Insight

November 13, 2019

What Should Budget Process Reform Look Like? Reviewing the Bipartisan Congressional Budget Reform Act

Executive Summary

- The Bipartisan Congressional Budget Reform Act substantially reforms the federal budget cycle – including by formalizing biennial budgeting.

- It creates a new fast-track mechanism for reducing deficits.

- It establishes new procedures, reporting requirements, and institutional modifications to enhance the federal budget process.

Introduction

Occasional reminders of the nation’s growing debt and periodic federal government shutdowns are likely the extent of most Americans’ familiarity with federal budget practice. Indeed, it is surely to their credit that Americans have other things to occupy their days other than the labyrinthine process by which federal policymakers apportion taxpayer funds. Among a broad swath of observers and practitioners, however, there is broad agreement that the congressional budget process has room for improvement. This past Wednesday, a bipartisan group of 15 members of the Senate Budget Committee agreed and advanced The Bipartisan Congressional Budget Reform Act out of the committee.

The Act is the first major process reform reported out of the committee since 1990 and offers a meaningful improvement in how Congress goes about its budgeting business. Broadly, the Act improves the budget calendar, formally institutionalizing the recent practice of two-year budgeting while creating new mechanisms that could, should Congress so choose, reduce some of the risk of budget-driven crises such as shutdowns and defaults on the debt limit. The Act did not settle long-running disagreements about the size of government, the right level of taxation, or what the nation’s spending priorities should be. Instead, the Act should make the job of grappling with those issues more productive – and help keep the trains running along the way.

The Budget Calendar

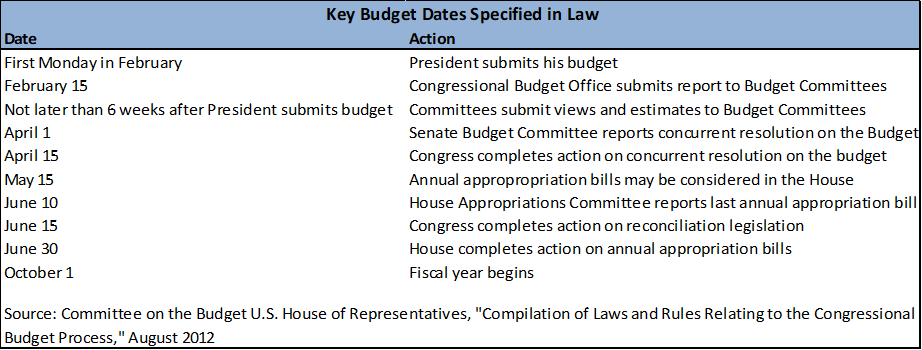

Section 300 of the Congressional Budget Act provides an orderly schedule for timing and sequence of major elements of the budget process such as the date for the submission of the president’s budget, the date by which Congress must complete a budget, and a number of other key budget events.

It is unclear if Congress and the president have ever fully adhered to this schedule since its inception in 1974. Deadlines are regularly missed, and Congress routinely short circuits the process by other means. Instead of following this process, in recent years the budget process has been characterized by the submission of the president’s budget, which is increasingly a messaging document, at a time of the president’s choosing followed by congressional careening until the enactment of a two-year budget deal.

The Act would shift congressional budgeting to a biennial process – though it would retain annual appropriations. This change is less consequential than it appears; Congress has essentially been operating on two-year budgets since the end of 2013. Formalizing this process would introduce some needed order to the current broken system. The president’s budget would also be submitted earlier, allowing the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) to consolidate several winter budget reports into a single annual scoring baseline – a useful change.

New Mechanisms

While the change in the budget calendar may be the most visible process reform by the Act, its more substantial reforms likely are the introduction of three new processes. The first is a new reconciliation procedure to reduce deficits. The Act requires that congressional budget resolutions incorporate debt-to-GDP ratios for each fiscal year covered by the resolution. It further requires that the CBO submit a report every two years evaluating whether the debt target for the last year of the most recently enacted budget resolution will be met. If not, the report must estimate what deficit reduction would be necessary to achieve the target. The Senate Budget Committee would be required to report a resolution of the amount of deficit reduction needed to meet the target along with instructions to committees, much like a normal reconciliation instruction, to report legislation reducing the deficit by specified amounts.

The Act would also introduce a new, bipartisan budget process. Recognizing that the congressional budget process is increasingly a partisan exercise, reflected in budget resolutions that are often messaging documents that only have the support of the majority, the Act provides for special consideration of a budget resolution with bipartisan support. If a budget resolution has the support of at least half of each of the majority and minority members of the committee and passes the Senate by at least 60 votes with the support of at least 15 members of the minority, it allows for expedited consideration of appropriations bills and would generate legislation setting forth both statutory spending levels and a new debt limit, consistent with the resolution.

Last, the Act includes a useful mechanism for adjusting the debt limit to conform to the debt levels set forth in the budget resolutions. Similar to past practice in the House of Representatives (the so-called “Gephardt Rule”), the Act includes a provision that would generate legislation adjusting the debt limit to that projected in the budget resolution.

Institutional Reforms

The Bipartisan Congressional Budget Reform Act includes a number of institutional reforms designed to address clear deficiencies in the budget process and improve budgetary information provided to lawmakers. Perhaps most conspicuously, the Act would rename the Senate Budget Committee, which would become the Committee on Fiscal Control and the Budget and would include as ex officio the chairs and ranking members of the Appropriations and Finance Committees.

Within the Senate, the Act would reform the practice of vote-a-rama, which forces votes on numerous amendments, typically of a partisan messaging nature, and likely suppresses lawmakers’ appetite for even considering a budget resolution. The Act further improves the system of points of order (how Senators formally protest budget violations in legislation) in the Senate, with a mind to improving the utility and durability of the system.

The Act makes several other changes to congressional budgeting practices, including a needed reform to the baseline that strips out anomalous funding such as for wars and other emergencies from future baselines, as well as new reporting requirements for CBO. The upshot is that lawmakers and observers will be better informed as to the scope, scale, and disposition of taxpayer dollars.

Conclusion

No process reform will substitute for regular and robust public policy debate about the proper size of the federal government. That debate is rightly the realm of elections and policy changes wrought through democratic institutions. Budget process reform should not seek to stack the deck in favor of one outcome of the debate over another. Rather, process reform should rely on experience and best practices to facilitate an informed and orderly system for channeling that debate into budgetary outcomes. The Bipartisan Congressional Budget Reform Act is a reform in that spirit, offering a modest but important improvement over the current budget process.