Insight

December 15, 2021

Improving DOE’s Loan Programs Office

Executive Summary

- The Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office offers loans for energy projects in an effort to commercialize novel technologies.

- The application process requires the completion of environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and adds significant delay to a project’s construction.

- By reducing the burden of NEPA review, projects could more easily attract private investors.

Introduction

The Department of Energy’s (DOE) Loan Programs Office (LPO) offers direct loans and loan guarantees for energy projects that rely on newly commercialized technologies or technologies applied in novel use cases that may be considered risky by private investors. This programming intends to aid in the commercialization of technologies that reduce greenhouse gas emissions but have yet to gain a foothold in the market.

Loan guarantees allow lenders to extend loans to fund energy projects with the guarantee that the Department of Energy will cover the cost if the borrower defaults, thus reducing lenders’ financial risk. Direct loans, on the other hand, simply remove the need to seek loans from traditional institutions.

As with most government funding, however, DOE’s LPO loans come with strings attached. Notably, its loan offers are contingent on the completion of an application process that may include environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). The duration of the environmental review alone may be two years. Reducing the review time and in turn, the regulatory risk, could increase the programming’s appeal to private finance partners.

DOE’s Loan Programming

The LPO administers three loan programs: the Title 17 Innovative Energy Loan Guarantee Program, the Advanced Technology Vehicles Manufacturing (ATVM) Loan Program—which provides direct loans rather than loan guarantees—and the Tribal Energy Loan Guarantee Program (TELGP). Companies must meet several criteria to qualify for one of these programs. The Title 17 program requires that projects be located in the United States and use a new or significantly improved technology to avoid, reduce, or sequester greenhouse gases and have a reasonable prospect of repayment. The ATVM loan program is open “to automotive or component manufacturers for reequipping, expanding, or establishing manufacturing facilities in the U.S. that produce fuel-efficient advanced technology vehicles or qualifying components,” or provide engineering integration. The TELGP is available for federally recognized Indian tribe or Alaska Native Corporation energy development.

As of December 31, 2020, the LPO has provided over $35 billion in loan guarantees and direct loans for more than 30 projects.[1] In fiscal year 2020, LPO disbursed over $29 million.[2]

Loan Process

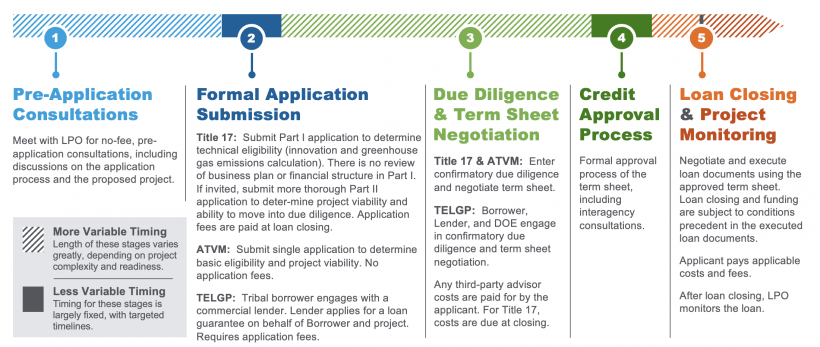

In order to secure debt financing, a potential borrower must complete the LPO’s review process. Based on the graphic below, most of the time in review is classified by the DOE “variable,” meaning that the length of these stages varies greatly with the “complexity and readiness” of the project. When an applicant has been invited into the due diligence phase, the LPO initiates environmental review under NEPA.[3] LPO’s documentation includes applicant environmental reviews were completed between 2010 and 2014, suggesting that for seven years no project has been invited to the due diligence phase of application review.

LPO Application Process Source: DOE

Source: DOE

NEPA review is required when the federal government undertakes decision-making that may impact the environment. In order to meet the statute’s requirements, LPO may be the lead agency, a cooperating agency, or adopt the NEPA review conducted by another agency as its own. If the project is to be constructed on land that belongs to the federal government, or alternatively, involves the construction of a type of infrastructure that is subject to federal approval, then an agency other than DOE may be conducting or has completed NEPA review before the LPO application process begins. According to the LPO, “[t]he average timeline for completing an environmental assessment is 6-9 months, and for an environmental impact statement around 18-24 months.”[4] Construction of a project cannot begin until NEPA review is complete.

Projects not sited on federal land are typically only subject to the environmental review deemed necessary by the state in which they are located. Were the project applicants not entering a financial commitment with the LPO, their projects would not be subject to federal jurisdiction. As a result, the choice to apply to the LPO can add a significant administrative commitment and delay project completion—and thus make it unappealing to private investors seeking expeditious returns on their investment.

To encourage novel technology companies and private investors to engage with the LPO, the regulatory risk associated with the programming needs to be eliminated. A simple solution would be to exclude projects seeking LPO loans from NEPA review should they be subject to another federal or state environmental review. The removal of the duplicative review process would eliminate the uncertainty created by government decision-making.

Conclusion

The DOE’s choice to finance a project is not an approval of a project or even necessarily an indication that it will be constructed. The LPO has no control over funds once they have been disbursed to the approved applicant. For this reason, in addition to the duplicative nature of the review, the applicants to LPO’s offering should be excluded from NEPA review. By removing this regulatory risk, projects that are seeking to eliminate the risk associated with the novelty of their technology would be able to accomplish what the program intended, securing private finance partners.

[1] https://www.energy.gov/lpo/portfolio

[2] https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/DOE-LPO_APSR_FY2020.pdf