Insight

November 8, 2022

How to Think About Horizontal Mergers: What’s Next for FTC & DOJ Guidelines

Executive Summary

- The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) must consider many factors when determining whether to challenge a proposed horizontal merger, a merger between direct competitors.

- Directing this review process are the “principal analytical techniques, practices, and the enforcement policy of the [DOJ] and [FTC] with respect to mergers and acquisitions involving actual or potential competitors” [1] outlined in the Horizontal Merger Guidelines (HMG) jointly published by the agencies.

- The most recent iteration of the HMG was adopted in 2010 and reflects decades of economic learning with respect to the competitive effects of mergers, a deeper understanding of markets, and refined agency practices, and this has resulted in the widespread adoption of the HMG by the courts.

- In response to President Biden’s executive order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy[2], the FTC and DOJ announced their intention to revise the HMG to “meet the challenges and realities of the modern economy;” [3] such changes could introduce novel theories of harm, adjustments to concentration thresholds, and other modifications to the HMG that threaten to abandon decades of economic advancements and limit the HMG’s persuasiveness in the courts.

Introduction

President Biden’s executive order (EO) on Promoting Competition in the American Economy ushered in a “whole-of-government” approach to antitrust policy. The order asserted that this new approach “[was] necessary to address overconcentration, monopolization, and unfair competition in the American economy.” In response, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) announced their intention to revise the Horizontal Merger Guidelines (HMG) to “meet the challenges and realities of the modern economy.”

The HMG outlines the “principal analytical techniques, practices, and the enforcement policy of the [DOJ] and [FTC] with respect to mergers and acquisitions involving actual or potential competitors.” The guidelines have seen numerous iterations. The first HMG was published in 1968 and was revised in 1982, 1984, 1992, 1997, and most recently in 2010. Each revision of the HMG reflected new economic learning and agency practices. Though the HMG does not have the power of law, it has been frequently cited in court decisions.

FTC Chair Lina Khan and DOJ Antitrust Division Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter take a more skeptical view of horizontal mergers, especially when a large firm is involved. Acting on this greater skepticism, the agencies could formulate additional theories of harm, adjust concentration thresholds, and make other modifications to the existing standards in the HMG that could broaden the scope of merger activity vulnerable to scrutiny. This analysis explains what the DOJ and FTC consider when challenging a merger, how the HMG has evolved, and why potential changes threaten to unravel decades of economic learning and the HMG’s adoption by the courts.

