Insight

November 24, 2020

Policy Interventions to Mitigate External Risk Factors that Contribute to Chronic Disease

Executive Summary

- Numerous external, community-level factors that affect a person’s health are largely outside of an individual’s control, such as exposure to pollutants, access to nutritious foods, access to quality health care, and the safety and social supports of the surrounding community.

- Similar to more personal socioeconomic factors affecting an individual’s health, many of these external and community-level factors are highly correlated with one another as well as with income.

- Given the high prevalence and cost associated with chronic disease, policymakers should seek to mitigate these known risk factors.

Introduction

Many factors impact an individual’s likelihood of developing a chronic disease.[1] Previous American Action Forum research explored the relationship between chronic disease and individual-level determinants such as education, income, and family history, as well as potential policy interventions to mitigate those risks. This piece highlights the impact of factors that exist at the community level—such as exposure to pollutants, access to health care and nutritious food, and community dynamics—and offers ideas for policy interventions that could be adopted to alleviate these risk factors.

Many of these factors are related to income, such as the ability to afford valuable goods and services or to live in a safe area with greater access to those resources. In fact, adults living at the federal poverty level are over five times more likely to report health issues than those with incomes at least four times the federal poverty level.[2] As a general proposition, therefore, improving the earning power of individuals will mitigate against external factors that can contribute to chronic disease. That said, income alone cannot solve these issues; this paper explores these risk factors beyond the impact of income and affordability.

External Risk Factors and Policy Interventions to Mitigate Such Risks

Access to Nutritious Food

Health experts agree that nutrition plays a vital role in an individual’s health and the likelihood of developing a chronic disease.[3] Diets directly affect the risk of obesity, a chronic disease that can exacerbate or increase the likelihood of other chronic diseases. Nutrition also affects the ability to learn and focus in school, and success in school also influences the risk of chronic disease.

Affordability

Consumption of fresh produce is an essential aspect of receiving adequate nutrition.[4] The relatively high price of fresh food versus processed foods and the prevalence of food deserts in the United States reduce access for many Americans.

The kinds of food available to children can have longstanding effects, as well: As a result of the food options made available to them, children growing up in low-income households often develop poor eating habits that may persist into adulthood and can severely impact their health.

Distance

Food deserts are generally defined as geographic areas where the inhabitants do not have sufficient access to affordable, healthy food due to the absence or limited number of stores that have it within a reasonable traveling distance.[5] Wealthy neighborhoods, which are typically highly populated by White households, tend to have significantly more grocery stores than poor neighborhoods, which are more likely to be populated by minorities.[6] The distance people need to travel to obtain healthy food directly impacts consumption, particularly of produce.

Policy Interventions to Improve Access to Nutritious Food

Improving access to nutritious foods is likely one of the most important policy interventions for improving people’s health given the direct connection between nutrition and obesity, which is a primary risk factor for many of the leading causes of deaths, including heart disease, cancer, and stroke.[7] One of the most effective ways to increase access to nutritious foods is to make healthy food more affordable. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program provide financial subsidies to low-income families for the purchase of certain food items. The School Breakfast Program and School Lunch Program help ensure children have access to food meeting certain nutritional requirements while at school by providing free or reduced-cost meals to students, based on family income.[8]

There are, however, restrictions on existing federal nutrition subsidies that may be worth reviewing—both SNAP and WIC restrict who is eligible and what may be purchased. If the long-term health consequences that result from poor nutrition are greater and more costly than the immediate savings gained from limiting access to SNAP benefits—as one study has suggested may be true—then changes should be made.[9] Further, the inability to use SNAP benefits for hot or prepared foods for immediate consumption makes it difficult for homeless individuals—who are much more susceptible to a number of chronic diseases, particularly those that are especially correlated with nutrition, such as diabetes and hypertension—to use their benefits, as they are less likely to have a place to cook.[10]

Studies have also shown structural barriers—such as the inability to get an appointment to enroll, whether because of the inability to get time off work, find childcare, or find transportation—may reduce participation in subsidy programs among eligible beneficiaries. Reducing these barriers could increase benefit use.[11] Bringing healthy food closer to people is also important. Recent localized efforts, such as the Green Grocer mobile farmer’s market run by the non-profit Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, have shown that bringing fresh produce to people living in food deserts increases fruit and vegetable consumption.[12] Pennsylvania also had success with its Fresh Food Financing Initiative—a public-private partnership that provided grants and loans to food providers to establish permanent grocery stores and increase fresh food availability in low-income areas.[13] Programs modeled on these initiatives could be an important step in expanding access to fresh food across the country.

