Research

August 15, 2024

A Primer: The TCJA and S Corporations

Executive Summary

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) created a new deduction for pass-through business owners that allows S corporation shareholders to deduct up to 20 percent of their qualified business income from their federal income tax liability; this provision will expire in 2025 unless Congress acts to extend it.

- An S corporation is a business that elects to be treated as a pass-through business for federal income tax purposes, meaning its profits are “passed-through” to its owners (shareholders) and the owners record their allocated shares of the business’ profits as taxable income on their federal income tax returns.

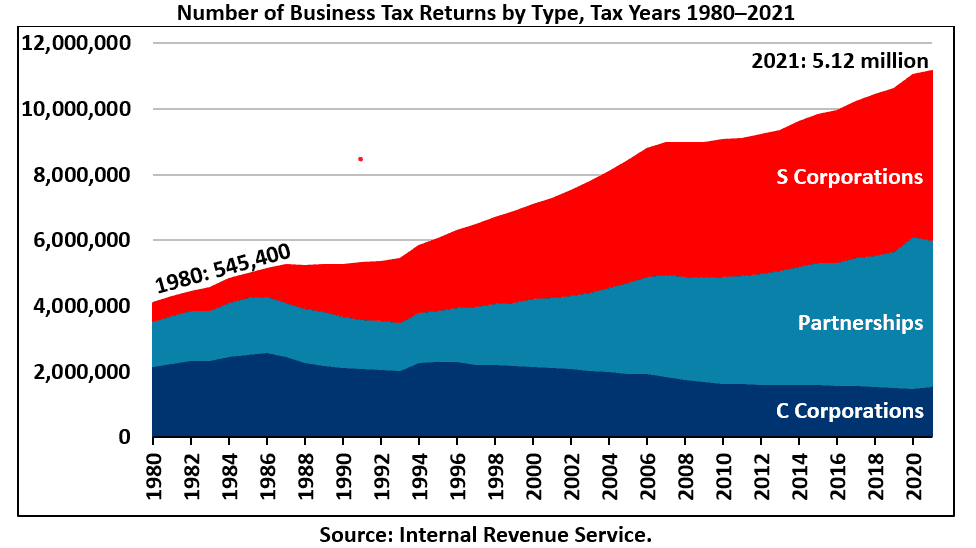

- The S corporation has become the dominant business structure in the United States; the number of businesses classified as an S corporation increased by 839 percent between 1980 and 2021, growing from about 545,400 to over 5.1 million.

- Because an S corporation passes its profits on to its shareholders, it is generally not subject to the 21-percent corporate income tax; its owners are instead liable for federal individual income and payroll taxes, as well as state and local income taxes.

Introduction

Before 1958, all U.S. businesses had two options when filing their federal income tax returns with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). They could elect to be treated as a C corporation and be subject to double taxation, in which they paid income taxes under Subchapter C of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), and the income they distributed to their owners (shareholders) as dividends was taxed again as personal income on their shareholders’ federal income tax returns. Or businesses could elect to be treated as a partnership or sole proprietorship and face a single layer of taxation, where their owners paid individual income taxes on their share of the businesses’ profits.

The burden of double taxation for C corporations made it difficult for small businesses to succeed in the U.S., while partnerships and sole proprietorships did not have liability protections, meaning their shareholders were personally responsible for the businesses’ debts and obligations. To address these issues, in 1958, as part of a broader tax bill known as the Technical Amendments Act of 1958, Congress added Subchapter S to the IRC, which created an additional federal tax filing status for U.S. businesses: the S corporation.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) reformed the federal taxation of S corporation shareholders by creating a new deduction for pass-through business owners that allows them to deduct up to 20 percent of their qualified business income (QBI) from their federal income tax liability. The TCJA’s reduced individual income tax rate structure and pass-through business provisions will expire on December 31, 2025, unless Congress acts to extend them. This deadline sets the stage for debate over the future of federal taxation of S corporations and other pass-through businesses in the U.S.

What is an S Corporation?