The Steps in the Merger Review Process

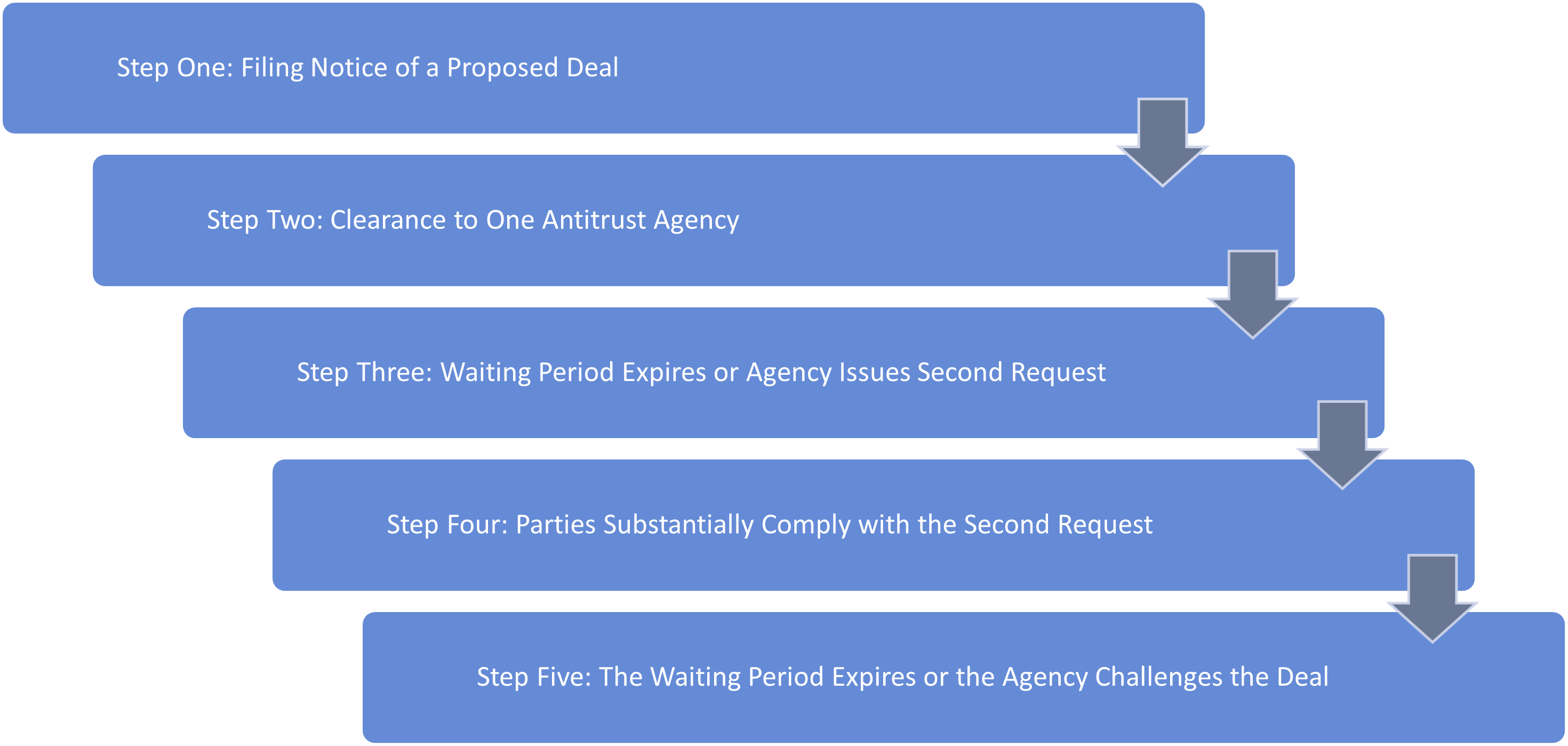

The Hart-Scott-Rodino Act[4] established the federal premerger notification program. Proposed mergers of a minimum value and parties of a minimum size must alert the FTC and DOJ with information about the merger.

Figure 1 lists the steps merging parties subject to this premerger notification program must follow before the merger is consummated. Details of each step can be found on the FTC Premerger Notification and the Merger Review Process website.

Figure 1

What Antitrust Enforcement Agencies Evaluate in a Horizontal Merger Review

Throughout the FTC or DOJ merger review process, the goal of the agency is to determine whether the effect of the merger “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly” (Clayton Act Section 7).

To make the case, the agency responsible for investigating the merger gathers evidence, including actual effects observed in consummated merges, direct comparisons based on experience, market shares and concentration in a relevant market, substantial head-to-head competition, and the disruptive role of a merger party. Such evidence comes directly from the merging parties, customers, or other industry participants and observers. [5]

To guide the information-gathering efforts, the agency often establishes a market definition to narrow the scope of the investigation. The market definition serves two purposes. First, it “specif[ies] the line of commerce and section of the country in which the competitive concern arises…. Second, market definition allows the Agencies to identify market participants and measure market shares and market concentration.”[6]

The first part of establishing the relevant market is to determine the product market. Here, the agency identifies overlapping product(s) sold by the two merging firms as well as the availability of substitutes. The availability of substitutes could lead to “multiple relevant product markets” being identified.[7] The 2010 HGM outlines a series of economic tests, including the hypothetical monopolist test, the agency will perform in its evaluation.

The American Action Forum (AAF) has published numerous pieces on specific antitrust cases including Illumina/Grail, Spirit/JetBlue, and Meta/Within discussing the importance of the relevant market and some of the tests outlined in the 2010 HMG.

Once the relevant market is determined and all available information is gathered, the agency is tasked with proving two theories of harm – unilateral effects and coordinated effects. Unilateral effects are those that “enhance market power simply by eliminating competition between the merging parties.”[8] A merger can also increase the probability of coordinated effects – those that “diminish competition by enabling or encouraging post-merger coordinated interaction among firms in the relevant market that harms customers.”[9]

