Research

August 31, 2016

Reformed Saudi Economy Could Be Good for Oil Markets

Summary

- In the past, oil price manipulation from foreign, government-run oil markets led to high prices, which correlated strongly with poor economic growth in the U.S.

- Increased oil production in the United States not only lowers prices and increases energy independence, but decreases the market share of price-manipulating oil cartels.

- Oil-reliant Saudi Arabia’s decision to privatize much of its economy (including a portion of the government-owned oil company) is good policy that could improve the freedom of international oil markets.

Introduction

For years the Saudi government has been bolstered by high oil profits that supported a bloated bureaucracy. A New York Times piece estimated that the government employs seventy percent of the workforce, and historically more than 80 percent of government revenues have been from oil. The steep drop in prices though has brought economic woes to Saudi Arabia, and now it is looking to privatization as an economic panacea.

Saudi economic reform could have implications for U.S. energy prices. Around 75 percent of global oil markets are controlled by governments, but Saudi Arabia’s reform combined with increasing U.S. oil production could help reduce this share and minimize government influence on oil markets.

Why We Care About Global Oil Markets

The U.S. is the world’s largest consumer of petroleum products at about a fifth of global consumption (around 19 million barrels every day). The U.S. consumes so much petroleum that it plays a major role in our economic vitality, especially since we must import so much of it (about a quarter of U.S. petroleum is imported). Essentially, the more Americans must spend on energy consumption, the less they are able to spend on increasing their quality of life. Cheap oil spurs economic growth, and expensive oil constrains it.

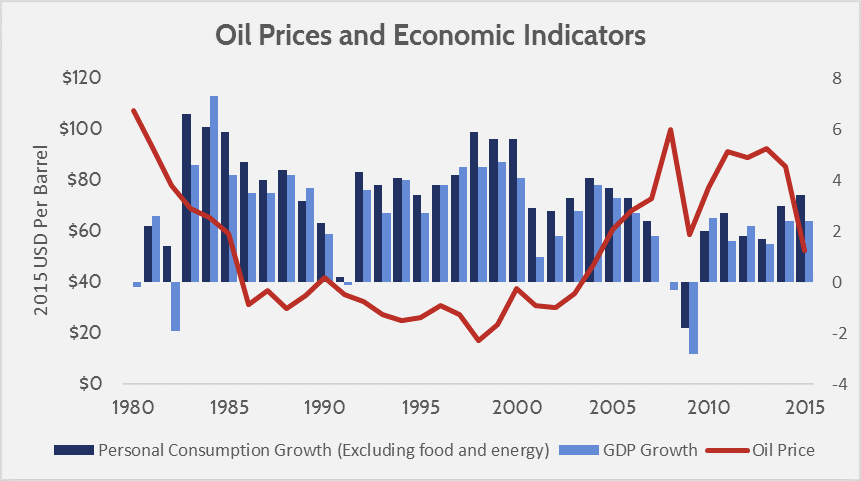

Source: EIA and Federal Reserve Economic Data.

Source: EIA and Federal Reserve Economic Data.

The graph above illustrates the relationship between oil prices and GDP growth. Consumption growth is also included, showing how it directly affects consumers. Oil is not the only factor in economic growth, but a reliance on expensive energy imports can make us more vulnerable to an economic downturn when prices rise.

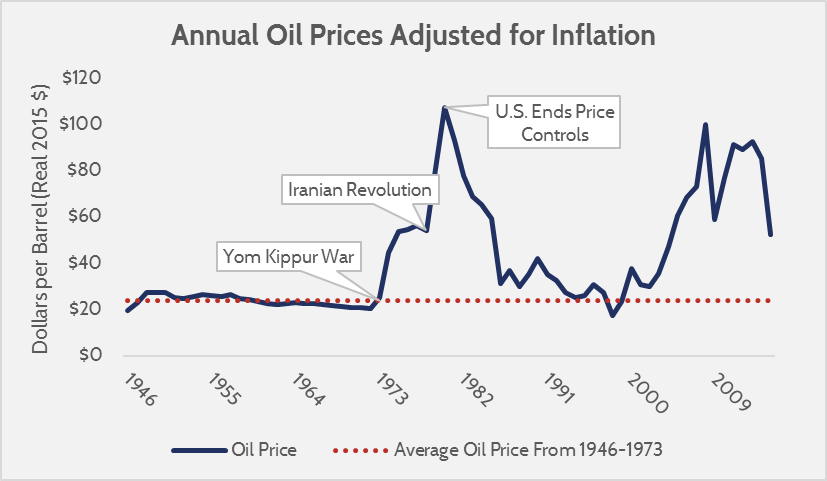

The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and the ‘Energy Battlefield’

In 1980, oil prices were $38/barrel ($107/b in today’s money), and President Carter declared the price manipulation of OPEC a “clear and present danger” to the United States, likening it to an “energy battlefield.” The U.S. was suffering from its second oil crisis in less than a decade, the first one being caused by an embargo against the U.S. over its support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War. High energy costs pushed the U.S. into a recession, and the U.S. adopted policies to reduce reliance on oil imports. The most successful of these was the ending of price controls in 1981, which allowed U.S. producers to profit from the high prices, incentivizing production.

