Insight

August 28, 2018

We Have Not Yet Begun to Fight

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), over the next decade federal debt held by the public will surpass 96 percent of the U.S. economy, and by 2048 the debt will be 152 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). The last time the debt approached these levels was during and immediately after World War II – in 1946 the federal debt was the highest it’s ever been on record, at 106 percent of GDP. By contrast, CBO does not assume a third global war in its future budget projections. Rather, CBO simply analyzed the budgetary trajectory of current U.S. laws, which will result in average deficits over the next decade of about $1.2 trillion.

Many observers are aware of the large and growing U.S. debt load and the fact that at some point policymakers will need to reverse this trend. What many don’t appreciate is that this effort will require an unprecedented fiscal consolidation to avoid a fiscal crisis.

Unlike after the second World War, our deficits cannot be erased by the transition from a war-footing to a peacetime economy. Rather, the United States will need to make fundamental changes to major health, retirement, and other spending programs as well as the tax code. To reduce the debt by 2048 to its 50-year historical average of 41 percent of GDP, the CBO recently calculated, policymakers would need to enact a fiscal consolidation of 3 percent of GDP each and every year compared to current budget projections. And this consolidation is only the primary deficit reduction required to achieve the debt target. CBO assumes, and its calculation relies upon, additional debt reduction from reduced interest costs and stronger economic growth.

A somewhat less ambitious debt target of 78 percent of GDP (the current level) in 2048 would require sustained, primary deficit reduction of 1.9 percent of GDP every year. Either approach would be unprecedented.

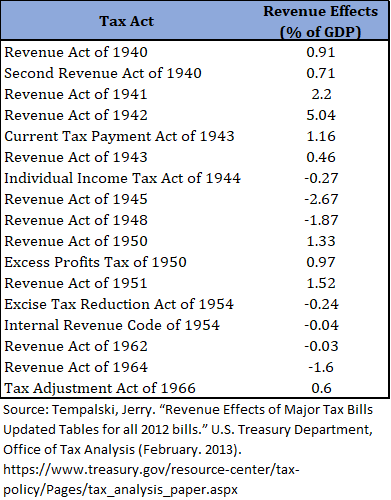

For perspective, consider the revenue effects of the major tax bills passed since 1940. Not a single tax bill since then ever put in place, on a sustained basis, the sort of deficit reduction required to reduce or stabilize the current U.S. debt going forward.

Table 1: Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills (1940-1966)

Table 2: Revenue Effects of Major Tax Bills (1967-2013)

Only one tax bill, the Revenue Act of 1942, had a deficit effect in a single year that met or exceeded what was needed to meet the 41 percent debt target. It was a temporary measure that the post-World War II tax cuts effectively undid.

For all the gnashing of teeth and rending of garments, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) will reduce revenues by an average of 1.1 percent of GDP over the next four years. Multiply the political rancor over that bill by 3 and assume it applies to Medicare and Social Security, too – that’s the magnitude of the federal debt challenge. Far worse, however, would be to continue on the present course, where policymakers either ignore or continue to add to the problem, forestalling an inevitable but far more difficult policy course.