Testimony

March 9, 2023

Testimony on Inflation: A Preventable Crisis

United States House of Representatives Committee on Oversight and Accountability Subcommittee on Health Care and Financial Services

* The views expressed here are my own and not those of the American Action Forum.

Chairwoman McClain, Ranking Member Porter, and members of the subcommittee, thank you for the privilege of appearing today to discuss inflation and the economic outlook. I hope to make the following main points:

- Due to prior policy errors, the United States is facing inflation levels previously unseen in a generation.

- Overall budget policy should not further exacerbate inflation through excessive spending.

Let me discuss these in turn.

The Macroeconomic Environment

In some respects, the current state of the U.S. economy is quite solid. Real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) rose 0.9 percent from the 4th quarter of 2021 to the same quarter in 2022, although in doing so it accelerated to an annual rate of 2.7 percent in that quarter. The unemployment rate stood at 3.4 percent in the January employment report. Wages are rising; average hourly earnings are up 4.4 percent from January 2022 – 5.1 percent for non-supervisory and production workers.

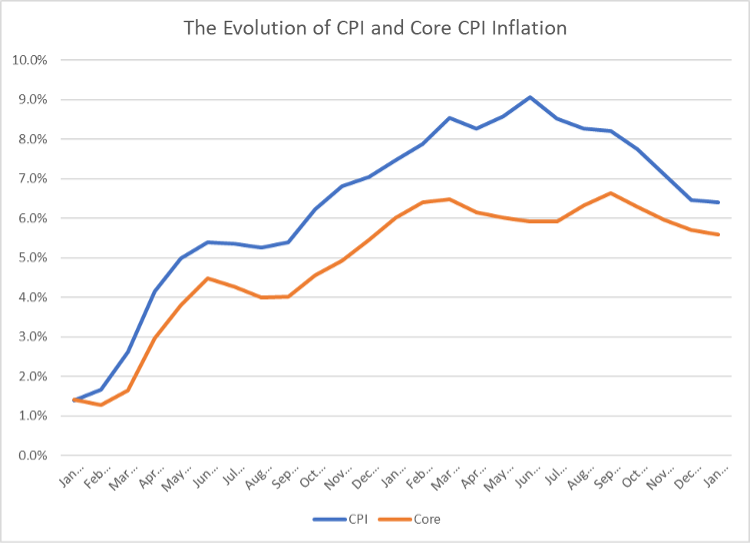

The Achilles heel of the outlook, however, is the worst inflation problem in 40 years. As measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), year-over-year inflation has risen from 1.4 percent in January 2021 to 6.5 percent in January 2022, after peaking at 9.1 percent. (See chart, below.) So-called “core” (non-food, non-energy) CPI is up from 1.4 to 5.6 percent over the same period. In each case, the measures have experienced their highest levels since 1982 and exceed the pace of wage increases.

Yet even these data disguise the pain of inflation. Over one-half of the typical family budget is devoted to food, energy, and shelter (FES) and the composite inflation for these items is currently 8.5 percent. The shelter component of the CPI (one-third of families’ budgets) is a particular burden on families. Shelter inflation is currently 7.9 percent year over year, up from 7.5 percent in December and having risen every month for the past two years.

Inflation is simply a tax on families’ standard of living. In 2021, the median household income was $70,784. An inflation rate of 6.5 percent imposes a $4,600 tax on that income. Similarly, the inflation in FES is tantamount to taking $3,000 from the budget for core household spending. Finally, the “shelter tax” from inflation is $1,845 at current inflation rates.

Clearly, inflation is imposing economic distress on all Americans. These data raise the important question: How did the United States develop this inflation problem?

Policy Responses to the COVID-19 Recession in 2020

The sharp downturn in the spring of 2020 was different in character, deeper, and more rapid than any postwar recession. In response, on a bipartisan basis, Congress and the administration responded in a timely fashion, with programs of necessarily large scale and by-and-large appropriate design.