An S corporation is a business that elects to be treated as a pass-through business for federal income tax purposes. This means its profits are “passed-through” to its owners and the owners record their allocated shares of the business’s profits as taxable income on their federal individual income tax returns. As a result, a business that claims S corporation status is typically not subject to the 21 percent corporate income tax and its shareholders enjoy liability protections, in that they are not personally responsible for any of the business’s debts and liabilities. The business itself bears the burden.

The S corporation has become the dominant business structure in the United States, especially since enactment of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 and more recently since enactment of the TCJA, both of which lowered individual income tax rates and the latter of which provided additional tax relief for pass-through business owners. Between 1980 and 2021, the number of business tax returns filed with the IRS that claimed S corporation status increased by 839 percent, from about 545,400 to over 5.1 million. For comparison, over the same timeframe, the number of C corporations declined by 28 percent, from nearly 2.2 million to about 1.6 million. The number of partnerships increased by 224 percent, from nearly 1.4 million to about 4.5 million, but paled in comparison to the growth in businesses classified as S corporations.

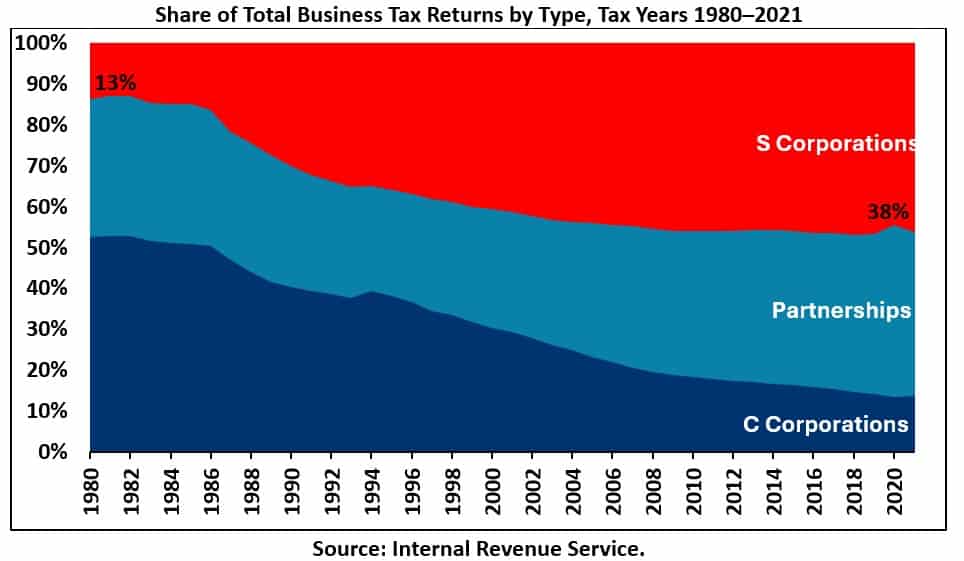

Put another way, while S corporations comprised just over 13 percent of all business tax returns filed with the IRS in 1980, they rose to 38 percent of all returns in 2021. By comparison, the share of total business tax returns filed by C corporations fell from nearly 53 percent in 1980 to about 35 percent in 2021, and the share of total returns filed by partnerships declined from 34 percent to 27 percent.

How Does a Business Become an S Corporation?

To qualify for S corporation status, a business must meet the following criteria: 1) it must be a domestic (U.S.) corporation; 2) it must have only allowable shareholders (this includes individuals who are U.S. citizens or residents, estates, certain trusts (grantor trusts, testamentary trusts, voting trusts, electing small business trusts, or qualified Subchapter S trusts)); 3) it must have 100 or fewer shareholders; 4) it must have only one class of stock; and 5) it must not be an ineligible corporation (certain financial institutions, insurance companies, and domestic international sales corporations are ineligible for S corporation status).

Any business that wishes to claim S corporation status is required to submit Form 2553: Election by a Small Business that is signed by all its shareholders to the IRS. The shareholders agree to report and pay taxes on their shares of the business’ income. A business’ S corporation status can be revoked with the consent of all shareholders that hold more than half of its outstanding shares of stock. If a business’ S corporation status is revoked, the business cannot elect S corporation status for five years without the consent of the IRS.

How Are S Corporations Taxed?

