Research

October 24, 2017

Medicare Part D: Advancing Patient Health Through Private Sector Innovation

Introduction

The Medicare Part D program has achieved the rarest of distinctions among federal entitlement programs: it is both highly successful in its mission, and consistently comes in under budget. These accomplishments earn it high praise from policymakers on both sides of the aisle, as well as the beneficiaries it serves. The program’s success can be measured through multiple metrics. First, the program affords tens of millions of seniors more comprehensive health care by providing access to prescription drug coverage which most did not previously have. Second, Medicare Part D has cost both patients and taxpayers substantially less than originally projected. These factors lead beneficiaries to continuously report extremely high levels of satisfaction with the program.

Medicare Part D’s success is primarily a result of its structure—private health insurers compete against one another for seniors’ business. In fact, the program has been so successful that the number of options available to beneficiaries across the country not only necessitates competing insurers provide convenient access to a broad range of medicines at the best price, but also incentivizes them to provide additional services beyond the standard benefit. The success of the Part D program is a testament to the strength of the private sector’s ability to innovate and meet the demands of its customers. The tenets of the program that allow that success to occur should serve as a model for other government programs.

Success on Many Fronts

In 2018, beneficiaries in every state will have access to at least 19 stand-alone Medicare Part D plans, as well Part D plans offered in conjunction with Medicare Advantage plans (MA-PD).[1] The substantial number of options available provides for a robust marketplace throughout the country, improving outcomes for the program’s beneficiaries and for the taxpayers who finance more than three-quarters of the program’s basic benefits.

Previous research by the American Action Forum (AAF) found that as of 2012, total program expenditures were on track to be $500 billion less than expected – or only half of what was originally projected—over the initial 10-year period following implementation.[2] With a full ten years’ worth of data now available, AAF finds that outcome did indeed come true. In 2016, Part D expenditures were $100 billion, or less than half of the $205.5 billion cost projected by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in 2006.[3] In the first ten years of the Part D program, total expenditures were $555.8 billion less than originally projected.[4]

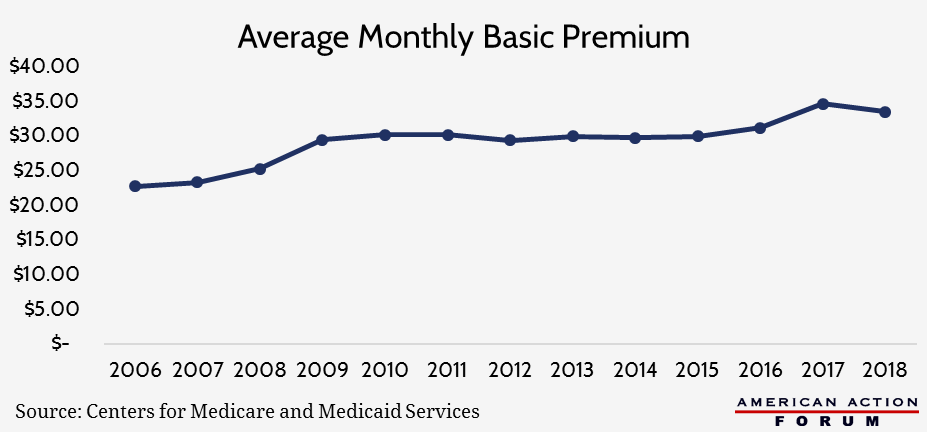

As shown above, the program continues to come in at lower-than-expected costs. Premiums have remained relatively flat since 2009[5] and will decline next year by 3.5 percent, despite increased use of expensive, new specialty drugs.[6]

The program’s relatively low costs have not, however, come at the expense of patient access to medicines or beneficiary satisfaction. When the program began in 2006, 20.4 million beneficiaries purchased a Part D plan, more than half of whom did not previously have prescription drug coverage.[7] Enrollment has grown every year, and now—just over a decade later—the program has more than doubled, serving approximately 43 million seniors.[8] Beneficiaries continuously report that the program is important, convenient, and provides a good value. For the seventh straight year, more than 85 percent of beneficiaries report overall satisfaction with the program.[9]

The creation of the program also contributed to expansion of the U.S. prescription drug industry. More companies entered the generic drug manufacturing space, which has helped reduce prescription drug costs by up to 85 percent.[10] Pharmaceutical companies invested more in research and development—particularly for diseases which disproportionately impact the elderly, and the number of drugs entering clinical trials increased between 37 and 52 percent immediately following passage of Part D.[11]

Factors Contributing to Success

The incentives in the Part D program—a function of a competitively bid process, along with the program’s patient protection requirements—have encouraged plan sponsors to be creative and innovate in order to attract enrollees.