Health insurers, including Medicare and Medicaid, have recognized the importance of nutrition and begun covering sessions with nutrition coaches and rides to the grocery store as a result.[14] Expanding on these efforts may be worthwhile, particularly for low-income and elderly beneficiaries.

Access to Quality Health Care

Access to quality health care can affect an individual’s awareness and control of an existing chronic disease or chronic disease risk.[15] Access can be characterized by the degree to which someone can afford quality health care and the geographical distance between the place of residence and quality health services.

Affordability

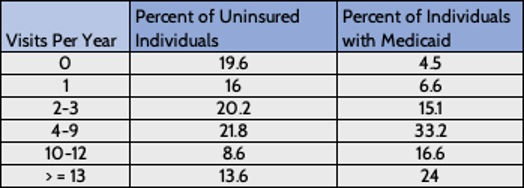

Insurance is a key component of affordability. A lack of insurance is associated with lower rates of preventative care, delays in care, forgone care, medical bankruptcy, and increased mortality.[16] The table below shows how an individual’s lack of insurance tends to reduce their use of health care. Ironically, limiting care in the short term can lead to such poor health that many visits are needed later. While income is indicative of an ability to afford health care and health insurance, health care costs are high and increasingly unaffordable for even middle-class Americans, as health care prices have been rising faster than wages.[17]

Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695932/

Distance

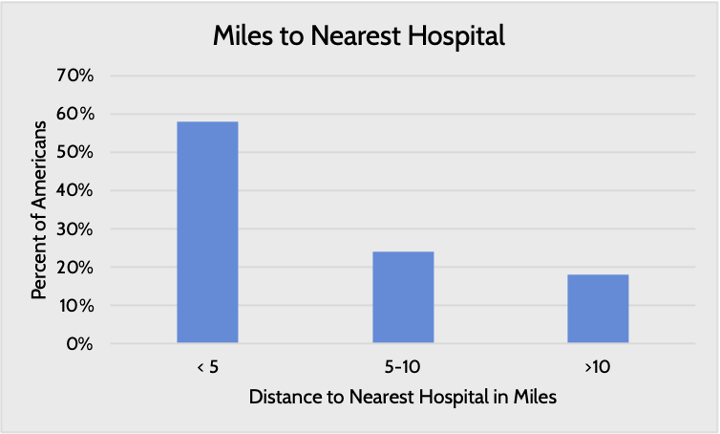

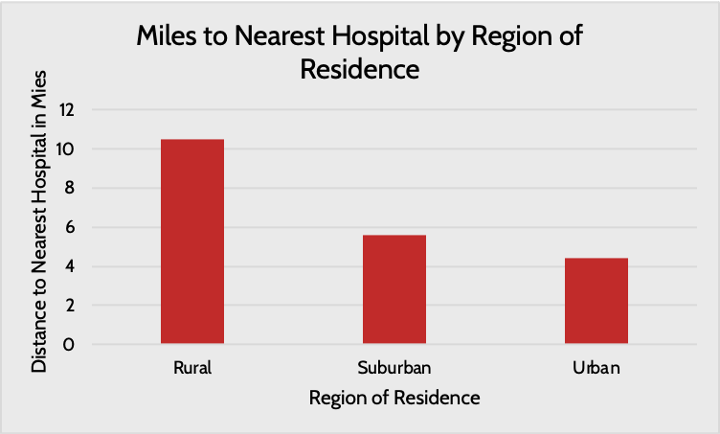

The distance to the nearest health provider varies by the region and income level of the residential area. Nearly 20 percent of Americans live more than 10 miles away from their nearest hospital. Large swaths of the country are designated as health-professional shortage areas, whether for primary care, dental care, or mental health care.[18] Poor areas, where residents are often less healthy than in wealthier areas, are more likely to face physician shortages and closed hospitals.[19]

