Insight

September 20, 2016

IPAB: Not the Solution to Health Care Spending Growth

Executive Summary

Aware of the unsustainability of rising health care spending, policymakers have sought to implement myriad policies and programs aimed at reducing such spending growth. One such attempt is the Independent Payment Advisory Board (IPAB) authorized under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to make changes to the Medicare program, when certain conditions are met, in order to achieve budgetary savings. However, the restrictions imposed on IPAB leave it little authority to make changes except to Medicare Advantage (MA) and Part D—the only parts of Medicare that necessarily must work to improve care and reduce costs because of their competitive nature—or to fee-for-service provider reimbursement rates, which would likely restrict access to care. IPAB is not likely to be successful in sustainably reducing health care costs without having harmful effects on Medicare beneficiaries.

Background

IPAB was established by Section 3403 of the ACA in an effort to “reduce the per capita rate of growth in Medicare spending”—but not to actually reduce Medicare expenditures. The Board has not yet been appointed, but if and when it is, it would consist of 15 members—3 chosen exclusively by the president and the other 12 chosen in consultation with the majority and minority leaders of both the House and Senate; all ultimately must be confirmed by the Senate (unless the president makes recess appointments). In the event that the IPAB is required to act but is not appointed, does not have a quorum, or fails to submit a proposal by its deadline, the Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) is vested with all the powers the IPAB would otherwise have and must then submit a proposal of his or her own. In either case, the Secretary is to automatically implement the Board’s (or in its absence, the Secretary’s own) proposals unless Congress passes, and the president signs, legislation to block such proposals. Thus, the “Advisory Board” has much more authority than a typical “advisory” panel – and perhaps even more authority than Congress itself, since its actions are not subject to presidential veto. In addition, the ACA specifies that “there shall be no administrative or judicial review” of IPAB decisions.

Scope of Authority

While the law does not prescribe specific actions for the Board to take, it does set some parameters for what the proposals may and may not contain, and who and what the proposals may impact. Further, IPAB is specifically instructed to primarily consider proposals which would extend the solvency of the Medicare Trust Funds. IPAB’s proposals are supposed to improve health care delivery and outcomes; protect and improve beneficiaries’ access to necessary and evidence-based practices; and focus on areas of excess cost growth. IPAB is also instructed to consider the impact any changes in provider payments may have on beneficiaries; providers already scheduled to receive a payment reduction through another provision of the ACA cannot be assigned further reductions by the IPAB until 2020.[i]

IPAB may not recommend proposals that would “ration care, raise revenues, increase Medicare beneficiary premiums … [or] cost-sharing, or otherwise restrict benefits, or modify eligibility criteria.”[ii] However, key terms such as “ration care” and “restrict benefits” are undefined in the law, and are subject to alternate interpretations. Of course, it is unclear how these restrictions could be enforced, because of the law’s prohibition on administrative and judicial review—though these prohibitions would likely be challenged and defeated in court.

If these restrictions are followed, there are few areas left for IPAB to change, and as such these few areas will be likely targets. Of particular concern is IPAB’s authority, and the statute’s explicit imperative, to consider reductions to MA or Part D payments, including MA performance bonuses, and by denying high bids or removing them from the calculation of national averages for purposes of determining the benchmark for Part D plans. MA and Part D are the parts of the Medicare program which we should be bolstering, not undermining. They provide choice, benefits, and care coordination that the traditional fee-for-service programs (Parts A and B) do not. Reducing performance bonuses would be counterproductive to efforts across the health care industry to improve the quality of care. Denying or removing high bids from the calculation of the Part D benchmark weakens the competitive nature of the program which has made it so successful and could restrict plan choice to only those plans with limited coverage and benefits. Furthermore, Part D is the only component of Medicare to consistently spend below forecasts.[iii]

Another likely option for IPAB is provider and supplier reimbursement cuts, though as mentioned, the targets for such a provision are limited. Payment rates for hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, outpatient rehabilitation facilities, home health agencies, and hospice programs may not be reduced prior to 2020; this essentially leaves physician services. Consequences of such action would include stifled medical innovation—meaning fewer treatment options and slower medical advancement—and reduced access to care as providers and suppliers stop accepting Medicare. In addition, cutting physician payments could serve as a “back-door” way to actually cut benefits, by cutting reimbursements for certain disfavored services to levels so low that providers cannot afford to provide them. Further explanation of these consequences can be found here.

Potential Savings

The limitations and requirements written in the statute authorizing IPAB will make it difficult for the Board to achieve worthwhile, sustained savings without violating its statutory restrictions. Besides limiting how savings may be achieved, the statute also requires that specified savings be achieved in a single year, each year IPAB is triggered. This is not conducive to implementing effective, structural long-term changes. Further, IPAB is only triggered when per capita spending growth exceeds a certain target, as opposed to total Medicare spending growth.