The Part D program requires plan sponsors to engage in a bidding process, which puts downward pressure on costs. Simultaneously, Part D plans must provide a minimum level of actuarial value, coverage of drugs for each disease state, including at least two chemically distinct drugs in each class, and access to “all or substantially all” drugs in six specifically protected classes of medicines.[12]

Part D sponsors often alter the benefit design in numerous ways to provide beneficiaries with various options that offer differing levels of value for each patient, while still providing the required patient protections. For example, plans may offer various cost-sharing arrangements, alter their drug formularies, and establish preferred pharmacy networks that provide additional savings to beneficiaries. Plan sponsors have also developed various tools and methods to educate patients and improve their health. Finally, plan sponsors contract with Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) to provide additional services and savings to patients.

Consumer Engagement Tools

Before the start of each plan year, seniors can assess the range of plan options to determine which is best for them. Part D sponsors worked with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop a plan finder that allows beneficiaries to search the plans available to them and compare their expected out-of-pocket costs for each. Beneficiaries may enter information about the medicines they are currently using and evaluate the plans’ formularies and cost-sharing requirements before enrolling.

Other tools developed by plan sponsors help patients directly at the site of care. For example, UnitedHealthcare is making it easier for doctors to prescribe medications and for patients to know their exact cost before leaving the doctor’s office. Through United’s “PreCheck MyScript” online tool, doctors and patients can immediately see what a drug’s cost will be and use such information to make informed decisions, possibly prescribing a different medicine if the tool shows there is a cheaper one available.[13] The tool can also provide automated prior authorization, reducing the burden of making phone calls or sending faxes. CVS Health and Epic recently announced a partnership to provide similar capabilities to patients of CVS pharmacies and users of Epic’s electronic health record system.[14] These innovations save patients, as well as doctors and pharmacists, time and money; help ensure patients will adhere to their medication treatment plan; and allow for more integrated care, all of which improves patients’ wellbeing.

Price Negotiations

Part D sponsors and the PBMs they contract with save patients and taxpayers billions of dollars each year directly through price discounts and rebates negotiated on behalf of patients with manufacturers and other stakeholders throughout the supply chain.[15] A recent study found that PBMs saved patients and the Part D program $47 billion in 2014 through price negotiations.[16] Another study found that manufacturer discounts for drugs in 12 therapy classes widely used by Medicare patients reduced costs by more than a third , on average, relative to the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC).[17]

Utilization Management

Plan sponsors and PBMs implement a variety of utilization management tools to save money, primarily by encouraging greater use of less expensive drugs. This is typically achieved by setting more favorable patient cost-sharing rates for generic drugs, but may also result from requiring prior authorization or step therapy before approving more expensive medicines. These types of benefit design features ensure that patients first consider less expensive options, and the approaches are working. Nearly 80 percent of all drugs acquired through Part D are now generics[18], and in 2015, Medicare saved $67.6 billion—nearly $2,000 per beneficiary—due to the use of generic rather than brand-name drugs.[19]

Beneficiaries also benefit from methods used to assist them in sticking to their treatment plan. Poor medication adherence is responsible for unnecessary medical expenditures equal to up to an estimated 10 percent of annual U.S. health care costs.[20] Among older patients, an estimated 10 percent of hospitalizations are a result of nonadherence.[21] One medication therapy management program was found to reduce medication-related re-hospitalizations among older patients by an estimated 36 percent by connecting these high-risk patients with specially-trained community pharmacists after being discharged from the hospital and provided a return-on-investment of 2.6:1.[22] A demonstration in which dually-eligible patients with Hepatitis C received an in-house pharmacist consultation and frequent visits from a case manager saved $1.4 million by increasing medication adherence rates to 90 percent and successfully treating 90 percent of those patients.[23] Another method Part D sponsors use to increase medication adherence is to incentivize use of mail-order pharmacies, typically by reducing patients’ cost-share compared with using a brick-and-mortar pharmacy. OptumRx has succeeded in helping patients reach adherence rates of 80 percent by providing them with 90-day supplies of medications delivered right to their home.[24] The convenience of home delivery saves patients a trip to the pharmacy and helps ensure that patients receive their medication refill before they run out.

Improved Patient Experience

PBMs help coordinate increasingly fragmented care by keeping records of all of patients’ medicines and diagnoses, minimizing the risks posed by seeing multiple doctors and filling medicines at multiple pharmacies. With more than 81 percent of individuals age 65 and older having multiple chronic conditions, most of which are primarily treated with prescription medicines, this service is critically important.[25] BlueShield of California, for example, contracts directly with pharmacists to routinely review patients’ medication treatment plans (including use of over-the-counter medicines) and, when necessary, conduct clinical interventions on behalf of patients.[26]

Part D plan sponsors and PBMs employ nurses, nutritionists, patient educators, and specially trained pharmacists who are often on-call 24/7 to answer patients’ questions and educate them about how to get the most benefit out of their medications (i.e., when and how to take their medicines). Plan sponsors and PBMs often use specialty pharmacies to assist patients with complex medical needs to increase adherence to drug regimens and improve health outcomes. Some plan sponsors even have programs to ensure someone is proactively checking on patients and reminding them to take their medicines (particularly those with dementia or other diseases which might inhibit their ability or willingness to take their medicines according to the dosing schedule).