Source: Pew

Further, the types of hospitals people have access to vary: People living in rural areas typically do not have access to academic research hospitals providing cutting-edge care, and the limited resources available in rural settings often make it difficult to provide high quality care.[20] A lack of access to specialists in rural areas is a key challenge.[21]

Poor areas, where residents are often less healthy than in wealthier areas, are more likely to face physician shortages and closed hospitals.[22] As a result, individuals living in these areas either do not seek medical help or do so in inefficient ways.

Policy Interventions to Improve Health Care Access

Improving access to health care requires increasing the number of providers as well as making care more affordable. To improve the affordability of health care, reductions are needed in the cost of care, which will in turn increase the affordability of health insurance. Increasing competition among providers is critical; study after study has shown that increased provider consolidation is highly correlated with significantly higher costs.[23] Given the numerous policies and regulations that have encouraged such consolidation, a good place to start would be to unravel some of these regulations.[24] To increase provider access, greater incentives may be needed to encourage providers to practice in more rural areas and to pursue more generalized medicine, rather than specializing.[25] Increased access to and use of telehealth services can also help patients more easily access providers, particularly people in rural areas needing access to specialists. Nevertheless, there are still physician shortages nationwide that will make it impossible to fill this need solely through telehealth.[26]

Pollution

Pollution of natural resources such as water and air has damaging impacts on health. Scientists have drawn links between toxic substances and neurocognitive impairment, vascular disease, obesity, and, most often, cancer.[27] Additionally, exposure to just the mean amount of air pollution in the United States has been shown to increase the risk of Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and related dementias.[28] Pollutants enter the environment in a variety of ways and have a multitude of sources, such as from manufacturing processes, agricultural development, and chemicals used in cosmetic and other household products.

Low-income individuals are more at risk of these kinds of exposures due to the environments in which they live and the nature of their employment. To be sure, as shown by the chart below, not all low-income individuals are equally at-risk of exposure to pollutants. Some high-poverty areas have relatively high numbers of good quality air days, particularly more rural areas where there is less industry. Other rural areas, however, have relatively poor air quality, which results from agricultural activity, wildfires, and downwind effects from more industrialized areas.[29]

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau, EPA

Policy Interventions to Reduce Pollution

Negative externalities such as environmental pollution typically require government intervention to maximize efficiencies and reduce social costs. While the United States has imposed numerous environmental regulations, there is room for further action. Water pollution crises in several cities over the past several years have shown how enforcement of existing regulations has failed.[30] Regulation of ingredients in cosmetic and personal care products significantly lags that of other developed countries, many of which have banned over a thousand more chemicals in consumer products than the United States because of health concerns.[31] Greater enforcement of existing regulations and enhanced authority to regulate consumer products could significantly reduce Americans’ exposure to harmful chemicals.

Public Safety and Community Dynamics

Safety impacts health in direct and indirect ways. Being exposed to violence brings potential life-long health issues, particularly when the exposure occurs at a young age. This cycle of violence often devastates communities.

Beyond direct exposure to violence, individuals’ fear of becoming a victim of it or simply not having strong connections within a community impacts their health by influencing their level of participation in both physical and social activities. Residents who don’t feel safe in their communities are less likely to form meaningful relationships with other community members, increasing the risk of isolation, which has been shown to increase the risk of almost every chronic disease.[32] People who perceive their communities as unsafe also engage in less physical activity.[33] All of these effects are more likely to be felt by low-income communities, as crime rates are higher in these areas.[34] As a result, on top of the additional risk of chronic disease that low income poses, members of these communities are subject to the negative health consequences of unsafe neighborhoods as well.

