Insight

March 9, 2021

The Small Business Investment Company Program: A Primer

Executive Summary

- Over 60 years, the Small Business Administration has provided nearly $70 billion through 166,000 investments to America’s small businesses, including financing for Apple, Intel, and Tesla.

- Licensed Small Business Investment Companies (SBICs) have access to a rapid deployment of funds and a flexible fund structure at generous interest rates in addition to favorable legal treatment under a bevy of laws from Dodd-Frank to the Community Reinvestment Act.

- While comparatively small in scale, the SBIC program is one of the best examples of public-private partnerships, matching government funding with experienced investors solely for the purposes of supporting America’s small businesses.

Context

On March 25, 2020, Congress passed the “Phase 3” stimulus package, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. With an estimated $2 trillion price tag, the third package would be one of the largest and most significant stimulus packages in American history. As part of this $2 trillion, Congress set aside $349 billion for the relief of small businesses, to be administered by the Small Business Administration (SBA) in the form of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP). In the year since, the SBA has disbursed $663 billion in forgivable loans to eligible businesses.

The PPP is not the only tool available to the SBA, however, and as Congress considers a fifth legislative package attention has focused on a less prominent SBA program – the Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) program. Over its lifetime the SBIC has distributed more than $67 billion in capital through 166,000 investments in small businesses. This total is, of course, far smaller than the capital deployed via the PPP in far less time, but what makes the SBIC interesting is its structure as a fund-of-funds or investment program, in contrast to the forgivable loan mechanics of PPP loans.

While the PPP has been an extraordinarily effective in stabilizing a pandemic economy and keeping small businesses afloat, it is not above criticism. As Congress considers a fifth legislative package, and if further investment in small businesses is necessary, lawmakers could consider instead the benefits that supplementing the SBIC program could provide.

History

The SBA was formed in 1953 with the signing of the Small Business Act by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to “aid, counsel, assist and protect, insofar as is possible, the interests of small business concerns.” As a key element to this mission, in 1958 the SBA launched the SBIC program and began licensing SBICs. The SBA provided financing (known as leverage) to its SBICs via the issuance of unsecured loans (known as debentures), and these SBICs would then make investments in small businesses they thought had potential for growth. Most initial SBICs in the 1960s, largely focused on real estate, were commercially unsuccessful and run by individuals without significant investment experience. In the 1970s, however, 300-500 SBICs were in operation, considerably more successfully, and in many ways defined the venture capital industry. Cripplingly high interest rates in the 1980s, however, demonstrated the problems of providing long-term financing using current-value debentures. That, coupled with restrictions on the maximum size of an investment (more accurately, a maximum leverage which the SBA would provide an SBIC) caused a decline in the relevance of the program over the next two decades, and by 1990 there were only 180 SBICs in operation. Over this same period the wider investment industry came to be defined by large venture capital firms, with pension funds as a ready supply of capital to these funds, rather than by SBICs and the SBA.

The SBA reviewed the performance of its SBICs in 1991, and in 1992 Congress passed the Small Business Equity Enhancement Act, completely overhauling the program and creating a new mechanism by which the SBA could invest funds through SBICs, the Participating Securities Program. Instead of an unsecured loan, the SBA instead entered a “preferred limited partnership interest” with SBICs with a guaranteed rate of return. Unlike the Debenture Program, which required SBICs to make periodic interest payments, the Participating Securities Program was constructed to require SBICs to pay the SBA a preferred return and profit share only when the SBIC realized profits. By allowing an SBIC to make investments in businesses that might not yet have cashflow, the SBA promoted a significant expansion of and interest in SBICs. The Act also raised the leverage available to an SBIC to $90 million, allowing SBICs to better compete with venture capital firms. For the first time the SBA also implemented a regulation framework consistent with the private venture capital industry and required SBICs to invest a minimum level of private capital. Despite this renewed flexibility, following the collapse of the “dot-com bubble” the Bush Administration decided that there was no need for an SBA equity investment program and that the existing program posed too much risk; the SBA closed the Participating Securities program in 2002.

Firms that benefited from SBIC investment in their early stages include Apple, Costco, Federal Express, Intel, Tesla, and Whole Foods.

Mechanics and Requirements

After its departure from equity investment, the SBA today provides leveraged financing in only one form, its Debenture Program. For every $1 the SBIC raises in private capital, the SBA will commit $2 of debt, up to a cap of $175 million. In this manner an SBIC with $50 million in private capital available can access up to $100 million in SBIC leverage, allowing them to invest $150 million in qualifying small businesses.