The 2010 HGM also outlines various defenses merging parties can employ. Powerful buyers “may constrain the ability of the merging parties to raise prices.”[10] Additionally, new entrants into the market could thwart the potential harmful effects of the merger.[11] The agency estimates “whether entry will be timely[12], likely[13], and sufficient[14],” meaning that the new competitor must enter the market quickly enough to be profitable and strong enough to counteract any anticompetitive effect over a short period. The agency will also consider efficiencies generated by the merger. The HGM notes that “a primary benefit of mergers to the economy is their potential to generate significant efficiencies and thus enhance the merged firm’s ability and incentive to compete, which may result in lower prices, improved quality, enhanced service, or new products.”[15] Last, if one of the merging parties is likely to fail, the HGM asserts that “a merger is not likely to enhance market power if imminent failure…of one of the merging firms would cause the assets of that firm to exit the relevant market.”[16]

The guiding principle of all this information gathering, economic testing, and efficiency measuring is the consumer welfare standard. This standard, which has been the backbone of antitrust enforcement and litigation for more than 40 years, ensures that merger evaluations protect consumers from increased prices, reduced output, and lower levels of innovation.

The Building Blocks of the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines

The most recent version of the HMG, published in 2010, was built upon “earlier versions of the Guidelines, especially those released in 1982 and 1992, and on the 2006 Commentary on the Merger Guidelines,” according to Carl Shapiro, former DOJ Deputy Assistant Attorney General for Economic, Antitrust Division and joint DOJ/FTC Horizontal Merger Guidelines working group member.[17]

The first merger guideline was issued by the DOJ in 1968 and centered on the idea that “horizontal mergers that increase market concentration inherently are likely to lessen competition.” [18] The “focus on market concentration reflected unambiguous Supreme Court precedent” including Brown Shoe Co., Inc. v. United States where the court stated, “[t]he dominant theme pervading congressional consideration of the 1950 amendments [to § 7 of the Clayton Act] was fear of what was considered to be a rising tide of economic concentration in the American economy.”[19]

