Insight

April 3, 2023

Biden Regulatory Rollback Would Not Prevent Another SVB

Executive Summary

- The Biden Administration has proposed a rollback of 2018 midsized bank regulatory reform with a view to preventing the collapse of another Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

- The 2018 banking reform tailored the Dodd-Frank Act such that a bank’s regulatory requirements better matched its risk profile; the absence of these reforms would have done nothing to prevent SVB’s collapse.

- SVB failed due to the inflationary macroeconomic environment, egregious risk management practices, and lax supervision; any of these would prove a better target for the Biden Administration’s efforts than bank capital requirements.

Context

The March collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) has left regulators and policymakers grasping for a regulatory solution to a market problem. One might think that the federal government had done enough already in the form of guaranteeing all of SVB’s deposits and the creation of a Federal Reserve (Fed) lending program allowing banks to exchange poorly performing collateral at par value instead of market value.

Yet this is exactly what the Biden Administration has proposed. In a valiant effort to find a culprit in the least likely places, the Biden Administration has seized on midsize bank deregulatory efforts under the Trump Administration as a stalking horse and in a recent fact sheet has urged the federal banking regulators to reverse this bank tailoring reform.

What, then, were the Trump regulatory reform efforts, what does Biden want to undo, and crucially, would these regulations have had any impact on SVB or prevent another collapse of its kind? On the latter, the troubling answer is: not in the slightest. The Biden Administration’s proposals are no more than political theater – a pantomime that would increase the regulatory burden on banks, thus increasing costs for consumers and disincentivizing new entrants to the marketplace. Moreover, the response to SVB’s collapse simply continues the ill-advised trend of Congress and the administration seeking to tell the Fed how to do its job.

The 2018 Midsize Bank Deregulatory Efforts

In May 2018, Congress passed the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act (S.2155), a financial services deregulatory bill aimed at scaling back and addressing some of the most burdensome aspects of the Dodd-Frank Act. S. 2155 sought to reform the prudential regulatory landscape, including reform of banking capital requirements, and was primarily aimed at community and mid-tier banks. (For more on the “tiering” of banks and the capital standards that apply please see a primer here.)

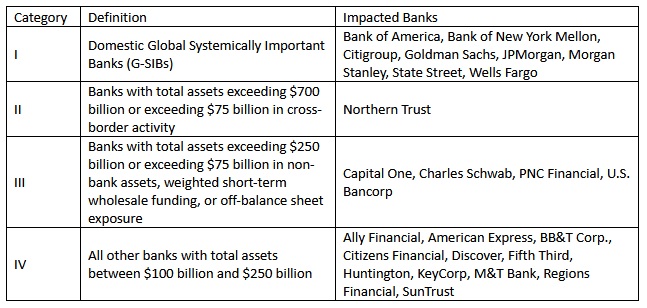

In particular, S.2155 raised the threshold for systemically important financial institutions from $50 billion to $250 billion while also empowering the Federal Reserve to articulate a new regulatory approach to supervising banks with assets exceeding $100 billion. The Fed fundamentally restructured the hierarchy by which it considers banks with assets exceeding $100 billion, creating four new categories, and outlined the regulatory relief that each category would see.

Under the Fed’s restructuring, banks from neither Category I nor II saw any regulatory relief or changes in capital or liquidity requirements. Category III banks received regulatory relief relating to bank capital requirements. Restrictions relating to the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) and the Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) were eased following the Fed’s proposal. Category III banks saw the LCR and NSFR requirements reduced to between 70–85 percent. Relief for banks in this category related only to bank capital requirements, but Category III banks became able to opt out of “accumulated other comprehensive income” (AOCI) reporting.

Category IV banks (the only banks to be considered “midsized”) saw the most sweeping regulatory relief. The LCR and NSFR requirements for these banks were removed entirely. The Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) stress testing requirements would still apply to these banks, but the annual stress testing requirement shifted to a biennial requirement, although banks would still need to provide an annual capital plan. Category IV banks were also able to opt out of not just AOCI reporting but also the countercyclical capital buffer.