SBIC investments can be made in a variety of ways, from “straight” debt with no equity features (Loans), debt with equity features (Debt Securities) or stock and partnership interests (Equity Securities), or any combination of the above, with the interest rate charged by the SBA dependent on the type of investment. Investments must have a term of at least a year, but interest rates are priced extremely favorably by comparison to the market. In 2019, for example, $991 million of debentures issued by 63 SBICs were priced at a 2.283 percent interest rate, a 46.1 basis point improvement on the then 10-year Treasury note rate of 1.822 percent, and far less than the 5 percent interest rates banks typically charge when serving as lenders to small businesses.

An SBIC can only invest in “Small Businesses” and must invest at least 25 percent of funds in “Smaller Enterprises” per the SBA standard definitions, which vary by industry. SBICs are prohibited from investing in certain types of small business, most notably those using the proceeds or with payroll or operations based outside of the United States (but also including many real estate projects, perhaps a lesson learned from the 1960s).

Favorable Legal Treatment

While the SBA today provides only one kind of financing, there exist two forms of SBIC, as some SBICs do not receive SBA financing at all. Known as non-leveraged SBICs (or frequently bank-owned SBICs) these firms operate entirely in the same manner as traditional investment companies, providing a wide range of debt and equity investment. What makes non-leveraged SBICs special is the same requirement that, to be licensed by the SBA, these SBICs make investments only in qualifying small businesses. In return these non-leveraged SBICs receive favorable legal treatment. SBIC investments are specifically identified in SBA statute as “qualified investments” for Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) purposes, a 1977 law designed to promote financial inclusion by requiring banks to provide services to low- and middle-income communities. SBIC investments also receive favorable treatment when calculating a bank’s regulatory capital requirements, as below a certain level SBIC investments do not incur a capital charge. Finally, SBIC investments are exempt from Dodd-Frank requirements preventing banks from obtaining ownership interests in private equity firms, and SBICs are exempt from Volcker rule requirements preventing banks from investing in SBICs. These exemptions make SBICs extremely attractive to banks needing to meet their regulatory, capital, and investment requirements, all but guaranteeing a steady flow of private capital to SBICs. Similarly, certain SBIC advisers are exempt from provisions of the 1940 Investment Advisers Act that would otherwise require advisers of private funds to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

Non-leveraged SBICs are themselves exempt from many of the SBA requirements that govern Debenture SBICs, most of them operational: from management-ownership diversity requirements, prohibiting a single investor from owning over 70 percent of an SBIC; the ability to sell assets without SBA permission; and recordkeeping requirements, explaining why some SBICs may prefer to not receive SBA financing and yet obtain the SBIC license.

Economics

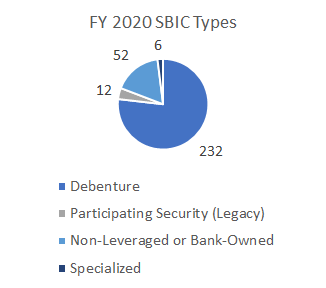

As of September 30, 2020, there were 302 licensed SBICs holding $19 billion in private capital and $11 billion of outstanding SBA leverage. For the same year these SBICs reported $5 billion in financing to just over 1,000 small businesses, creating or supporting an estimated 92,000 jobs. During this period the SBA licensed 26 new SBICs, 21 equipped for Debenture financing and five non-leveraged, with another 46 SBICs in the review pipeline.

Conclusions

For over 60 years the SBA has provided financing to hundreds of licensed investment companies investing in thousands of American small businesses. While $67 billion over this period is small by comparison to the $679 billion disbursed to date by the PPP, the SBIC has many attractive features to consider. While the SBA is prescriptive in setting out the targets for SBIC investments, and applies careful scrutiny and oversight of its licensees, it is no more involved than that (outside of the provision of financing!). Investment managers with decades of experience, and not government, determine who to invest in, and they do so with real skin in the game with the requirement to front private capital. While interest rate and loan terms are extremely generous, they are still tethered to a market reality. Given the small scale of the SBIC, and the long-term nature of SBIC investments, it is hard to imagine a role for the SBIC in pandemic-related rescue efforts, and the PPP has performed admirably in injecting billions into the sector in very short order. A temporary shot of adrenaline is no substitute, however, for long-term support by professionals, and the SBIC represents one of the most successful public-private partnerships in U.S. history.