Insight

July 20, 2016

Six Years After Dodd-Frank: Higher Costs, Uncertain Benefits

Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act six years ago in an attempt to address the causes of the financial crisis. The law has imposed billions of dollars in costs with unclear benefits. Regulators have least 61 regulations remaining to finish implementing the law. According to American Action Forum (AAF) research, Dodd-Frank has imposed more than $36 billion in final rule costs and 73 million paperwork hours, up from $24 billion in final rule costs and 61 million paperwork burden hours from last year’s report. To put those figures in perspective, the costs are approximately $112 per person or $310 per household; for paperwork, it would take 36,950 employees working full-time (2,000 hours annually) to complete a single year of the law’s paperwork, and those are based on agency calculations.

In recent research, AAF even found the law had resulted in a 14.5 percent decline in revolving consumer credit. From a housing market still experiencing mediocre growth, to an uneven labor picture, to significant consumer impacts, it’s clear the law has fundamentally altered capital markets and added layers of complexity for individuals and financial institutions.

What’s Left for Dodd-Frank?

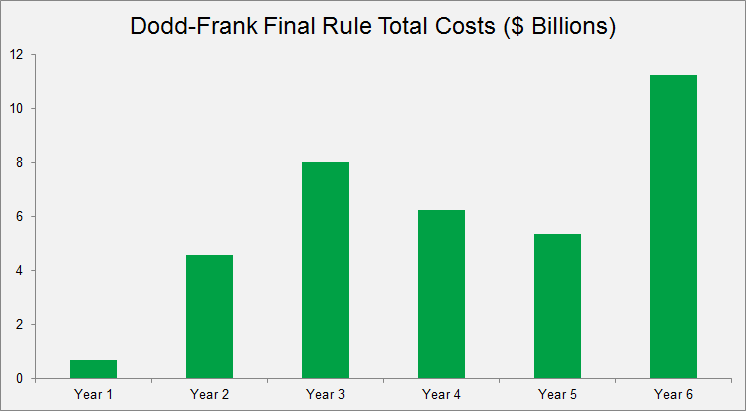

The law has imposed tremendous costs, but the height of those impositions might not be in the past. The following chart examines rulemaking costs by year, from July 21, 2010, when Dodd-Frank was passed, to each year since.

At one point, Year 3 was clearly the high-water mark, but in the last twelve months a quartet of billion-dollar Dodd-Frank measures easily placed Year 6 as the most expensive in the law’s history. Below is a list of major Dodd-Frank measures from this past year and corresponding cost; they combined for $10.4 billion in total economic burdens:

- Margin and Capital Requirements for Swap Entities: $5.2 billion

- Margin Requirements for Unclear Swaps: $2.1 billion

- Pay Ratio Disclosure: $1.8 billion

- Home Mortgage Disclosure: $1.3 billion

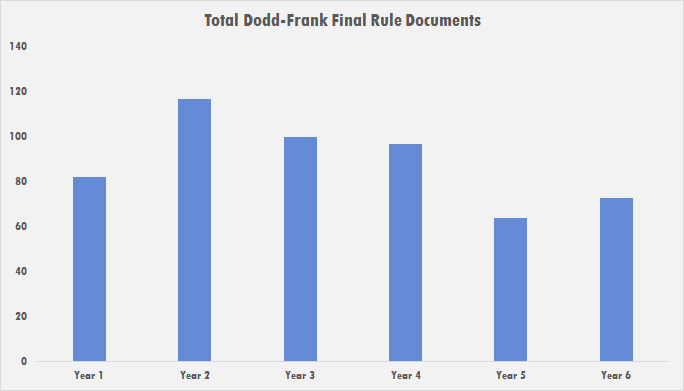

The next chart takes a broader view of the law, examining all final rule documents published in the Federal Register. It reveals a steady decline of activity after years two and three. Dodd-Frank has already produced 533 final rule documents, although this figure does not mean the law has imposed 533 prescriptive final rules.

Much of the law has already been implemented, but there are still at least 61 rulemakings remaining, according to the most recent Unified Agenda. Davis-Polk, a law firm that tracks the law, has stopped producing updates on the progress of Dodd-Frank, but there are still many clues in the Unified Agenda and Federal Register for the remaining future of the law.

The table below highlights the largest rules still in proposed form. These are recent measures that could be finalized soon. Combined, they could add another $3.3 billion to the law’s tally and nearly one million paperwork hours.

| Regulation | Cost (in millions) | Paperwork Hours |

| Requirements for SIFIs | $1,500 | 23 |

| Resource Extraction Issuers | $1,300 | 242,321 |

| Arbitration Agreements | $379.9 | 500 |

| Security-Based Swap Repositories | $104.1 | 676,725 |

| Data Obtained by Swap Repositories | $103.8 | 36,120 |

| Totals: | $3,387 | 955,689 |

The largest rulemaking on the list, Requirements for Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs) was proposed last year by the Federal Reserve. At $1.5 billion in annual costs, it would add to the growing list, (more than 25) of billion-dollar regulations President Obama and his regulators have issued. Promulgated under section 165 of Dodd-Frank, the proposal aims to improve capital standards at the largest, interconnected, financial institutions. “Further action” on the rulemaking is scheduled for December 2016.

The second rule, “Disclosure of Payments by Resource Extraction Issuers,” is the latest iteration of a rulemaking from the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC); federal courts struck down the previous version. The proposal once again requires companies to provide information on payments to foreign governments and corporations on the commercial development of oil, natural gas, or minerals. SEC expected to finish the rulemaking by June of 2016, but has obviously not met this self-imposed deadline.