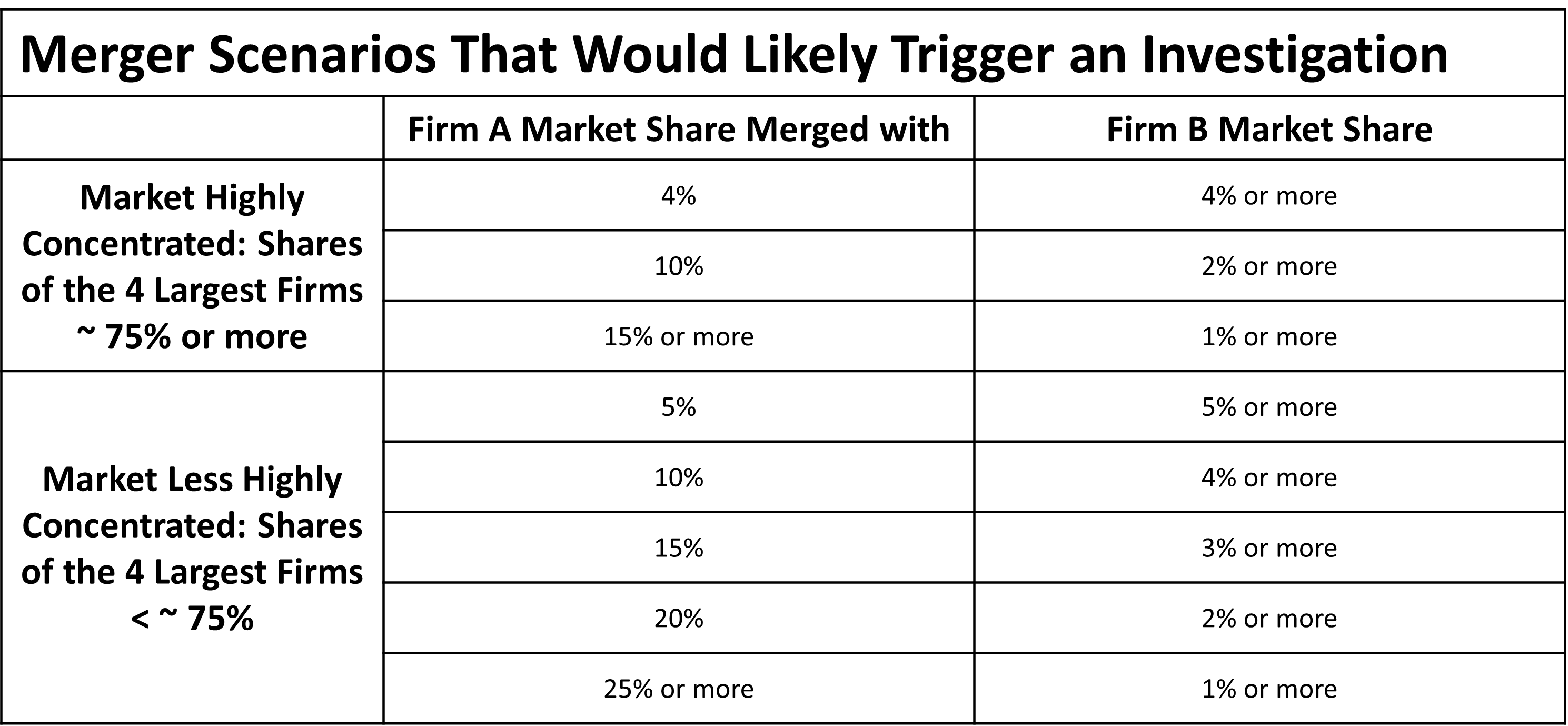

As a result, the 1968 merger guideline outlined various levels of market concentration that would likely result in a challenge by the DOJ.[20] Figure 2 shows these levels.

Figure 2

Created using information from the 1968 Merger Guidelines

For example, in a market where the top four firms controlled approximately 75 percent of the market (or greater), a merger between a firm with a 15 percent market share and a firm with 1 percent or more market share would be challenged. This set of rules was abandoned in subsequent guidelines as they proved too restrictive.

The next set of merger guidelines was published in 1982, and Shapiro dubbed them a “revolution” and highlighted “five innovations [that] formed the foundation on which all subsequent Merger Guidelines have been built.”[21]

These innovations included a “departure” from the emphasis on market structure that dominated the 1968 guidelines in favor of a “unifying theme…that mergers should not be permitted to create or enhance ‘market power’ or to facilitate its exercise.” The 1982 guidelines introduced the hypothetical monopolist test, a new measure of market concentration called the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), “expanded the discussion of competitive effects,” and “provided a list of factors that affect the ease and profitability of collusion” (coordinated effects).[22]

Shapiro explained that the “1982 Guidelines were written with relatively homogeneous, industrial products in mind…[and] reflected longstanding antitrust concerns for the performance of concentrated markets for basic industrial commodities.”[23]

This revolutionary change in the 1982 guidelines came soon after the publication of Robert Bork’s 1978 book “The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself,” which asserted that consumer welfare should be the crux of antitrust law and litigation.

The guidelines, according to Shapiro, were “slightly revised in 1984, but the next major change arrived with the 1992 Guidelines.”[24] The 1992 merger guidelines were the first jointly issued by the DOJ and FTC and “reflected the accumulation of Agency experience and the advance of economic learning during the 1980s.”[25]

This version of the merger guidelines introduced unilateral effects as well as a “more detailed and sophisticated analysis of entry” that included “the principle that entry must be ‘timely, likely, and sufficient.’”[26] Shapiro emphasizes that “[t]he introduction of unilateral effects…reflected and anticipated a shift in merger enforcement away from relatively homogeneous industrial commodities and towards more differentiated products…[and was] a major step in the evolution of antitrust enforcement from the industrial age to the information age.”[27]

The subsequent major revision took place in 1997. The most significant change was the “expansion…of the treatment of merger efficiencies.” This change “reflect[ed] an appreciation that mergers can promote competition by enabling efficiencies, and that such efficiencies can be great enough to reduce or reverse adverse competitive effects….”[28]

The evolution of the merger guidelines culminated with the most recent edition issued in 2010. This version “place[d] less weight on market shares and market concentration” and “follow[s] a more integrated and less mechanistic approach.”[29]

The 2010 HMG routinely reminds merging firms of this integrated approach. The Overview section of the HGM reads, “merger analysis does not consist of uniform application of a single methodology. Rather, it is a fact-specific process through which the Agencies, guided by their extensive experience, apply a range of analytical tools to the reasonably available and reliable evidence to evaluate competitive concerns in a limited period of time.”[30] In other words, the weight placed on a particular piece of evidence will vary based on the specifics of the case and market structure.

