Research

October 6, 2016

The Budgetary Costs of Donald Trump’s Child Care and Paid Maternity Leave Proposals

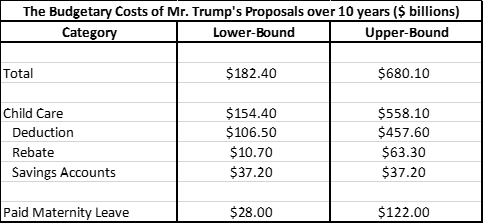

Recently, Donald Trump announced a series of proposals to reduce the out-of-pocket cost of child care spending and provide access to paid maternity leave. In this brief paper, we examine the budgetary implications of each of these proposals, as we previously did for Hillary Clinton’s child care and paid family leave proposals. The cost of Mr. Trump’s proposals will depend on how many households decide to start using child care because of the deduction and rebate, how many employers will opt for workers to use the government paid maternity leave program instead of their own paid leave benefit, and the size of the benefit that working women will receive while on maternity leave. Overall, we estimate that over ten years these proposals would cost the federal government anywhere between $182.4 billion and $680.1 billion.

Overview of Mr. Trump’s Child Care and Paid Leave Proposals

Mr. Trump plans to reduce household spending on child care and increase access to paid maternity leave with four proposals, three for child care and one for maternity leave. For child care, Mr. Trump would allow households to deduct child care expenses from their taxable income, provide a rebate for low-income households, and create a new tax-deferred Dependent Care Savings Account (DCSA). Mr. Trump would also guarantee six weeks of paid maternity leave by using the unemployment compensation system.

Child Care Cost Estimates

We estimate that all three child care proposals together would cost the federal government anywhere between $154.4 billion and $558.1 billion over the next ten years.

Deduction Proposal

Mr. Trump proposes to allow households to deduct child care expenses from their taxable income for up to four children. The deduction would be capped at the average cost of child care in the state of residence and only individuals with income under $250,000 ($500,000 if filing jointly) would be eligible. Stay at home parents would also be eligible to take the deduction.

To estimate the cost of this proposal we use 2014 annual household child care spending and income data from the March 2015 Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement. The budgetary cost of this proposal will depend primarily on how many households spend money on child care. For a lower-bound estimate, we assume that the percent of households that take the deduction will match the percent that paid for child care in 2014. We consider this a lower-bound estimate because it is likely that the deduction will lead to more households paying for child care. For an upper-bound estimate, we assume that every household with children under the age of 15 will start paying for child care. We do not expect the cost of the deduction to actually reach the upper-bound and simply consider it to be the total cost exposure of the program.[1]

While the CPS is useful for analyzing data on child care spending, it collects information on individuals, families, and households, but not tax units. Thus, we treated each household as a tax unit and assumed that married households filed jointly and unmarried ones filed individually. To account for the provision that the maximum size of the deduction for each child would be the average cost of child care in the state of residence, we used the average cost of infant care. The CPS, however, only indicates the total amount each household spends on child care and not the amount per child. Due to this limitation in the data, we estimated the cost of the plan if the deduction for total spending on child care for all children was limited to the per child average cost of infant care in the state of residence. In addition, Mr. Trump’s proposal has several other costly provisions that we are not able to take into account. These include stay at home parents being eligible for the deduction and households being able to take the deduction for elderly dependents. These factors make our estimates conservative in nature.

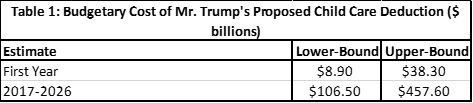

Table 1 contains our lower-bound and upper-bound cost estimates for Mr. Trump’s child care tax deduction.

On the lower end, if under Mr. Trump’s plan the number of households that take the deduction matches the number that paid for child care in 2014, the program would cost the federal government about $8.9 billion in its first year. Assuming the cost of program grows at the same rate as the projected nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the cost comes out to $106.5 billion over 10 years. On the upper end, if all households with children under 15 take the deduction, then the program will cost the federal government about $38.3 billion in its first year and $457.6 billion over 10 years.

Rebate Proposal

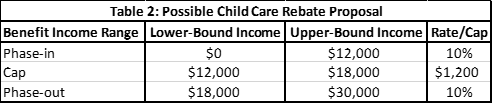

Mr. Trump proposes to use the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) as a vehicle to provide child care tax rebates to low-income households. The household rebate would be as large as $1,200 per year and the maximum income for households to be eligible would be $31,200. Although Mr. Trump’s proposal lacks a number of important specifics to fully analyze this exact program, the campaign provides enough details to analyze the cost of what would be a very similar program. We estimate the cost of a child care rebate that has a 10 percent phase-in and phase-out rate, a maximum benefit of $1,200, and a maximum household income eligibility threshold of $30,000. Table 2 contains the exact parameters of a child care rebate program that is likely similar to the one that Mr. Trump proposes.

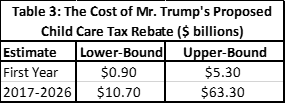

To estimate the cost of this child care tax rebate proposal we again utilize 2014 household child care spending and income data from the March 2015 CPS. As with the deduction, the cost of the rebate for low-income households will depend primarily on how many households pay for child care. Table 3 contains the lower- and upper-bound cost estimates for Mr. Trump’s child care tax rebate.