During the 2nd quarter of 2020, GDP fell by nearly 10 percent, rivaling the decline of 12 percent during the entire year 1932 – the worst year of the Great Depression. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act was passed in March 2020 in bipartisan fashion and was a response of roughly 10 percent of GDP. CARES was timely and appropriate in its scale. The specific programs were also for the most part well-designed. In the aftermath of CARES, employment growth resumed in May 2020 and GDP recovered by roughly 8 percent in the 3rd quarter.

In the late fall and early winter of 2020, however, a new wave of COVID-19 infections arose across the country and headwinds to growth re-emerged. Congress and the administration again responded in a timely, bipartisan fashion with the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021, which included roughly $900 billion in economic support modeled on the design of the CARES Act. The economy weathered the COVID-19 stress and grew at a strong 6.5 percent in the first quarter of 2021.

Policy Actions in 2021 and the Emergence of Inflation

In contrast to the policy actions in 2020, the major action in 2021 – the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) – was partisan in nature, untimely, excessively large, and poorly designed. It is simply a major policy error.

As the economy entered 2021, it grew strongly due to the continued support and the arrival of the vaccines as an additional weapon in the fight against the coronavirus. The $1.9 trillion ARPA was advertised as much-needed stimulus to improve the state of the economy and restore growth. The economy was no longer in recession, however, and was growing at a roughly 6.5 percent annual rate. There was simply no need for additional stimulus, especially as a large fraction of the household support in the CARES and Consolidated Appropriations Acts had been saved and was available.

Worse, the ARPA was excessively large. Real GDP at the time was below its potential, with the output gap somewhere in the vicinity of $450 billion (in 2012 dollars). The $1.9 trillion stimulus was a bit over $1.6 trillion in 2012 dollars. Thus, the law was a stimulus of over three times the size of the output gap that needed to be closed to get the economy back to potential. Based on any reasonable economic theory of stimulus, $1.9 trillion is far too large, particularly given supply constraints. The ARPA (passed in March) did not appreciably alter the pace of growth from the first to the second quarter, but it did fuel inflation.

The 6.5 percentage point jump in CPI inflation has been rivaled only twice in the postwar period – during 1951 when it jumped as much as 10.6 percentage points and 1974 when the rise hit 6.1 percentage points. Both episodes are instructive. The 1951 episode is a cautionary tale about over-stimulating the economy. In this case, year-over-year growth in gross domestic product (GDP) entered the year in double-digit territory and prosecution of the Korean War layered on year-over-year growth government spending that peaked at 49 percent in the third quarter. Excessive government spending in a hot economy can quickly fuel inflation.

In contrast, the 1974 episode featured the exact opposite of demand stimulus. Instead, it reflects a huge supply cost shock – the quadrupling of oil prices due to the OPEC oil embargo. Cost increases can quickly be passed along to consumers, even if the economy is moving toward recession.