The underpinnings of the 2010 HMG rewrite were rooted in even more advanced economic analysis, improved agency practice, and a focus on the “consumer welfare standard” which, by that time, had been widely cited in court decisions. But the true test came after they were issued. Would these new innovations and practices be accepted by the courts? Shapiro and former FTC Bureau of Economics Director Howard Shelanski sought to measure the HMG’s success. The authors found that “In the 10 years since the FTC and DO[J] issued the 2010 HMGs… At a broad level, we find no instances in which the courts rejected any of the 2010 innovations. Nor do we find any instance in which any aspect of the 2010 HMGS – notably the reduced emphasis on market definition or the higher HHI thresholds – created an impediment for the DOJ or the FTC in bringing or proving a case in court…. Beyond that, numerous courts have either discussed or expressly accepted key elements of the 2010 revisions, with the clearest impact being the increased acceptance in courts of challenges based on unilateral effects.” They concluded that “All of this suggests that the 2010 HMGs will have further influence on the evolution of case law going forward.”[31] Simply put, the courts readily accepted the most recent revisions to the HMG.

Potential Changes to the New Horizontal Merger Guidelines

The impetus behind President Biden’s executive order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy was the assumption that the American economy has become more concentrated and was no longer a “fair, open, and competitive marketplace.”[32] In various sectors of the economy, the order alleged, consolidation was responsible for, among other things, increased costs for broadband, health care, and agricultural products, while stifling innovation in the technology sector. The order also asserted that “excessive market concentration threatens…the welfare of workers, farmers, small businesses, startups, and consumers.”[33] Past AAF research showed little change in the distribution of concentration across industries.

The order directed “the Attorney General and the Chair of the FTC…to review the horizontal and vertical merger guidelines and consider whether to revise those guidelines.”[34]

In response, the FTC and DOJ launched an “inquiry aimed at strengthening enforcement against illegal mergers.”[35] To address this, the agencies sought public input to help develop new merger guidelines. Some of the topics listed as areas of concern included: purpose and scope of merger review, presumptions that certain transactions are anticompetitive, use of market definition in analyzing competitive effects, threats to potential nascent competition, and unique characteristics of digital markets.[36]

Entirely addressing these areas and the concerns of the Biden Administration, the revised HMG will necessarily stray from its guiding principle of preventing consumer harm and adopt a more convoluted and broader scope encompassing harm to workers and competitors.

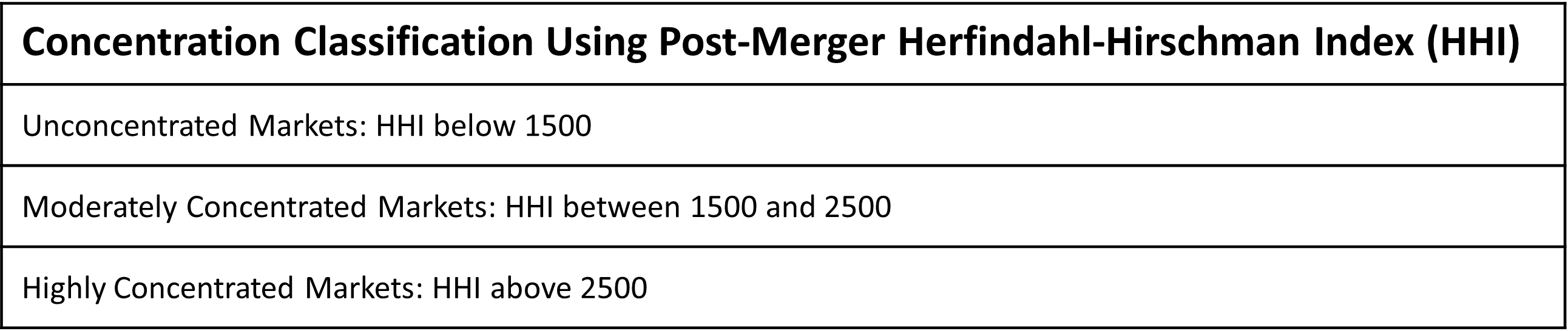

Given the language of the order and the FTC and DOJ’s focus on firm size, an obvious change will be changing the thresholds of industry concentration. A revised HMG will likely revert to earlier agency practices by putting greater emphasis on the HHI. Figure 3 shows the current HHI thresholds in the 2010 HGM.