Since an S corporation passes its profits and losses directly on to its shareholders, it faces the same marginal tax rates as individuals and is generally not subject to any business taxation. This means its shareholders, not the business itself, pay federal income taxes and state and local income taxes.

While the business itself is generally not subject to taxation, it is still required to submit Form 1120-S to the IRS that reports its income, gains, losses, deductions, and credits to the agency for a given tax year. Form 1120-S is purely informational and helps the IRS know how much of the business’s profits or losses should be allocated to any shareholder for federal income tax purposes.

In tax year 2020, the last year for which comprehensive data from the IRS is available, 4.9 million Form 1120-S were filed with the IRS, showing a net income of $556 billion (total receipts minus total deductions) for U.S. businesses that claimed S corporation status. The data shows that 57 percent of S corporation receipts went toward the cost of goods sold (that is, the direct cost associated with making a product); about 17 percent went toward employee compensation (including salaries and wages, pension plans, and employee benefit programs); over 5 percent was spent on repairs, maintenance, rent, taxes, and licenses; 2 percent on depreciation; 0.8 percent each on bad debts and interest and advertising; 0.2 percent on amortization; and 10.7 percent on other miscellaneous deductions. The remaining 6.7 percent of receipts was recorded as net income. Other businesses spent similar percentages of their total receipts on the above categories.

Individual Income Taxes

For tax year 2024, the federal individual income tax rates start at 10 percent on the first $11,600 of taxable income ($23,200 for married filing jointly and $16,550 for heads of households) and rise to 37 percent on taxable income over $609,350 ($731,200 for married filing jointly and $609,350 for heads of households).

Tax Year 2024 Federal Income Tax Brackets and Rates, S Corporation Owners

| Rate |

Single Filers |

Married Filing Jointly | Heads of Households |

|

10% |

$0 to $11,600 | $0 to $23,200 |

$0 to $16,550 |

| 12% |

$11,601 to $47,150 |

$23,200 to $94,300 |

$16,550 to $63,100 |

| 22% |

$47,150 to $100,525 |

$94,300 to $201,050 |

$63,100 to $100,500 |

| 24% |

$100,525 to $191,950 |

$201,050 to $383,900 |

$100,500 to $191,950 |

| 32% |

$191,950 to $243,725 |

$383,900 to $487,450 |

$191,950 to $243,700 |

|

35% |

$243,725 to $609,350 |

$487,450 to $731,200 |

$243,700 to $609,350 |

|

37% |

$609,350 and over | $731,200 and over | $609,350 and over |

Source: Internal Revenue Service.

The income that shareholders receive from their S corporations may also be subject to the individual Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT). The AMT is a separate federal tax structure that requires some taxpayers to calculate their federal income tax liability twice – first under ordinary income tax rules and then under the AMT – and pay whichever amount is highest, thus increasing the effective tax rate paid by S corporation owners.