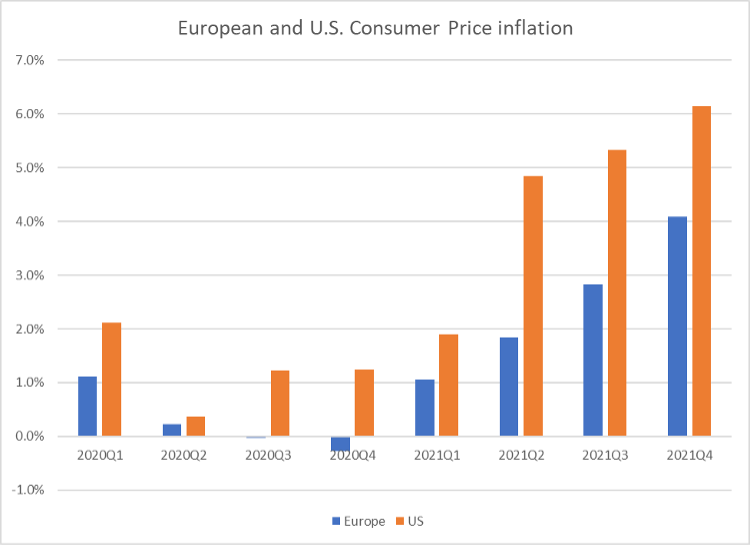

The inflation of 2021 reflects a combination of these forces. The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on labor markets worldwide, and the resulting disruptions in supply chains and goods production have been well-documented. These supply constraints increased costs and generated higher inflation across the globe. European consumer price inflation, for example, increased about 1 percentage point each quarter and ended 2021 at 4 percent. (See chart, below.) Part of the U.S. experience is driven by supply chain issues, as well.

But the ARPA added fuel to the fire. Inflation responded immediately to the policy error, jumping from 1.9 percent in the 1st Quarter to 4.8 percent in the 2nd Quarter – nearly three times the increase in supply-driven inflation in Europe. The fiscal stimulus was reinforced by an aggressively accommodative monetary policy that featured zero percent interest rates and continuous, large monetary infusions. Inflation continued to rise as the year went on.

Continued Policy Actions and Inflation

In the period after the ARPA, Congress passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, known as the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework (BIF). Did this exacerbate the inflation problem? First, despite all the claims of passing a trillion-dollar infrastructure bill, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) indicates that discretionary spending will rise by $415.4 billion over the next 10 years. This is significant but not a fiscal earthquake like the ARPA.

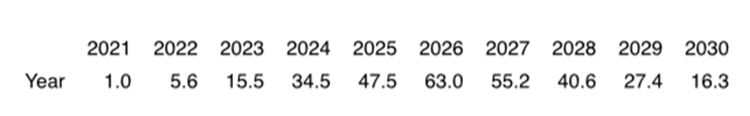

Second, the BIF will not generate any significant near-term stimulus or inflationary pressure. The table below shows a rough translation of the CBO score into calendar-year spending impacts, including the mandatory spending offsets. In a roughly $21-trillion economy, another $5.6 billion in spending (0.026 percent) simply is not going to move the macroeconomic needle. Even at the maximum, the impact will be below one-half of 1 percent of GDP.

Third, while the bill will not create additional inflation pressure, it will also not solve the administration’s current inflation-related political problems. There just is not enough impact in the near term to accomplish this task. Even at the peak, this would require a more significant impact on productivity and aggregate supply, and these dollars are not large enough to accomplish this kind of supply expansion.

Nevertheless, other pieces of legislation did contribute to the durability of the inflation problem. The first to think about is the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). To be clear, the IRA will not reduce inflation. In fact, no single piece of legislation will do that. What matters, instead, is the overall tax-and-spend (fiscal) policy of Congress. Indeed, as Gordon Gray nicely documents, the two big items Congress passed are the CHIPS Act and the IRA. Combined, they would raise taxes by about $830 billion and increase spending by $515 billion, yielding $315 billion in deficit reduction. That sounds anti-inflationary. Unfortunately, a closer look reveals the bills would not begin to materially reduce the deficit until 2028 – that is, five years from now. It will be up to the Federal Reserve to bring inflation under control.

Progress in Fighting Inflation

The Federal Reserve Board has taken the lead in measures to reduce inflation to its target rate of 2 percent. It has raised its policy rate – the federal funds rate – to an upper bound of 4.75 percent since March 2022 and simultaneously engaged in “quantitative tightening” by allowing its portfolio of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to shrink. By recent standards, these rates are relatively high and have happened relatively quickly. This policy has produced some calls for the Fed to stop, or even reverse, its tightening of monetary policy.

The January price index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE) data laid to rest any notion that the Federal Reserve Board had moved too fast, or even already had overdone, in tightening financial conditions to fight inflation. The top-line inflation measure jumped to a 7.7 percent annual rate, up from 2.4 percent in December. This caused the year-over-year rate of inflation from January 2022 to come in at 5.4 percent, a tick up from 5.3 percent the month before. So, clearly inflation is far from its 2 percent target and is not dropping rapidly. But some of the details are even more interesting.