In order to calculate the savings that need to be achieved (or not) each year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) Chief Actuary must determine whether, in two years, the projected per capita Medicare expenditures will exceed a pre-specified target.[iv] If the Chief Actuary determines (in a “determination year”) that the 5-year average per capita growth rate will exceed the 5-year average target growth rate in an “implementation year,” (two years after the determination year) then IPAB must act; otherwise, IPAB action is not triggered.[v] The Chief Actuary must establish an “applicable savings target” for the “implementation year” which is based on projected Medicare expenditures in the “proposal year” (the year between the determination year and the implementation year, when the proposal is due) and the “applicable percent”. The “applicable percent” for each year is the lesser of either the projected excess Medicare spending (expressed as a percentage of the difference between the projected per capita growth rate and the target growth rate; the same percentage used in the determination process) in the implementation year, or the percent set by statute which gradually increases from 0.5 percent in implementation year 2015 to 1.5 percent in 2018 and beyond. IPAB’s proposal(s) must achieve savings in the implementation year at least equal to the applicable savings target.

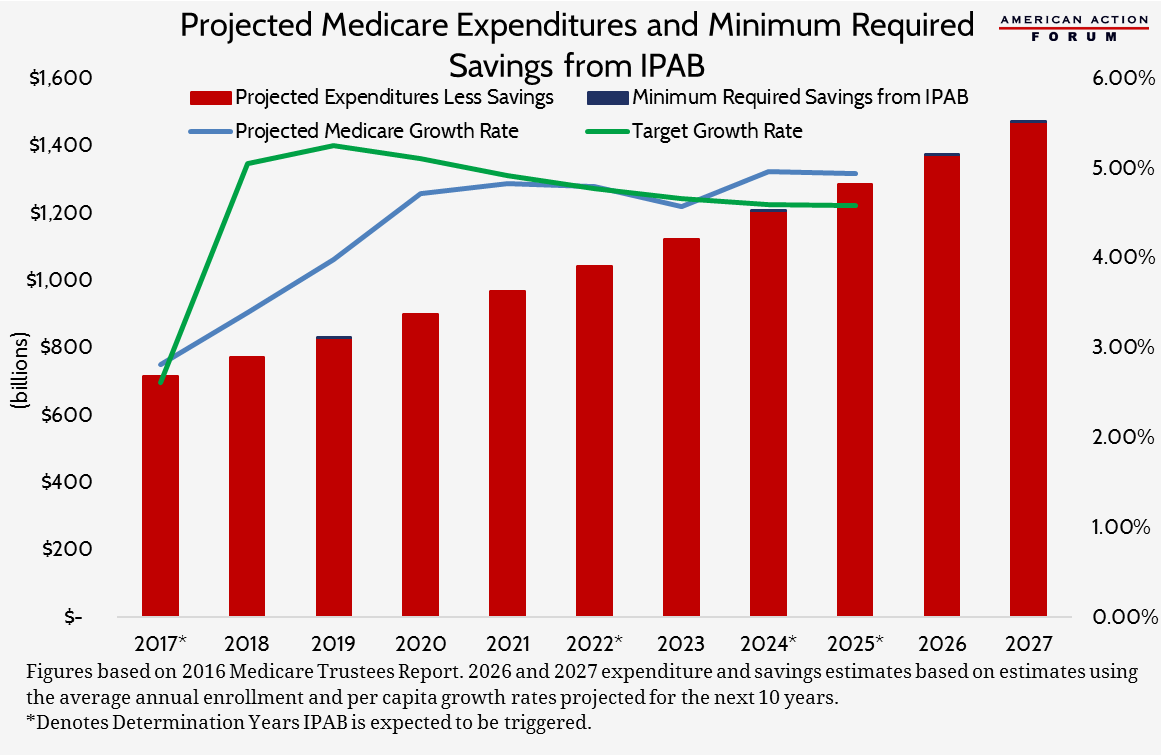

Over the 2016-2025 period, it is currently projected that IPAB will only be triggered in four years: 2017, 2022, 2024, and 2025. Given those estimates of Medicare expenditures, the minimum savings that must be achieved through IPAB proposals (based on the maximum applicable percent set by statute for each year) is $11.2 billion, or 0.09 percent of the $12.4 trillion that will be spent on Medicare between 2016 and 2027.