Figure 3

Created using information in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines

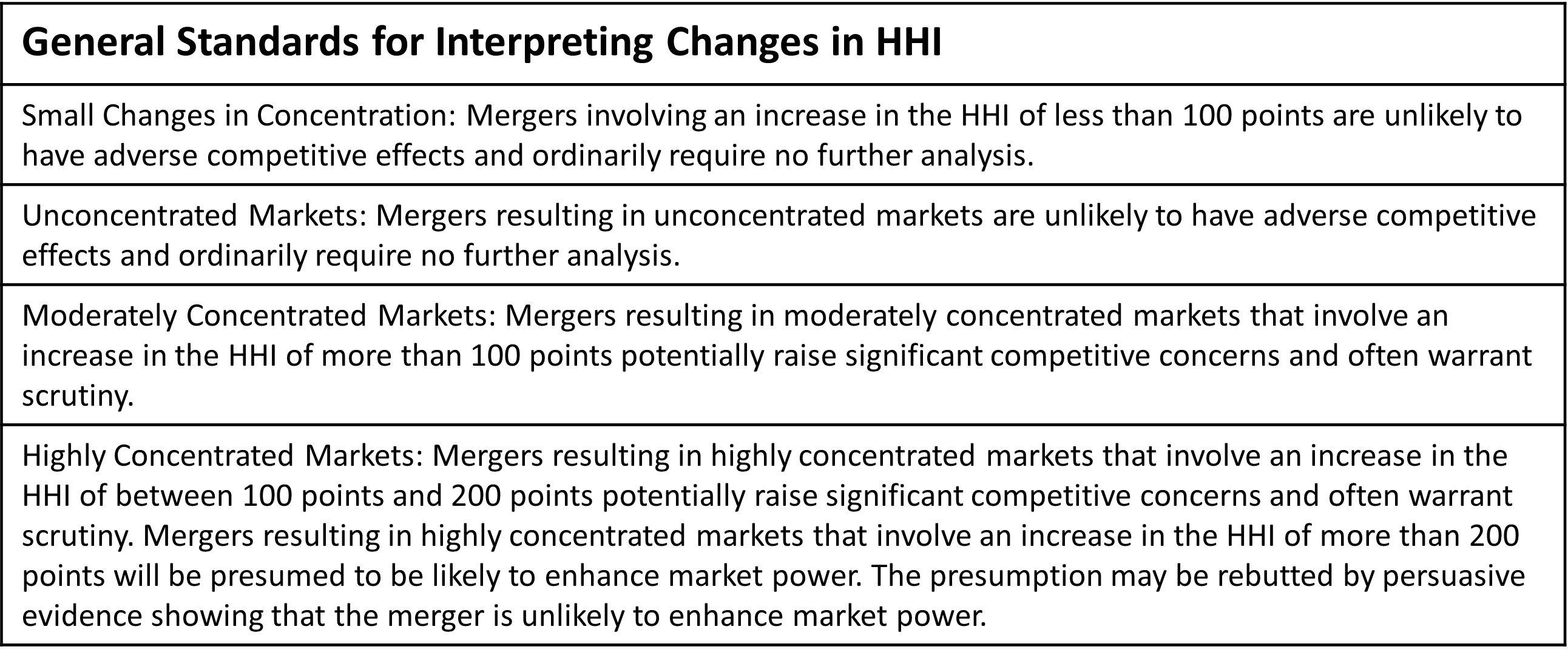

The agencies couple the concentration classification with a set of general standards in its assessment of the potential for competitive harm. The changes, and accompanying explanation, are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Created using information in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines

For more information and an example of the HHI analysis see Appendix.

It is reasonable to assume that changes to the HHI thresholds delineating various levels of concentration will be lowered. In other words, the current threshold signifying a highly concentrated market of 2500 or greater will be lower. Furthermore, the change in the HHI that presume anticompetitive effects will follow suit. Together, the probability that a merger is challenged increases.

Additionally, the FTC and DOJ will likely issue guidance on how they view the acquisition of nascent competitors. The agencies assert that established firms are eliminating a key source of innovation and competition through acquisitions. [37] AAF research found little evidence to support the claim that incumbent firm acquisitions are discouraging startups from forming.

Moreover, the DOJ and FTC, rather than issuing separate guidelines for horizontal and vertical mergers, will combine them into one. Kanter stated that “the guidelines have bifurcated horizontal and vertical analysis, yet often transactions don’t neatly fit into these categorizations.” He continued, “horizontal versus vertical analysis” narrows the agencies “to a two-dimensional view of modern markets that are often multi-dimensional.”[38] Vertical mergers, a merger between firms at different levels of the supply chain, are fundamentally different and require different analysis than a merger between competitors. Because of these intrinsic differences, the DOJ and FTC issued new Vertical Merger Guidelines in June 2020 (the FTC withdrew its support of the Vertical Merger Guidelines in September 2021)[39].

