Insight

April 10, 2017

The Trade Deficit is Not Hurting the Economy

Executive Summary

- President Trump’s primary goal in trade policy has been to reduce or eliminate the trade deficit

- However, the trade deficit is mainly driven by macroeconomic factors such as national saving and foreign investment in the United States – not trade policy

- International trade generates valuable productivity gains, gains for consumers, and economic growth. It should not be restricted to improve the trade balance

Since the start of his campaign, President Trump has vilified the U.S. trade deficit. He targeted China, Japan, Mexico, and most recently Germany by claiming that existing trade agreements are rigged in those countries’ favor. A little over a week ago, he signed an executive order directing the Secretary of Commerce and the U.S. Trade Representative to review our current trade relationships and determine the causes of bilateral trade deficits. He further called for a report within 90 days which will aid the administration in reducing our trade deficits.

This executive order should come as no surprise. However, the president’s actions may be straining U.S. relationships with our trade partners. Instead of continuing to use harsh rhetoric against our allies, the president should reconsider what the trade deficit is, why it occurs, and its true economic effects.

The Trade Deficit, Explained

Since 1976, The United States has run a trade deficit. This means that we buy more from the world than we sell. Trade mercantilists tend to view this as a negative; they believe that a trade deficit indicates a failure of trade policy. They reason that imports should be minimized to shield domestic industry from foreign competition, and that exports should be maximized to create a thriving economy.

Another school of thought contends that trade barriers are harmful to economic growth. It recognizes the value of both imports and exports as well as the economic progress brought about by international trade. This includes specialization, gains in efficiency, improvements in the quality of consumer goods, decreases in consumer prices, and increased productivity.

Regardless of which camp you are in, it is important to recognize that the trade deficit is influenced by much more than just trade policy. It is primarily responsive to macroeconomic forces such as net investment and saving in the United States. The fact that the United States is a net borrower, and that foreign investment in the United States exceeds U.S. investment abroad, are the true drivers of our trade deficit. Let me explain.

The U.S. balance of payments is comprised of the current account, financial account, and capital account. The current account includes the international trade of goods and services as well as unilateral transfers between nations (foreign aid, money sent from immigrants to their families back home, etc.). Both the capital and financial accounts measure different types of investments made either in or by the United States. This could be investment in factories, the purchase of stocks and bonds, or loans to governments, and is essentially a transfer of ownership.

Like the name suggests, the balance of payments must balance. A country with a current account surplus must have a capital and financial account deficit, and vice versa. This is the flip side of the trade deficit which is often forgotten. As long as investment into the United States continues to exceed national saving, we will have a trade deficit. The only way to reverse this would be to reverse the current relationship between saving and investment, either by discouraging domestic investment, implementing policies which encourage private saving, or reducing our budget deficit to increase public saving.

The following chart affirms this fact. By comparing import levels over the past 20 years with foreign direct investment (FDI) into the United States, it shows that growth in inward FDI closely mirrors growth in U.S. imports. This should make sense: after a foreign entity obtains U.S. dollars through international trade, those dollars are often invested back into U.S. assets such as treasury bonds or manufacturing facilities to make a profit.

One of the president’s top trade advisors recently warned against trade deficits and the corresponding investment they bring into the United States. Peter Navarro, Director of the new White House National Trade Council, contended that the trade deficit will ultimately lead to “conquest by purchase.” “In the long run,” he suggested, “we are all likely to be owned by foreigners.”

Navarro’s argument assumes that there is a fixed amount of assets in the United States, and that those assets will all eventually be foreign-owned. This is not the case. Americans will never stop creating businesses, building factories, or creating new wealth. For instance, total wealth in the United States more than doubled from $44 trillion in 2000 to over $90 trillion in 2015.

Foreign investment adds value by creating jobs for American workers. In 2014, majority foreign owned businesses employed 6.4 million Americans. The president is no stranger to these benefits: since taking office, he has met with several foreign companies in an effort to bring jobs to the United States.