The arbitration agreements measure has generated significant controversy since the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) first proposed banning arbitration agreements from certain consumer financial products on May 24, 2016. Because the rulemaking is still under comment, there is no timeline for a final rule.

The SEC proposal on Security-Based Swap Repositories was first proposed last December and the benefit-cost analysis estimates slightly more than $104 million in costs or roughly $127,000 per repository. This is in addition to the more than 676,000 paperwork burden hours from the regulation. SEC expects final action by April of 2017.

Finally, the SEC’s other swap repository rule would impose new recordkeeping and reporting requirements on repositories to share certain data with regulators. A large portion of the costs stem from establishing systems and databases to allow direct access to SEC employees, and their designees, to monitor swap information. The Commission estimates a final rule by April of 2017.

Looking forward, the Unified Agenda of federal rulemakings lists 61 measures in the prerule, proposed, or final rule stage that are directly related to Dodd-Frank. Below are highlights from this list and their expected publication dates.

| Rule | Expected Publication Date |

| Incentive-Based Compensation Agreements | May 2016 |

| Annual Stress Test | May 2016 |

| Clearing Requirement | May 2016 |

| CFPB’s Arbitration Rule | May 2016 |

| Margin Requirements for Swap Entities | May 2016 |

| Incentive Compensation | May 2016 |

| Resource Extraction Issuers | June 2016 |

| Amendments to Regulations X and Z | July 2016 |

| Regulatory Capital Rules | October 2016 |

| Reporting of Proxy Votes | April 2017 |

| End-User Exception | April 2017 |

| Stress Tests for Large Investment Firms | April 2017 |

| Pay Versus Performance | April 2017 |

| Disclosure of Hedging by Officers and Directors | May 2017 |

| Covered Broker Dealer Provisions | N/A |

It is perhaps noteworthy that many of these dates are aspirational and not exact. Some of these timelines are well in the past and although rulemakings can proceed through the process quickly, many complicated Dodd-Frank measures often take years to finalize.

Ending Too Big to Fail?

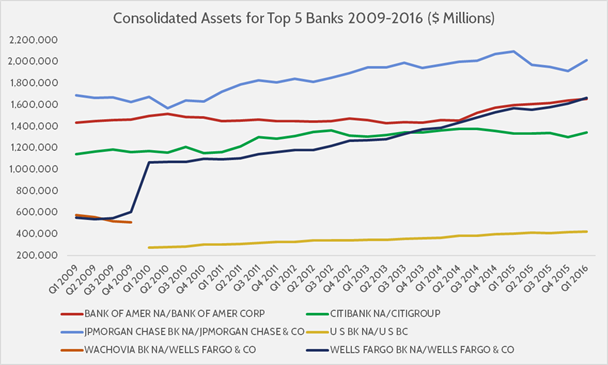

One of Dodd-Frank’s key objectives was to mitigate the phenomenon known as “Too Big to Fail” (TBTF). Part of the issue with TBTF institutions arises from three issues: how much of the overall banking market large institutions control, moral hazard, and contagion. As others have noted in recent years, the TBTF issue seems largely unresolved. For instance, the graph below shows modest, yet steady, growth among the largest five commercial banks in the country according to Federal Reserve data.

*Wachovia merged with Wells Fargo in 2010.

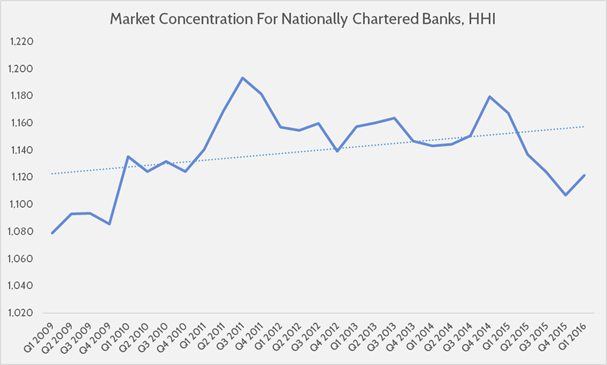

However, it is not the issue of absolute growth in the abstract that matters – certainly stockholders and depositors appreciate a growing firm – but rather how that growth affects the market’s structure. The top five banks among the nation’s large commercial institutions have accounted for a majority of that market in 13 of the 23 quarters in which Dodd-Frank has been law. Examining the market concentration even further, employing the Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI), data reveal that in recent years Dodd-Frank has likely contributed to a more concentrated banking sector.

Although Dodd-Frank may not be the only reason for this trend, it certainly appears to be a major contributing factor. One would expect that the Wells Fargo-Wachovia merger provided one of the most notable spikes in concentration. Yet, even after that, the graph shows market concentration at levels above that spike during most of the time since Dodd-Frank has been in effect (beginning with 2010’s third quarter). This trend and anecdotal evidence of banks changing their charter or business model suggests that Dodd-Frank has had impact on the banking industry’s market structure and concentration.

Conclusion

As Dodd-Frank reaches its sixth anniversary, it has imposed more than $36 billion in costs and 73 million paperwork burden hours. As time passes, the law becomes more expensive as regulatory agencies like CFPB and FHFA grow with the mission to implement burdensome rules. Meanwhile, small financial services firms continue to struggle as the law restricts the availability of financial products. With dozens of regulations still left to implement, one can only expect the costs to continue to rise.