Such potential changes to the HMG threaten to replace the consistent, measurable, and objective application of antitrust jurisprudence guided by the consumer welfare standard with an inconsistent approach used to address other political goals including mitigating depressed employee wages, minimizing inequality, limiting harms to competitors, and preventing big firms from amassing political power.

Shapiro and Shelanski noted in their research that, “Because of the incremental nature of common law evolution through the adjudicative process, changes to antitrust case law come slowly and unevenly.”[40] This sentiment could serve as a warning to the FTC and DOJ that any meaningful departure from established practices by the agencies and economic analysis established in the 2010 HMG risks not being readily accepted by the courts.

Conclusion

The FTC and DOJ must consider myriad factors when determining whether to challenge a proposed horizontal merger. Directing this review process is the HMG.

The most recent iteration of the HMG reflects decades of economic learning with respect to the competitive effects of mergers, a deeper understanding of markets, and refined agency practices, all of which has led to the widespread adoption of the HMG by the courts.

In response to President Biden’s executive order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy,[41] the FTC and DOJ announced their intention to revise the HMG to “meet the challenges and realities of the modern economy.” [42] Such changes could introduce novel theories of harm, adjustments to concentration thresholds, and other modifications to the HMG that threaten to abandon decades of economic advancements and limit the HMG’s persuasiveness in the courts.

Appendix

The HHI is calculated by squaring the market share of each firm competing in the market and summing the results. For example, a market consisting of five firms with market shares of 30, 30, 15, 15, and 10 percent, the HHI is 2350 (302+302+152+152+102=2350). Prior to any proposed merger, this market is considered moderately concentrated. If a firm with 15 percent market share merged with another firm with 15 percent market share, that would leave the new market with four firms with market shares of 30 (total of the two combined firms), 30, 30, and 10 percent and an HHI of 2800 (302+302+302+102=2800). The change in the HHI is 450. Using the information in Figure 3 and Figure 4, the agency investigating the merger would conclude that the merger resulted in a highly concentrated market and, absent any other evidence, is presumed to be likely to enhance market power because the change in the HHI of 450 in this example is greater than 200 outlined in the HMG.

[1] https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010

[2] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/

[3] https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-jonathan-kanter-delivers-remarks-modernizing-merger-guidelines

[4] https://www.ftc.gov/legal-library/browse/statutes/hart-scott-rodino-antitrust-improvements-act-1976

[5] 2010 HMG § 2

[6] 2010 HMG § 4

[7] 2010 HMG § 4.1

[8] 2010 HMG § 1

[9] 2010 HMG § 7

[10] 2010 HMG § 8

[11] 2010 HMG § 9

[12] 2010 HMG § 9.1

[13] 2010 HMG § 9.2

[14] 2010 HMG § 9.3

[15] 2010 HMG § 10

[16] 2010 HMG § 11

[17] https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Shapiro-The-2010-Horizontal-Merger-Guidelines-From-Hedgehog-to-Fox-in-40-Years-2010.pdf

[18] Id.

[19] Id.

[20] https://www.justice.gov/archives/atr/1968-merger-guidelines

[21] https://www.law.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Shapiro-The-2010-Horizontal-Merger-Guidelines-From-Hedgehog-to-Fox-in-40-Years-2010.pdf

[22] Id.

[23] Id.

[24] Id.

[25] Id.

[26] Id.

[27] Id.

[28] Id.

[29] Id.

[30] 2010 HMG § 1

[31] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11151-020-09802-x

[32] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/

[33] Id.

[34] Id.

[35] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/01/federal-trade-commission-justice-department-seek-strengthen-enforcement-against-illegal-mergers

[36] Id.

[37] https://www.davispolk.com/insights/client-update/recent-merger-challenges-show-doj-and-ftc-focus-nascent-competition

[38] https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-jonathan-kanter-delivers-remarks-modernizing-merger-guidelines

[39] https://www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1290686/download

[40] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11151-020-09802-x

[41] https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/07/09/executive-order-on-promoting-competition-in-the-american-economy/

[42] https://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/assistant-attorney-general-jonathan-kanter-delivers-remarks-modernizing-merger-guidelines