Insight

October 12, 2016

How TPP Would Help Small Business

Summary

- The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is the first trade agreement to include a specific chapter dedicated to facilitating trade for small and medium-sized businesses

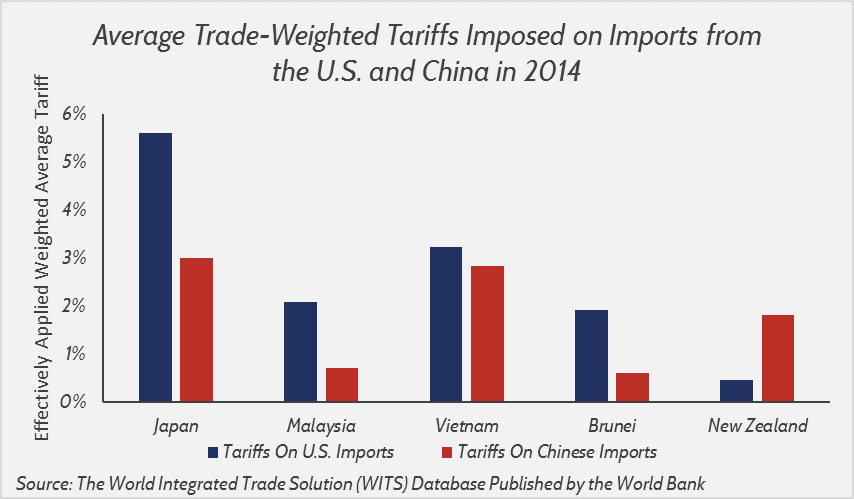

- Currently, TPP partners place higher tariffs on U.S. exports than Chinese exports

- TPP would level the playing field by eliminating 99 percent of all goods tariffs between the U.S. and TPP partners

The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) is a trade agreement that would link the U.S. to 11 other countries along the Pacific Rim. By reducing trade barriers between the U.S. and the Asia Pacific, TPP would increase our volume of trade and spur economic growth. It would also strengthen U.S. relationships with nations like Japan and Vietnam. Despite these potential benefits, both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are opposed to the agreement.

Critics allege that TPP was created by large corporations for large corporate interests. However, a significant portion of TPP was designed specifically to benefit small business. It is the first trade agreement in U.S. history to include an entire chapter dedicated to small and medium-sized businesses, which outlines several provisions that reduce small business-specific trade barriers. It also establishes a permanent new committee dedicated to advancing the interests of smaller businesses. The committee would educate small businesses about trade, ensure that small businesses are aware of all of the advantages available to them under TPP, and periodically meet to review how small businesses are utilizing the agreement and make reforms if necessary.

Approximately 98 percent of U.S. exporters are small and medium-sized enterprises (businesses with less than 500 employees). This means that TPP would disproportionally benefit smaller companies by eliminating thousands of foreign taxes on U.S. exports. It would also empower even more U.S. businesses to begin selling their products overseas. Currently, 49 percent of non-exporting small businesses are interested in exporting, but cite regulatory complexity and a lack of available information as barriers. TPP would establish new online resources with information on exporting, country-specific rules and guidelines, and relevant TPP provisions that make it easier for small businesses to export.

While the U.S. is an open market (the average U.S. tariff on imports is only 1.3 percent), many Asia Pacific nations have protectionist policies that restrict imports. These policies hurt almost 300,000 exporting small and medium-sizes businesses in the U.S. And taxes on U.S. products can be substantial: U.S. manufacturers face tariffs up to 100 percent in TPP markets while some agricultural exports are taxed over 700 percent.

The above chart compares average trade-weighted tariffs on goods from the U.S. and China. While none of the TPP partners listed above currently have trade agreements with the U.S., all except Japan have trade deals with China. Therefore, it should not be surprising that four of the five nations above tax U.S. imports more than Chinese imports. This means that U.S. goods are more expensive to TPP consumers than Chinese goods, and that Chinese exporters have a competitive advantage in these markets. TPP, however, would level the playing field: it would eliminate nearly 75 percent of goods tariffs between TPP partners immediately after going into effect, with 99 percent eliminated over 30 years.

The Asia Pacific is the fastest growing region in the world. By 2030, Asia will be home to 64 percent of the global middle class and account for over 40 percent of global middle class consumption. TPP would give U.S. businesses of all sizes a significant advantage by connecting them to this growing consumer base. It would also increase the competitiveness of U.S. exports to the Asia Pacific relative to China’s. Failing to pass TPP would be a huge missed opportunity for all U.S. exporters, especially small business.