Value-Based Contracts

Most recently, drug makers and private insurers have begun entering into value-based contracts for prescription drugs in order to help ensure that patients truly are receiving the best value for their care. These contracts condition all or a portion of the reimbursement for a drug on some metric of the drug’s performance (or factor believed to be indicative of the drug’s performance) and/or the recipient’s health, typically after a pre-determined amount of time.

Lilly, for example, entered into a value-based contract with Harvard Pilgrim in 2016 for its diabetes drug, Trulicity; they signed a second such contract in 2017 for Forteo, an osteoporosis drug. Payment for Trulicity will be tied to performance of the drug relative to its competitors. Payment for Forteo will be partially dependent upon patients’ adherence rates since missed doses can dramatically reduce the drug’s effectiveness. In February 2016, Novartis entered into value-based agreements with Aetna and Cigna for its new drug to treat chronic heart failure, Entresto. Cigna’s payments will decrease dependent on the percentage of Entresto patients admitted to the hospital for heart failure; Aetna’s reimbursement is based on the drug’s ability to replicate the results from the clinical trials, and on the rate of heart failure-related deaths among patients taking Entresto.[27] Under both agreements, the drug will be on the preferred formulary, reducing patients’ out-of-pocket costs. CMS is now following the private sector’s lead and has entered into its first value-based contract for a prescription drug. While the details of the arrangement are still a little unclear, it seems CMS believes Part D sponsors are likely to achieve positive results with these types of value-based contracts.[28]

There are, however, several policies currently inhibiting drug makers and insurers from fully taking advantage of the potential benefits that these types of arrangements can provide. If efforts to try and resolve some of these policy conflicts are successful, it is likely that these types of contracts will become more common.

Conclusion

The Medicare Part D program proves that—with the right incentives coupled with appropriate consumer protections—a federal entitlement program can not only meet its mission, but do so under budget. The success of Part D can be largely attributed to its private-sector model which leverages competition and innovation to reduce beneficiaries’ drug costs and improve their overall health. The success of Part D should be applauded, and the factors that made it possible should be extended to other government programs.

[1] https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/the-medicare-prescription-drug-benefit-fact-sheet/

[2] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/109th-congress-2005-2006/reports/bartonltr2-16-05.pdf

[3] Congressional Budget Office, “Fact Sheet for CBO’s March 2006 Baseline: MEDICARE.” March 15, 2006.

[4] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/TrusteesReports.html

[5] https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicare-part-d-in-2016-and-trends-over-time-section-2-part-d-premiums/ , https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2017-Press-releases-items/2017-08-02-3.html

[6] https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Press-releases/2017-Press-releases-items/2017-08-02-3.html

[7] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2016.pdf (page 151),

Levy H, Weir DR. Take-Up of Medicare Part D: Results from the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2009;65B(4):492–501.

[8] https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2017.pdf (page 147)

[9] http://medicaretoday.org/resources/senior-satisfaction-survey/

[10] https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/resourcesforyou/consumers/buyingusingmedicinesafely/understandinggenericdrugs/ucm305908.pdf

[11] http://www.nber.org/papers/w13857.pdf

[12] https://www.kff.org/medicare/fact-sheet/the-medicare-prescription-drug-benefit-fact-sheet/

[13] http://www.drfirst.com/news/unitedhealthcare-simplifies-drug-prescribing-experience-care-providers-patients-precheck-myscript/

[14] https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cvs-health-and-epic-announce-initiative-to-help-lower-drug-costs-for-patients-by-providing-prescribers-with-expanded-visibility-to-lower-cost-alternatives-300536728.html

[15] http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/quintilesims-institute/reports/medicines-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2016-outlook-to-2021#key-findings-1

[16] http://www.affordableprescriptiondrugs.org/app/uploads/2017/06/ow-pbm-med-d-report-june-2017_final-1.pdf

[17] https://www.imshealth.com/files/web/IMSH%20Institute/Reports/IIHI_Estimate_of_Medicare_Part_D_Costs.pdf

[18] https://www.cms.gov/Newsroom/MediaReleaseDatabase/Fact-sheets/2015-Fact-sheets-items/2015-04-30.html

[19] http://www.gphaonline.org/media/generic-drug-savings-2016/index.html

[20] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3934668/

[21] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3934668/

[22] http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jgs.14518/full

[23] http://www.rsap.org/article/S1551-7411(17)30263-2/abstract

[24] https://www.optum.com/resources/library/new-adherence-study-90-day-home-delivery.html

[25] http://www.fightchronicdisease.org/sites/default/files/TL221_final.pdf

[26] https://www.blueshieldca.com/sites/medicare/plans-with-drug-coverage/prescription-drug-reference/medication-therapy-management.sp

[27] https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/xx/pdf/2016/10/value-based-pricing-in-pharmaceuticals.pdf

[28] http://www.raps.org/Regulatory-Focus/News/2017/09/14/28477/House-Reps-Seek-More-Transparency-on-Novartis-CMS-Pricing-Deal-for-Newly-Approved-CAR-T-Therapy/