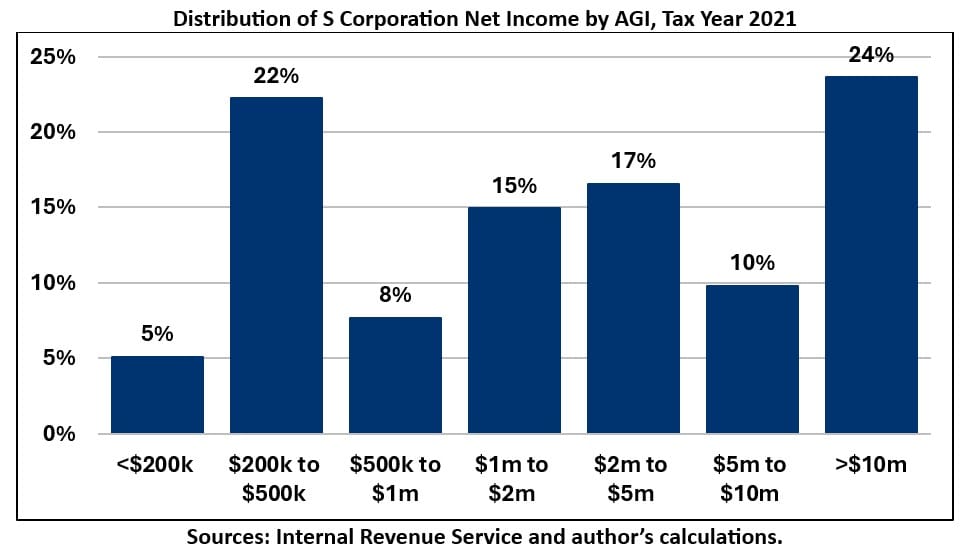

In tax year 2021, the last tax year for which comprehensive data from the IRS is available, 5.3 million federal individual income tax returns reported receiving nearly $674 billion of net income from S corporations. Taxpayers with an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $200,000 or greater earned just over 95 percent of S corporation income, while accounting for roughly 36 percent of returns reporting income from an S corporation. Conversely, taxpayers with an AGI of less than $200,000 earned about 5 percent of S corporation income but accounted for roughly 64 percent of returns reporting S corporation income.

A significant proportion of S corporation income is concentrated among high-income earners. In 2021, taxpayers with an AGI over $1 million, for example, received roughly 65 percent of all S corporation income, but comprised just over 6 percent of all returns reporting income from an S corporation. Taxpayers with an AGI over $10 million earned about 24 percent of all S corporation income but comprised less than 1 percent of all tax returns reporting S corporation income. On the flip side, net losses from S corporations were concentrated at the lower end of the income distribution. Taxpayers with an AGI of less than $20,000 received more than negative 4 percent of all S corporation income and comprised almost 9 percent of all returns. Since pass-through income and losses are one component of a taxpayer’s AGI, those that rely primarily on pass-through businesses for income will likely have a negative AGI if the business realizes losses. Losses could come from start-up businesses that are experiencing losses, failing businesses, or temporary business losses.

Distribution of S Corporation Shareholder Returns and Net Income by AGI, Tax Year 2021

| Adjusted Gross Income |

Returns Reporting Income from S Corporation |

% of Returns Reporting Income from S Corporation | Total S Corporation Income ($ billions) |

% of Total S Corporation Income |

|

Less than $10,000 |

320,835 | 6.02% | -$26.5 |

-3.9% |

|

$10,000 to $20,000 |

148,744 | 2.79% | -$1.0 |

-0.15% |

| $20,000 to $30,000 |

181,933 |

3.41% | $0.3 |

0.04% |

|

$30,000 to $40,000 |

213,495 | 4.00% | $1.0 |

0.14% |

|

$40,000 to $50,000 |

175,214 | 3.29% | $1.6 |

0.24% |

|

$50,000 to $75,000 |

511,677 | 9.59% | $5.6 |

0.83% |

|

$75,000 to $100,000 |

469,442 | 8.80% | $9.2 |

1.36% |

| $100,000 to $200,000 |

1,377,878 |

25.84% | $42.3 |

6.28% |

| $200,000 to $500,000 |

1,186,544 |

22.25% | $108.3 |

16.06% |

| $500,000 to $1,000,000 |

409,808 |

7.68% | $95.5 |

14.16% |

| $1,000,000 and over |

337,201 |

6.32% | $437.9 |

64.97% |

| Total |

5,332,789 |

100.00% | $674.0 |

100.00% |

| High Earners | ||||

| $1,000,000 to $2,000,000 |

189,234 |

2.43% | $100.7 |

14.94% |

| $2,000,000 to $5,000,000 |

96,764 |

1.11% | $111.7 |

16.58% |

| $5,000,000 to $10,000,000 |

28,892 |

1.81% | $66.1 |

9.81% |

|

$10,000,000 and over |

22,311 | 0.54% | $159.4 |

23.64% |

| Total |

337,201 |

6.32% | $437.9 |

64.97% |

Sources: Internal Revenue Service and author’s calculations. Figures may not sum due to rounding.

Payroll Taxes

The taxation of S corporation owners differs in how self-employment (SE) payroll taxes – which fund Social Security and Medicare – and the Affordable Care Act’s 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) apply to them. The owners of S corporations are classified as either active shareholders or passive shareholders. Active shareholders participate in the day-to-day activities of the business; therefore, they generally receive two types of income from their S corporation – wage income and profit distributions. The wage income of active shareholders is subject to SE payroll taxes, which are 15.3 percent (12.4 percent for Social Security and 2.9 percent for Medicare) on the first $168,600 of income and 2.9 percent on the next $31,400 of income, as well as the 3.8 percent NIIT on all investment income above $200,000. The profit distributions of active shareholders are not subject to payroll taxes.