On the lower-end, if low-income households continue to pay for child care at the same rate that they currently pay for child care, the rebate will cost the federal government at least $900 million in the first year and $10.7 billion over ten years. On the upper-end, if all eligible households with children under 15 pay for child care, then the rebate will cost the government $5.3 billion in the first year and $63.3 billion over ten years.

Dependent Care Savings Account Proposal

Mr. Trump has proposed the creation of dependent care savings accounts, which would allow for annual tax-free contributions up to $2,000 for qualified child care expenses. Balances could carry-over and accumulate tax free. To encourage participation among lower income families, Mr. Trump proposes a 50-percent match of contributions up to $1,000, so the federal government would provide a maximum $500 grant in addition to the tax preference.

The proposal appears to closely resemble Dependent Care Flexible Spending Arrangements (DCFSA), which are offered as part of employer sponsored cafeteria plans. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, these plans are available to 40 percent of civilian workers, but only about 1.4 million Americans participate, with average contribution of $2,840. These plans provide an average tax benefit of $836, at an annual cost of $1.142 billion. Participation is skewed to higher income participants, with families making less than $50,000 comprising less than 5 percent of participants. While an imperfect analogue, DCFSA provides a useful proxy for estimating potential budgetary effects of Mr. Trump’s dependent care savings account proposal.

Assuming an expansion of the existing DCFSA participation to 100 percent of civilian workers and maintaining the current participation rate, the annual tax expenditures would increase to about $2.9 billion. Mr. Trump does not specify what the income limit would be for matching, but assuming the same share of the existing under $50,000 income cohort of DCFSA participants, and assuming the maximum $500 grant, the proposal would cost an additional $141 million. This estimate is highly uncertain, but is offered here for purposes of illustrating the potential magnitude of the cost to the taxpayer of about $3 billion annually, or a 10-year cost of $37.2 billion.

Paid Maternity Leave Cost Estimate

Mr. Trump would guarantee six weeks of paid maternity leave using the unemployment compensation system. The benefit would only be available to workers at businesses that do not offer their own paid maternity leave policy.

The budgetary cost of this program will depend primarily on how much of a worker’s wage will be replaced when on leave, a detail the campaign has yet to provide, and how many pregnant workers will already have access to paid maternity leave. According to Mr. Trump, the program will cost $2.5 billion annually if it were only available to workers who currently do not have paid maternity leave from their employer and the average weekly benefit were $300.

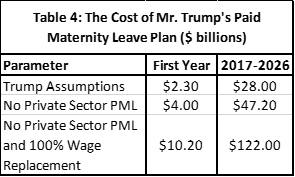

Table 4 contains a range of cost estimates for this program.

Using Census data on frequency of pregnancy among employed women and maternity leave benefits, we first test the campaign’s cost estimate. Assuming that recent rates of pregnancy and private paid maternity leave benefits do not change and the average benefit is $300 per week, we estimate the program would cost $2.3 billion annually or $28.0 billion over ten years, similar to the Trump campaign’s estimate.

There are a few issues, however, with this cost estimate. First, if policymakers were to implement this paid leave program, several employers already offering their workers paid maternity leave will likely opt to discontinue that benefit to take advantage of the one the government provides. This will be particularly true if many of the paid leave benefits offered by employers are less generous than the program Mr. Trump proposes. As a result, the portion of employers who offer paid maternity leave will likely fall substantially. Assuming that no employers provide paid maternity leave and an average weekly benefit of $300, Mr. Trump’s paid maternity leave program would cost the federal government about $4 billion in the first year and $47.2 billion over ten years.

Second, the Trump campaign’s assumption that the average weekly benefit would be $300 implies that the average wage replacement rate under this program would be 38.7 percent. That is, female workers on average would receive about 38.7 percent of their usual pay when on maternity leave. If Mr. Trump plans to make the wage replacement rate any higher, then the budgetary cost of this paid maternity leave proposal would increase substantially. In particular, if female workers would receive benefits equal to their regular compensation while on maternity leave, then the cost of Mr. Trump’s proposal grows substantially. In particular, assuming no employer provides workers paid maternity leave and a 100 percent wage replacement rate, the federal government would spend $10.2 billion in the first year and $122.0 billion over ten years to provide this benefit.

Conclusion: Total Cost of Mr. Trump’s Proposals

Combining the deduction, rebate, savings accounts, and paid leave program, Mr. Trump’s child care and maternity leave proposals would be quite expensive to implement. While more details are needed from the campaign to calculate a more precise estimate, these proposals together would cost anywhere between $182.4 billion and $680.1 billion over the next ten years.

[1] Note: In regard to the upper bound cost estimate of the deduction, it is impossible to determine how much all households with children under 15 would spend on child care. So to calculate this upper bound estimate we made a simplifying assumption that the distribution of taxable income before and after the child care deduction for these households match the distribution of taxable income before and after the deduction for households that are currently paying for child care. This may impact the upper bound estimate because incomes among households that pay for child care are on average higher than incomes among all households with children under 15.