Source: Inflation Data and EIA data.

Source: Inflation Data and EIA data.

One would think that a repeat of these oil crises is unthinkable now that U.S. oil production has effectively doubled. In a few years the U.S. has gone from importing 60 percent of its petroleum to 25 percent. During the oil crisis though, the U.S. only imported about 35 percent of its petroleum, yet was still vulnerable to price manipulation. How close the U.S. is to energy independence is not an adequate measure of energy security.

They’re not Shares of Free Markets; they’re Shares of Markets Made Free

The big difference between 1979 and 2016 is that OPEC controlled over half of global oil production back then, but only around 45 percent of oil production now. Increasing U.S. production is expected to cause OPEC’s market share to further reduce to around 40 percent by 2020, and continue decreasing for the foreseeable future. In lay terms, more oil producers will sell at the most competitive price, and less will collaborate to drive prices up.

The rest of OPEC is also struggling to maintain its market share. Governments propped up by oil revenue failed to privatize or properly reinvest in oil exploration and production. OPEC members everywhere except the Middle-East are expected to have declining production.

This is where Saudi Arabia’s move towards privatization will have an impact on future oil markets. Saudi Arabia plans to privatize part of ARAMCO (Saudi Arabia’s government owned oil company), and this will improve its efficiency and help to grow profits and production. Although the Saudi government will still regulate production levels as part of oil policy, adjusting production to manipulate prices could have consequences to the value of the privatized portion of ARAMCO, making it a costlier policy.

Increased Saudi production coupled with declining overall OPEC production also means that Saudi Arabia will have more influence over OPEC production and oil pricing. This is good news for the U.S., which has enjoyed a friendlier relationship with Saudi Arabia than other OPEC members, further reducing the likelihood of OPEC attempting to punish Americans over foreign policy positions.

Can Saudi Arabia Actually Achieve Economic Reform?

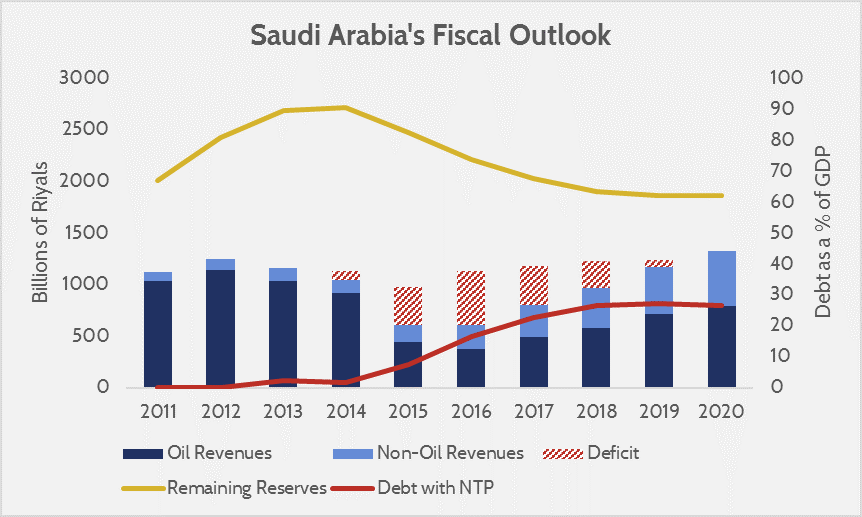

Saudi Arabia’s National Transformation Plan (NTP) will call for privatization, increased foreign investment, dramatically reduced subsidies, and massive job growth. Such policies sound great on paper, but can they actually pull it off? An IMF projection showed that Saudi Arabia could be “bankrupt” in five years, making it hard to imagine the Kingdom as being able to foot the bill for such a massive economic reform. However, a combination of debt and currency reserves can keep deficits manageable for a time.

Source: AAF Estimates, IMF Article IV Consultations, and Saudi Arabia Ministry of Finance

The IMF says Saudi Arabia’s NTP has the “right level of ambition,” and the data seems to agree with this. We applied the projections from the IMF’s annual report on Saudi Arabia to the EIA’s projected oil prices. Saudi Arabia can afford to pay now for an economic reform that could have big dividends later, bolstering what used to be virtually non-existent non-oil revenues. Fiscally, this is a move that makes sense for Saudi Arabia, and the timing is good, thanks to large foreign currency reserves.

The World Bank’s Chief Economist for the Middle-East notes that the low oil prices are perversely the best thing that could have happened to oil dependent regimes, finally forcing them to move away from draining subsidies and bad fiscal policy. However, Saudi Arabia is able to make the plunge into reform thanks to its massive safety net of currency reserves. Other oil producers desperately in need of reform but already drowning in debt, such as Venezuela, may have a harder transition to privatization if and when it comes.

Conclusion

Despite the “energy revolution,” the U.S. still is and will be a major importer of petroleum. U.S. energy security goes beyond energy independence, and will benefit greatly from an increasingly large share of oil production being privatized. The U.S. should encourage and support Saudi Arabia on its path to privatization, as it would have benefits for long term energy security, and potentially yield economic opportunities as well.