent control policy take effect. Construction of additional rental apartments, as in other examples, would also decrease, thereby lowering long-term housing supply.[21]

Scenario 2: Alternatively, landlords might see the new rent cap as an opportunity to raise annual rents consistently at 5 percent since that is effectively their legal upper bound. There would be no real reason for landlords to charge below this threshold if they knew they would face zero ramifications below this barrier. In many ways, the Biden Administration’s proposal could act much like a tariff. When domestic manufacturers have a high price barrier between them and other countries, they can raise their prices up to the trade barrier since foreign companies can no longer compete at lower prices. Figure 4 demonstrates that if rent were to grow at 5 percent annually rather than the pre-pandemic median, the five-year cost to renters would amount to an additional $3,500. If compared to the pre-pandemic average rent growth, this would be an additional $6,000 over five years.

Both cases would have some sort of effect on property values, as other studies indicate that valuations often substantially rise once rent controls are removed.[22] As seen with the Cambridge, Massachusetts case, the ending of rent control raised property values by nearly $2 billion.[23] On a national scale, property values and by extension property taxes could depreciate to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars with the introduction of a rent-control policy.

Figure 5: Annual Rent Growth Projections With and Without Rent Control

One certain result of a national rent-control policy would be increased administrative costs, paperwork, and monitoring to ensure landlords are abiding by the rent cap. Estimating total costs is difficult without further plan details, yet some locales, such as Berkeley, California, finance their rent control program via a $250 fee placed on landlords.[24] This only applies to about 26,000 units, which means a national program would be over 750 times larger in scale.[25] Estimating the number of landlords impacted at roughly 550,000 out of about 24 million in the United States, that would mean annual administrative costs would be $140 million at a minimum.[26] This is likely a severe underestimate of the actual bureaucratic costs imposed, since other studies predict an administrative cost of $40 per housing unit, which would bring annual oversight costs to approximately $1 billion.[27]

Conclusion

Rent control does not achieve its intended goal of reducing costs. It devalues property, constrains housing supply, lowers quality, and increases administrative burdens. A 5 percent cap on rent would be no different. In a worst-case scenario, median rents would increase at a higher rate than historical trends. In effect, the United States would be paying $1 billion annually to raise renting costs up to $6,000 per renter at the same time national property values decrease by hundreds of billions of dollars. The only potential winners would be the lucky few able to lock into housing contracts in locations where annual rates typically increase by more than 5 percent. Meanwhile, everyone else would have to pay the price for this ineffective economic policy.

[1] FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Major New Actions to Lower Housing Costs by Limiting Rent Increases and Building More Homes | The White House

[2] Rent Control: Do Economists Agree? · Econ Journal Watch : Rent control, maintenance, housing availability, price ceiling, price control, vacancy allowance (econjwatch.org); Microsoft Word – Rent Control Literature Review Final 5 30 (nmhc.org); Why rent control won’t solve the issue of high rents in the U.S. (cnbc.com)

[3] Kamala Harris unveils housing plan as rent deadline looms – POLITICO

[4] Average Rent by Year [1940-2024 ]: Historical Rental Rates (ipropertymanagement.com)

[5] The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco | NBER

[6] What does economic evidence tell us about the effects of rent control? | Brookings

[7] Microsoft Word – Rent Control Literature Review Final 5 30 (nmhc.org); 2009-01-jenkins-reach_concl.pdf (econjwatch.org)

[8] Microsoft Word – Rent Control Literature Review Final 5 30 (nmhc.org)

[9] Where $5 Trillion in Pandemic Stimulus Money Went – The New York Times (nytimes.com);

[10] U.S. Inflation Rate by Year: 1929 to 2024 (investopedia.com)

[11] Apartment rent increase in the U.S. by state 2023 | Statista; State Inflation Tracker – United States Joint Economic Committee (senate.gov)

[12] Emergency Rental Assistance Program | U.S. Department of the Treasury; Federal Eviction Moratoriums in Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic (congress.gov); What Is the CARES Act? (investopedia.com)

[13] Average Rent by Year [1940-2024 ]: Historical Rental Rates (ipropertymanagement.com); State Population Totals: 2020-2023 (census.gov)

[14] National, State, and County Housing Unit Totals: 2020-2023 (census.gov); Apartment rent increase in the U.S. by state 2023 | Statista

[15] For journalists covering rent regulation, 4 studies to know (journalistsresource.org); Forty years of rent control: Reexamining New Jersey’s moderate local policies after the great recession – ScienceDirect

[16] Average Rent by Year [1940-2024 ]: Historical Rental Rates (ipropertymanagement.com)

[17] High Housing Costs Erode Confidence In U.S. Economy, Survey Finds (forbes.com)

[18] Cities With the Highest Rent in the U.S.: August 2022 | Rent. Research

[19] Average Rent by Year [1940-2024 ]: Historical Rental Rates (ipropertymanagement.com); Median Household Income in the United States (MEHOINUSA646N) | FRED | St. Louis Fed (stlouisfed.org)

[20] Average Rent by Year [1940-2024 ]: Historical Rental Rates (ipropertymanagement.com); March 2024 Rent Report – Rent. Research

[21] What Are the Long-run Trade-offs of Rent-Control Policies? (stlouisfed.org)

[22] What does economic evidence tell us about the effects of rent control? | Brookings

[23] The End of Rent Control in Cambridge | NBER

[24] An overview of rent stabilization from national housing experts | Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis (minneapolisfed.org)

[25] Rent Control 101 | Berkeley Rent Board (berkeleyca.gov)

[26] Rental Statistics | Rental Clock | Rental Protection Agency; The Biggest Landlords of Single-Family Rental Houses and Multifamily Apartments: Who Owns the US Housing Stock? | Wolf Street; Landlord Statistics by Category, Income, Unit, & More (doorloop.com)

[27] Microsoft Word – Rent Control Literature Review Final 5 30 (nmhc.org)