Tax Year 2024 Payroll and Self-Employment Rates for a Single Filer

| Taxable Earnings |

Social Security |

Medicare |

Total |

| $0 to $168,600 |

12.4% |

2.9% |

15.3% |

| $168,600 to $200,000 |

0% |

2.9% |

2.9% |

| $200,000 and over |

0% |

3.8% |

3.8% |

Source: Social Security Administration.

As an example, if an active shareholder of an S corporation receives $300,000 from the business, $150,000 of which is wage income and $150,000 of which is a profit distribution, he or she would pay $22,950 in payroll taxes (15.3 percent of $150,000) and the rest would be exempt from the payroll tax.

In contrast, passive shareholders are not involved in the day-to-day operations of their respective S corporation and thus they only receive profit distributions from the business. The profit distributions are not subject to the payroll tax but are subject to the 3.8 percent NIIT, which is levied on investment income above $200,000 ($250,000 for married filing jointly and $200,000 for heads of households).

To illustrate, if a passive shareholder receives $300,000 in profit distributions from the business, he or she would pay $3,800 in an NIIT burden (3.8 percent of $100,000, since the first $200,000 of profit distributions would be exempt from the NIIT).

The difference in federal taxation of active and passive shareholders has been an area of contention between S corporations and the IRS. Since the wage income of active shareholders is subject to payroll taxes, S corporations have an incentive to pay their active shareholders in dividends instead of wage income to avoid payroll taxes. The IRS has sought to prevent this by reiterating that under the law, S corporations must pay reasonable compensation to shareholder employees in return for services before any dividends are distributed to them. Failure to comply could result in dividends being reclassified as wage income for federal income tax purposes.

State and Local Income Taxes

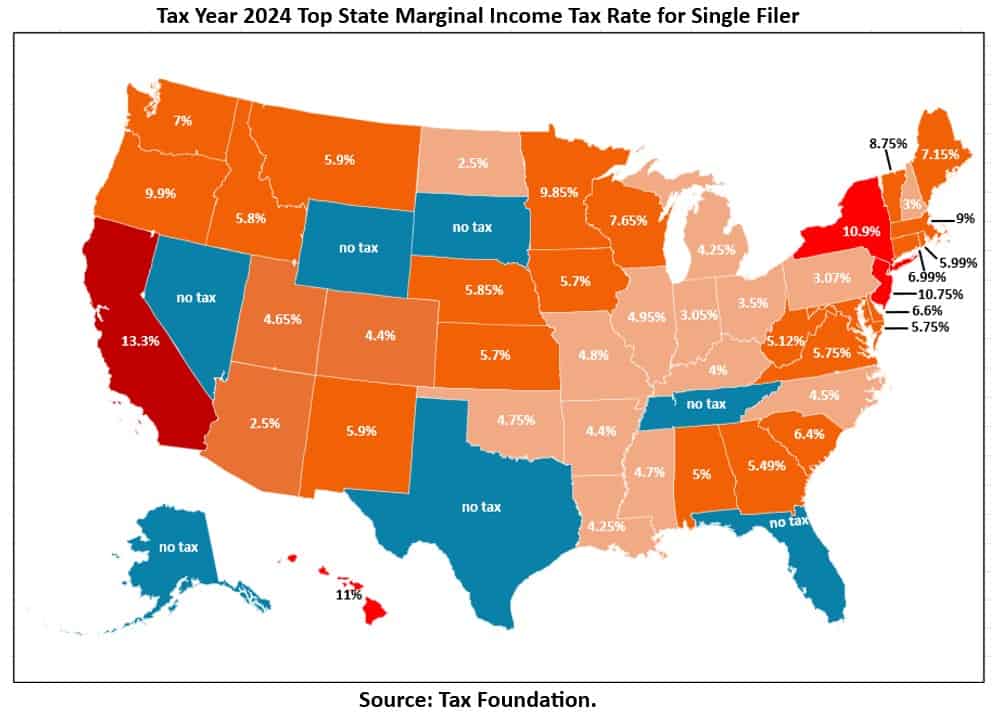

In addition to federal income and payroll taxes, S corporation owners pay state and local income taxes, which vary from zero percent in states without personal income taxes – Alaska, Florida, Nevada, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming – to 13.3 percent – the top marginal income tax rate in California. (For a full breakdown of 2024 state income tax rates and brackets, see Tax Foundation “State Individual Income Tax Rates and Brackets, 2024.”)