The Trade Deficit’s Relationship to Economic Growth

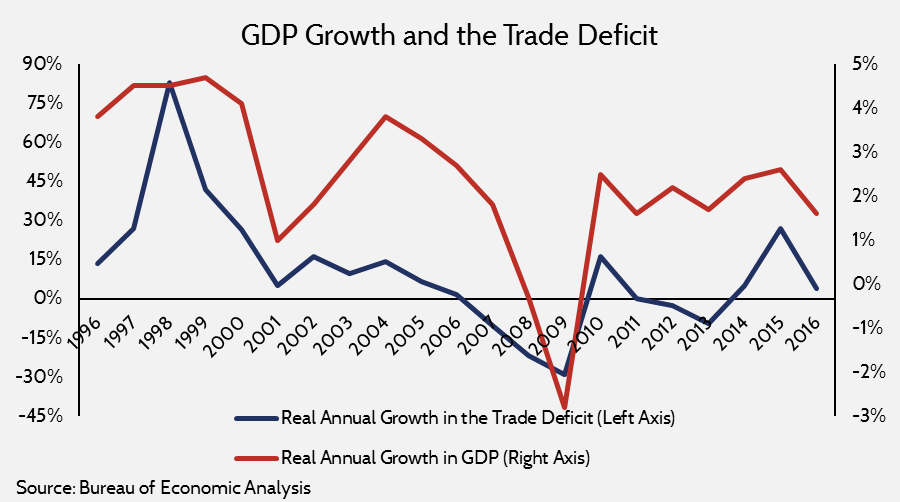

Advocates for reducing the trade deficit argue that it inhibits economic growth. Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross, when asked why trade deficits have occurred during periods of strong economic growth, claimed that there is no causal relationship between the two. In fact, he argued that “we’ll never know how much more growth there would have been without the trade deficit.” The problem with this is that the link between the trade deficit and economic growth is the rule, not the exception.

The above chart compares real annual growth of the U.S. trade deficit to real GDP growth over the past 20 years. The two are parallel: the trade deficit grows rapidly during periods of economic growth. Likewise, it declines during economic contraction. This is because consumer demand falls, inward FDI shrinks, and U.S. borrowing increases.

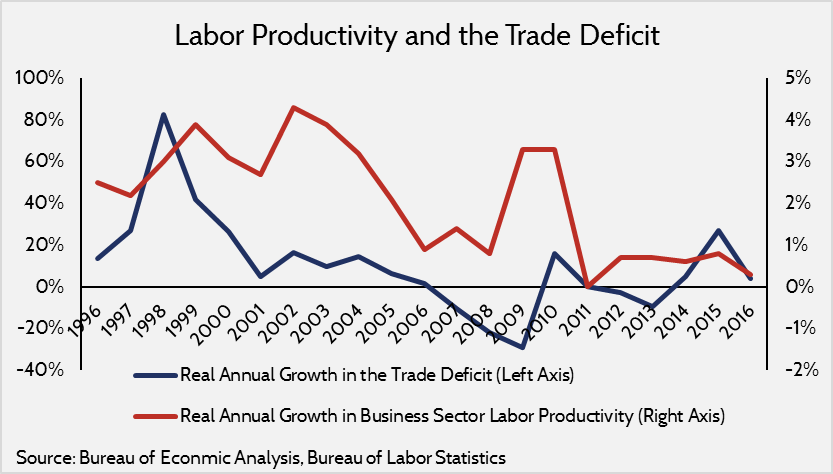

A similar link exists between U.S. productivity and the trade deficit (below). Productivity, measured here by output per hour of the nonfarm business sector, is another indicator of overall economic health. Therefore, it is not surprising that growth in labor productivity also mimics growth in the trade deficit. Trade introduces international competition and encourages specialization; this improves the productivity of labor.

The Trump Administration is expected to reopen negotiations of the North American Free Trade Agreement as early as this June. The president’s desire to eliminate the trade deficit will undoubtedly play a role. However, taking actions to reduce our trade deficits may harm our relationships with Canada and Mexico. Import restrictions are often met with retaliatory measures: after the United States halted a program which allowed long-haul trucking from Mexico into the United States, Mexico levied damaging tariffs on $2 billion worth of U.S. products. Similar retaliation should be expected today.

The trade deficit is not a result of trade policy, nor is it an indicator of poor trade agreements. It reflects the vibrancy of the U.S. economy and the fact that the United States is an attractive place to invest. This investment generates jobs, increases productivity, and contributes to economic growth. The primary goal of trade policy should be to reduce trade barriers both at home and abroad, not to reduce the trade deficit.