At the hearing announcing the proposal, Fed Vice Chairman Randal Quarles asserted that “the character of regulation should match the character of a firm.” Enhanced tailoring in regulatory approach is a welcome indication that the Fed will seek to apply higher degrees of nuance, recognizing that not all banks are the same or face the same risk.

The Biden Fact Sheet

The Biden Administration’s fact sheet was clear in targeting those Category IV, or midsized, banks. Federal banking regulators have been instructed to reinstate the following regulatory requirements for midsized banks:

- the LCR and “enhanced liquidity stress testing”;

- annual supervisory capital stress tests;

- living wills (also known as recovery and resilience plans); and

- “strong capital requirements.”

In addition, the fact sheet proposes that regulators consider:

- reducing the regulatory transition periods for banks moving between categories;

- strengthening bank supervision;

- expanding long-term debt requirements; and

- ensuring that the costs of replenishing the Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) are not borne by community banks.

Analysis

Could undoing the 2018 bank tailoring reform have prevented SVB’s collapse? It is extremely unlikely.

SVB customers withdrew $42 billion (almost a quarter of all total assets) in a single day of trading at a rate of over $1 million a second. By comparison, the previous largest bank run in modern U.S. history took place in 2008 at Washington Mutual bank, which lost “only” $16.7 billion over 10 days. Fundamentally, no bank is capable of withstanding a shock of this magnitude, particularly over such a short time. Any system of bank capital requirements or opt-in ratios that could prevent this would be so hobbling that it would render the banking industry incapable of actually issuing loans at all; to pretend that bank capital requirements writ large could have prevented SVB is hubris.

More specifically, Daniel Tarullo, the Fed’s head of regulation under President Obama, noted that undoing the midsize bank tailoring in 2018 would not have prevented the collapse of SVB. Stress testing is simply not performed at these orders of magnitude. Living wills are designed to only come into effect after the crisis (and there is little evidence that SVB’s unwinding was particularly disorganized, the one potential exception being the FDIC’s curious delay at attempting to find a buyer for the bank). The LCR would not have prevented SVB from taking on excessive interest rate risk. The 2018 bank tailoring reform is essentially neutral on SVB’s circumstances.

The fact sheet is not entirely without merit, however. At several points the Biden Administration points to supervisory failings, one of the least visible aspects of SVB’s collapse. SVB presented a number of extremely clear warning signs, both specific to the bank (an over-dependance on a limited client sector and a ludicrously small number of loans guaranteed by the FDIC) and so basic as to be considered textbook (the sudden expansion in assets under management that catapulted SVB into the midsized tier in the first place and its egregious risk management). A review of the bank’s supervision in the run up to the crisis will be key to understanding SVB’s collapse; it is a shame, then, that the review will be lead by the SVB’s own supervisor. Reducing regulatory transition periods and long-term debt requirements are sensible topics to review given how central they were to SVB’s fall, but neither were a feature of the 2018 banking regulatory relief.

If reversing the 2018 banking reform would not have prevented the SVB collapse, nor another banking collapse, what would this rollback achieve? Undoing the tailoring efforts of the Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act would actually decrease the discretion of the Fed to tailor regulation to the specific needs of a particular firm. While bank capital requirements would largely stay the same, the regulatory burden of compliance would significantly increase, and these costs would necessarily pass to consumers. This regulatory rollback also sends worrying signs the administration and Congress are prepared to continue interfering with the Fed’s independent dual mandate, at a time when the Fed grows ever more in its role as not simply regulator and supervisor of the economy but also participant. The Term Bank Lending Facility erased at a stroke over half of the painstaking progress the Fed has taken to reduce the size of its balance sheet in its continued efforts to combat inflation.

Conclusions

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed because of the difficulties of an inflationary macro-economic environment, egregious risk management, and light-touch supervision. These are not problems readily solved by Congress, the financial regulatory agencies, or the Biden Administration. That there is even a “problem” to solve is a debate that we seem to have skipped entirely. Why should a poorly managed bank be saved, when the weakest performers in every other industry are allowed to fail? The 2018 deregulatory efforts would not have prevented the collapse of SVB and reinstating them will not prevent another bank run. The Biden Administration should not assume that just because it can, it should; if you are wielding a hammer, don’t assume everything is a nail.