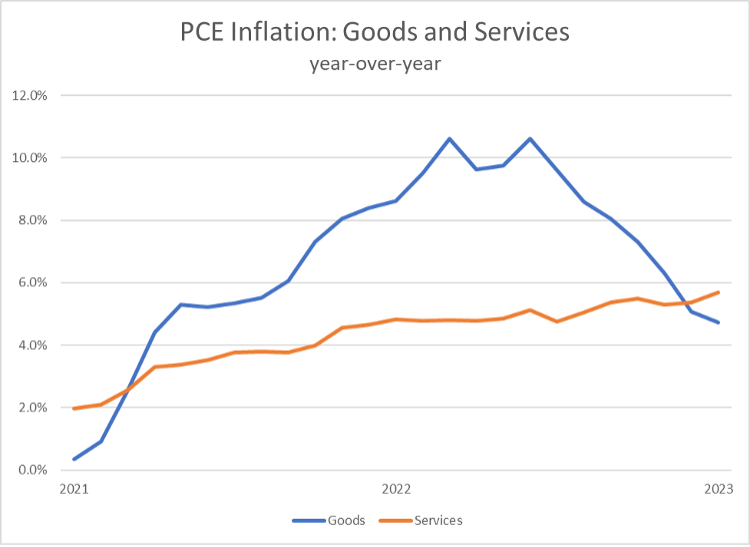

As shown in the graph below, there has been real progress in the battle against goods-price inflation. After peaking at 10.6 percent early in 2022, it has fallen to 4.7 percent and appears to be on a steady downward trajectory. Doubtless the Fed’s efforts have been aided by the ebbing of pandemic interference in supply chains, which are much more significant in goods than services. Indeed, the rise in the Fed’s policy rate since early 2022 has put no dent in service inflation. It has risen steadily beginning in early 2021 to reach 5.7 percent in the most recent data.

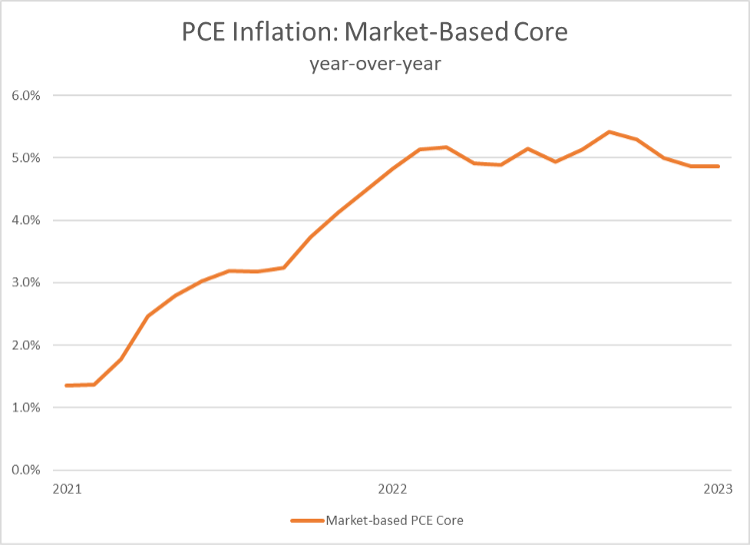

There is a second perspective on the Fed’s lack of progress. In the next graph, the focus is on the core (non-food, non-energy) PCE price index based only on observed market transactions (as opposed to imputing some of the unobserved prices). This series shows the rise during 2021 to 5.2 percent in early 2022. Since then, market-based core inflation has simply remained stubbornly elevated.

The upshot is to reinforce the simple facts that the Fed is far from done raising rates, inflation will not return to its 2 percent target quickly, and that a sustained regime of rate increases elevates the risk of a recession.

Thank you and I look forward to your questions.