The phrase “community dynamics” refers to the social cohesion and culture of a community. Many behaviors related to health—healthy eating, substance use, physical exercise—are influenced by peers. Studies show that members of tight-knit communities are more likely to take care of one another by, for example, encouraging physical activity, providing information regarding support services, and reducing the isolation that can lead to depression, all of which contribute to improved health.[35]

Policy Interventions to Improve Community Dynamics and Safety

There are numerous policies that can be implemented to improve the safety of a neighborhood. For years, scholars have written about the importance of crime prevention through environmental design principles that aim to increase natural surveillance and access control, reinforce both private and public territorial ownership, and increase a community’s sense of “pride of place” through management and maintenance of the community.[36] These design and management techniques help people to feel a sense of ownership and pride in their community, making them more likely to look out for one another and give would-be intruders and criminals fewer opportunities to engage in unwanted behavior. Numerous studies have also shown that adopting strategies of community policing, in which the police more regularly engage with the community apart from instances of criminal activity, leads to more community trust and fewer violent crimes.[37] Other opportunities for police reform, as described here, could improve the wellbeing of individuals suffering from mental health issues and substance abuse.[38]

To improve community dynamics, municipalities can increase the number of safe public spaces, such as parks and playgrounds, and the quality of amenities available, such as exercise equipment or places to play games. Additional greenery, sidewalks, and bike lanes all encourage people to get outside and to use more physically engaging and environmentally friendly modes of transportation, such as walking or biking. City-wide events can also help to build community connections; examples include fairs, festivals, movies in the park, and concerts.[39] Institutional representation is also important in fostering positive community dynamics. When members of the community feel well represented in political leadership, in the police force, in the staff of city services offices, in the education system, and in the health care providers in their community, they are more likely to engage and follow guidelines and recommendations from authoritative figures in the community, and the community’s unique needs are more likely to be met.[40]

Transportation

Modes of transportation can affect how easily and, ultimately, how frequently an individual can seek health care, as well as access other things that impact an individual’s health: good nutrition, a job, and education. Lack of access to reliable, affordable transportation can lead to rescheduled or missed appointments, delayed care, and missed or delayed medication use.[41] Missed or delayed care can exacerbate pre-existing chronic conditions, prevent the proper diagnosis and treatment of new diseases, or indirectly contribute to the development of new diseases by allowing others to go untreated. These effects can be especially pronounced in rural areas where public transportation may not be available. Further, a lack of reliable transportation makes it more difficult to acquire groceries, and while reliable public transportation is better than nothing, it is difficult to haul more than a few days’ worth of groceries on the bus or subway, making access to a car more valuable. Cars, however, are often expensive (and often impractical in urban areas), and further, some may be unable to drive as a result of prior offenses.[42] People also need reliable transportation to school or work, as being stranded is likely to hinder people’s ability to succeed in either, while both are important contributors to health.

Policy Interventions to Improve Transportation Access

Improving the ability to get to a health care provider can improve the likelihood of timely diagnoses and the receipt of necessary care. More widespread public transportation would certainly be helpful but may not be financially feasible. Some rural areas are adopting alternative models, such as coordinated services and mobility on demand, which rely on technology, such as location tracking and route optimization, to better assess demand and fill in gaps in services.[43] Health insurers, including Medicaid Managed Care Organizations and Medicare Advantage plans, have partnered with ride-sharing companies to provide transportation to and from doctors’ appointments in recognition of the challenges faced by so many patients.[44] Another option is to bring health care services to the patients. Mobile clinics, school- and workplace-based clinics, telehealth services, and home visiting programs are all options to overcome patient mobility barriers.

Conclusion

Community-level risk factors are often rooted in individual-level factors: education, income, race, mental health, lifestyle, and family history. This analysis further explores the intersections among chronic disease risk factors, particularly those factors that are outside of an individual’s control. There is a notable correlation between income and external factors, and this correlation is a key reason why the difference in chronic disease prevalence between high-income and low-income individuals is so stark. The many underlying factors associated with low incomes—limited access to health care, lower rates of education, poor nutrition, less safety, and other systemic issues—help drive this phenomenon.

In recognition of the impact of these risk factors, health insurers across the country, including Medicaid and Medicare, are investing in their enrollees’ social determinants of health. But health insurers will not be able to achieve the changes needed on their own. Those who are suffering the most need bottom-up interventions across the policy spectrum to reduce their risk of developing chronic disease. Access to appropriate health care, healthy foods, safe environments, and more are all essential to individual health.