Results in Other Countries

Other countries have created similar programs or organizations to assist with reining in rising health care costs. The result has largely been the rationing of care either through actual restrictions or limits on services available, price controls, limited funding, or a combination of these things. Consequently, there have been increased mortality rates from illnesses affected by such services.[vi] Cancer survival rates in the United Kingdom are below the European average for breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, prostate cancer, and ovarian cancer, for which researchers suggest “delayed diagnosis, underuse of successful treatment, and unequal access to treatment” may be to blame.[vii] The National Health Service in Britain has been accused of, at the recommendation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), denying or limiting the use of expensive cancer treatments.[viii] NICE uses the value of a “quality-adjusted life year” (which they place at roughly £20,000 to £30,000) to determine whether or not a treatment or service is cost-effective given a patient’s age and the state of health and quality of life the patient will have should the treatment or service be provided, and makes recommendations to the NHS regarding which services to cover and for whom.[ix] For example, the NHS restricts cervical screenings to patients between the ages of 25-64, with few exceptions.[x] Individuals who have not fully adhered to their doctor’s advice or taken their prescribed medication will be denied a heart transplant.[xi]

In Canada, which has a publicly-funded single payer health care system, the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health assesses the cost-effectiveness of drugs and medical technologies to make recommendations regarding the use of such treatments. The Patented Medicine Prices Review Board regulates the prices of new medicines as they enter the market and monitors prices over time with the authority to intervene if price increases are deemed to be “excessive”.[xii] Global budgets—which provide a fixed lump sum to a health care provider for all services furnished to all patients in a given time period (typically, a year)—were implemented as a tool to constrain growing health care expenditures. However, the use of this funding mechanism has limited the amount of services provided, resulting in long wait times and reduced access to care, and limits the incentive to increase efficiency in care provision.[xiii] The supply of physicians and nurses has also been restricted. Capped budgets and a limited supply of care providers has coincided with limited availability of medical resonance imaging (MRI) machines and the wait time for patients needing an MRI in Ontario was found to be seven months at one point[xiv]; there are nearly 3 times fewer MRI exams performed per 1,000 people in Canada than in the U.S., yet nearly 1.5 times as many scans performed per MRI machine in Canada, suggesting a significant lack of resources.[xv]

Conclusion

Given the scale of the budget shortfalls, and the share for which Medicare is responsible, IPAB is not likely to be able to substantially reduce Medicare spending within its statutory restrictions without significant adverse effects. Substantial, meaningful reforms are needed in Medicare, and successful reforms are most likely to come from expansion of and innovation within Medicare Advantage and Part D, rather than across-the-board cuts in payment rates. The competitive nature of these programs requires providers to improve care and reduce costs in order to gain customers (beneficiaries). An organization with such limited scope which almost necessitates it propose spending reductions to the very programs most likely to produce long-term savings will certainly have negative consequences for both health and budgets.

This post was originally published on December 3, 2015; it has since been updated to reflect more recent data and for accuracy.

[i] Section 3401: Revision of certain market basket updates and incorporation of productivity improvements.

[ii] http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/BILLS-111hr3590enr/pdf/BILLS-111hr3590enr.pdf

[iii] Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Robert Book, “Competition And The Medicare Part D Program,” Sept. 11, 2013, http://americanactionforum.org/research/competition-and-the-medicare-part-d-program

[iv] In years prior to 2018, the target growth rate is the projected 5-year average (ending with such year) of the simple average of the projected increase in the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) and the medical care expenditure category of the CPI-U. In determination years 2018 and beyond, the target growth rate is the projected 5-year average (ending with such year) of the percentage increase in the nominal gross domestic product per capita plus 1.0 percentage point.

[v] The 5-year average includes the two years prior to the determination year, the determination year, and the 2 years following the determination year, with the final year being the “implementation year”.

[vi] John C. Goodman, Gerald L. Musgrave, and Devon M. Herrick, Lives at Risk: Single-Payer National Health Insurance Around the World. 2004.

[vii] http://www.nhs.uk/news/2013/12december/pages/uk-cancer-survival-rates-below-european-average.aspx

[viii] http://www.bbc.com/news/health-28983924

[ix] https://www.nice.org.uk/proxy/?sourceurl=http://www.nice.org.uk/newsroom/features/measuringeffectivenessandcosteffectivenesstheqaly.jsp

[x] http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Cervical-screening-test/Pages/When-should-it-be-done.aspx

[xi] http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/heart-transplant/Pages/Introduction.aspx

[xii] http://www.commonwealthfund.org/~/media/files/publications/fund-report/2015/jan/1802_mossialos_intl_profiles_2014_v7.pdf

[xiii] https://www.cdhowe.org/pdf/Commentary_378.pdf