Corporate Income Taxes

An S corporation could be subject to the 21 percent corporate income tax under certain circumstances – one being the recognition of a built-in gain. A built-in gain occurs when a business disposes of an asset during its first decade of being classified as an S corporation that had appreciated in value when and if the business was previously classified as a C corporation. To the extent that the built-in gain exceeds the corporate income tax owed on it, the built-in gain passes through to shareholders who must report the gain as taxable income on their federal income tax returns. The corporate income tax could also be levied to recapture previous benefits from the use of investment credits or the last in, first out inventory method when and if the S corporation was previously classified as a C corporation. Or it could be imposed when more than one-quarter of a converted corporation’s gross receipts consists of passive income.

How Did the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Affect S Corporations?

The TCJA made significant changes to the federal tax treatment of individuals and corporations. A key provision in the legislation was the permanent reduction of the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent. During debate over the TCJA, pass-through business owners sought comparable tax relief to the corporate rate reduction, since their profits are passed through to their shareholders and are thus subject to individual income, not corporate, taxation. The result was lower federal individual income tax rates of 10, 12, 22, 24, 32, 35, and 37 percent and a new deduction for pass-through businesses under Internal Revenue Code Section 199A. The Section 199A deduction allows eligible individuals, trusts, and estates with pass-through business income to deduct up to 20 percent of their QBI[1] from their taxable ordinary income. The maximum deduction an S corporation owner can claim in a given tax year is the lower of 20 percent of their QBI or 20 percent of their taxable ordinary income (excluding capital gains). While most of the TCJA’s business tax changes are permanent, the law’s reduced individual income tax rate structure and pass-through business provisions expire on December 31, 2025.

The Section 199A deduction has two limitations that can lower a shareholder’s maximum deduction to less than 20 percent of their QBI. The first is a wage and qualified property (WQP) limitation that reduces a shareholder’s maximum deduction with a formula based on their share of the business’s W-2 wages and the original cost of its qualified assets. The second is a specified service trade or business (SSTB) limitation that reduces the maximum deduction if a shareholder has a stake in a business that’s involved in certain areas[2]. The WQP and SSTB limitations phase in at a lower taxable income threshold of $191,950 for single filers and $383,900 for couples in tax year 2024 and their full impact materializes when taxable income exceeds $241,950 for singles and $483,900 for couples.

The rules governing use of the Section 199A deduction allow for three basic outcomes for S corporation owners, which are illustrated below.

- Outcome 1: S corporation shareholders with taxable income at or below the lower income threshold for a given tax year (currently $191,950 for singles and $383,900 for couples) may take the full 20 percent Section 199A deduction. To illustrate, suppose I am a shareholder that is a single filer with taxable income of $190,000, no capital gains, and my QBI is $150,000. Under this scenario, my taxable income of $190,000 is below the lower income threshold of $191,950 for 2024, so I can claim the maximum Section 199A deduction equal to the lesser of 20 percent of my QBI or 20 percent of my ordinary income. Under this scenario, my deduction would total $30,000 ($150,000 QBI multiplied by 20 percent).