[1] https://www.goinvo.com/vision/determinants-of-health/

[2] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5171223/

[3] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0271531718302227

[4] https://www.choosemyplate.gov/eathealthy/vegetables/vegetables-nutrients-health

[5] https://foodispower.org/access-health/food-deserts/

[6] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3794652/

[7] https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/adult/causes.html

[8] https://www.fns.usda.gov/sbp/fact-sheet, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/child-nutrition-programs/national-school-lunch-program/

[9] Https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302990

[10] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218236/, https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligible-food-items

[11] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5527844/

[12] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6301430/

[13] https://www.reinvestment.com/success-story/pennsylvania-fresh-food-financing-initiative/

[14] https://www.phillytrib.com/lifestyle/health/millions-of-diabetes-patients-are-missing-out-on-medicare-s-nutrition-help/article_80f46beb-c88f-5b2a-a9e7-1bc2a7974a2d.html

[15] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695932/

[16] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4695932/

[17] https://www.brookings.edu/research/a-dozen-facts-about-the-economics-of-the-u-s-health-care-system/, https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.89, https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/tracking-the-rise-in-premium-contributions-and-cost-sharing-for-families-with-large-employer-coverage/

[18] https://data.hrsa.gov/maps/map-gallery

[19] https://newsinteractive.post-gazette.com/longform/stories/poorhealth/1/

[20] https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/health-care-quality, https://rhrc.umn.edu/publication/rural-urban-differences-in-medicare-quality-scores-persist-after-adjusting-for-sociodemographic-and-environmental-characteristics/

[21] https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/12/191203160602.htm

[22] https://newsinteractive.post-gazette.com/longform/stories/poorhealth/1/

[23] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/hospital-markets-and-the-effects-of-consolidation/

[24] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/340bmarketdistortions/

[25] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5828896/

[26] https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/us-physician-shortage-growing

[27] https://www.who.int/airpollution/ambient/health-impacts/en/,

https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jeph/2012/356798/, https://www.env-health.org/IMG/pdf/110913_HEAL_fact_sheet_-_Chronic_disease_and_environment-final.pdf,

https://are.berkeley.edu/~mlanderson/pdf/air_pollution_highways.pdf

[28] https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30227-8/fulltext

[29] https://www.earth.columbia.edu/articles/view/3281, https://www.epa.gov/air-research/wildland-fire-research-health-effects-research, https://www.epa.gov/interstate-air-pollution-transport/what-interstate-air-pollution-transport

[30] https://emagazine.com/the-continuation-of-the-flint-water-crisis/

[31] https://www.ewg.org/news-and-analysis/2019/03/cosmetics-safety-us-trails-more-40-nations

[32] https://www.ca-ilg.org/health-public-safety

[33] https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/crime-and-violence

[34] https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health/interventions-resources/crime-and-violence, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/incarceration-and-poverty-in-the-united-states/

[35] https://www.lisc.org/media/filer_public/3c/12/3c122f2a-41e1-4233-9d68-e5989be210b6/healthassessmentreport_final_shrunk.pdf, https://scopeblog.stanford.edu/2011/06/16/community-dynamics-play-an-essential-role-in-fighting-obesity/

[36] https://rems.ed.gov/docs/Mobile_docs/CPTED-Guidebook.pdf

[37] https://pioneerinstitute.org/better_government/community-policing-success-story/, https://www.pnas.org/content/116/40/19894, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/02673843.2019.1601115

[38] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/opportunities-for-police-reform/

[39] https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/community-engagement-and-community-cohesion

[40] https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/community-engagement-and-community-cohesion

[41] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4265215/

[42] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/the-implications-of-relying-on-monetary-penalties-in-the-u-s-criminal-justice-system/

[43] https://www.norc.org/PDFs/Walsh%20Center/Rural%20Evaluation%20Briefs/Rural%20Evaluation%20Brief_April2018.pdf

[44] https://shelterforce.org/2020/01/10/using-ride-hailing-services-to-get-patients-to-their-doctors/