- Outcome 2: S corporation owners with taxable income between the lower- and upper-income thresholds ($191,950 to $241,950 for singles and $383,900 to $483,900 for married filing jointly) can take a reduced deduction because they are subject to SSTB and WQP limitations. For S corporation owners with SSTB or non-SSTB income, their allowable deduction is contingent on their applicable percentage[3], which is used to calculate a reduction amount that’s subtracted from their deduction to determine the ultimate Section 199A deduction they can claim. To illustrate, suppose I am a shareholder that is a single filer with taxable income of $220,000, no capital gains, and my QBI is $200,000. In addition, my share of the business’s W-2 wages is $70,000 and my share of its unadjusted of qualified property is $100,000. Under such a scenario, my QBI comes from a non-SSTB and my taxable income is within the range for the WQP limit. Thus, the deduction I can claim is equal to my maximum Section 199A deduction, minus my deduction under the full WQP limit, multiplied by my applicable percentage. My applicable percentage would be 56 percent, my deduction with no WQP limit would total $40,000, and my deduction with the full WQP limit would be $35,000. As a result, my reduction amount is $2,800, and thus my deduction would total $37,200.

- Outcome 3: S corporation owners with taxable income above the 2024 upper income threshold ($241,950 for singles and $483,900 for couples) can claim a deduction for non-SSTB income that does not exceed the larger of 50 percent of a shareholder’s portion of the business’s W-2 wage base or 25 percent of those wages plus 2.5 percent of a shareholder’s portion of the business’s unadjusted basis (that is, original cost) of qualified property placed in service within the past decade. To illustrate, suppose I am a shareholder that is a single filer with taxable income of $250,000, no capital gains, and my QBI is $150,000. In addition, my share of the business’s W-2 wages is $70,000 and my share of its unadjusted basis of qualified property is $100,000. Under such a scenario, my QBI comes entirely from a non-SSTB and my taxable income is above the upper income threshold for a single filer in 2024. As a result, the deduction I can claim is subject to the WQP limit, meaning it cannot exceed the larger of 50 percent of my share of the business’s W-2 wages or 25 percent of W-2 wages plus 2.5 percent of my share of the business’s unadjusted basis of qualified property – $35,000 or $20,000. Under this scenario, my deduction would total $35,000.

Summary of Outcomes for Section 199A Deduction for Illustrative S Corporation Shareholders

| Outcome |

SSTB Limit? |

WQP Limit? |

Deduction |

Deduction Amount |

|

Outcome 1: S corporation shareholder is a single filer with taxable income below the lower income threshold of $191,950 |

No |

No |

Full Section 199A deduction equal to the lesser of 20% of QBI or 20% of taxable income minus capital gains |

$30,000 |

| Outcome 2: S corporation shareholder is a single filer with taxable income between the lower- and upper-income thresholds of $191,950 to $241,950 |

No |

Yes |

Maximum Section 199A deduction is reduced by an amount equal to the shareholder’s applicable percentage multiplied by the difference between the Section 199A deduction with and without the WQP limit |

$37,200 |

| Outcome 3: S corporation shareholder is a single filer with taxable income above the upper income threshold of $241,950 |

No |

Yes |

Section 199A deduction is the lowest of 20% of QBI, 20% of taxable income minus capital gains, or Section 199A deduction with full WQP limit |

$35,000 |

Sources: Congressional Research Service and author’s calculations.

Whether to extend, modify, or let the Section 199A deduction sunset is something Congress will have to consider at the end of next year, in tandem with the expiration of a majority of the TCJA’s provisions.

Conclusion

Over the past several decades, the S corporation has become the dominant business structure in the United States, eclipsing the number of domestic corporations that elect to be treated as a C corporation or partnership or sole proprietorship for federal income tax purposes. The number of S corporations increased by 839 percent between 1980 and 2021, growing from 545,400 to over 5.1 million. They are treated as a pass-through entity for federal income tax purposes; they avoid the 21 percent corporate income tax, and their owners are instead liable for federal income taxes on the profits they earn from the business. The TCJA provided additional tax relief to S corporation owners by allowing them to deduct up to 20 percent of their business income federal income tax liability, but this policy expires at the end of next year, thus setting the stage for debate over the future of taxation for S corporations and other pass-through businesses.

[1] QBI is the net amount of income, deductions, losses, and gains for a pass-through business.

[2] These areas include accounting, actuarial science, athletics, brokerage services, consulting, financial services, health care, investing and investment management, law, performing arts, as well as dealings in securities, partnership interests, and/or commodities.

[3] Applicable percentage refers to the ratio of a shareholder’s taxable income minus the applicable lower income threshold of $50,000 for singles and $100,000 for couples.