Research

January 23, 2018

Student Loan Counseling: Does the Federal Mandate Give Borrowers Necessary Financial Skills?

Executive Summary

- Since 1986, the federal government has mandated that federal student loan borrowers receive some form of financial counseling, yet over a quarter of borrowers are in some form of non-payment and at risk of defaulting.

- Despite research showing that financial education can improve individuals’ financial status, a decreasing number of states are providing general economic courses. Other research indicates that the prevailing models for educating students about their school loans are failing.

- Federal and state policymakers, in conjunction with leaders from secondary and postsecondary institutions, should reform the policies governing student-loan education, including by giving greater flexibility to colleges and universities to provide targeted counseling to at-risk students.

Introduction

Making an informed decision regarding the financing of a college or professional degree or credential is difficult for many would-be students. Most are initially shocked by the sticker price of higher education but, with access to easy credit, forge ahead nevertheless with little more than faith that managing student-loan debt is easily accomplished. After all, if Uncle Sam didn’t want us to have these loans, then why would he make them so easy to get?

The amount of student debt in the United States is large, and growing. The Department of Education (ED) suggests that 41 percent of college undergraduates receive a federal student loan to pay for college, and [1] approximately 44 million of these borrowers have amassed more than $1.3 trillion in total outstanding student loan debt.[2] Students are also borrowing increasingly large sums: Between 1996 and 2006, the amount of federal loans per full-time enrolled undergraduate student increased 47 percent, from $3,210 to $4,720.[3] The annual total that the federal government dispersed in federal loans for undergraduate students increased from $28 million to more than $60 million during the same decade.[4] Moreover, reports suggest that 19 percent of students who graduated from public and private nonprofit colleges or universities held private loans.[5]

This debt can be very risky for both the government and students: while the federal 3-year cohort default rate has decreased in recent years, there are still slightly more than 12 million borrowers, representing $321 billion in outstanding federal direct loans, that are in some form of non-payment and at risk of defaulting. And today more than 8 million borrowers are nine months or more behind making even a $1 payment toward their student loan debt.

To reduce the likelihood of significant financial stress after their postsecondary education is complete, students need to clearly understand their credit lending options before their postsecondary education begins – and before they assume this debt. For most student borrowers, however, the only credit management or financial education they receive is the financial aid counseling mandated by federal statute – and even this is only provided after they have agreed to a federal loan.

This required counseling service aims to improve college students’ financial literacy, provide the necessary financial management skills, and help students understand loan repayment options. It is also intended to increase college enrollment and completion rates, while reducing loan default rates. Nevertheless, the statistics above show that this counseling is not working. The time is ripe for significant reform of student loan counseling.

Federal Financial Aid Counseling

Whether through statutory language or regulatory requirements, the federal government has mandated that federal student loan borrowers receive some form of counseling since the 1986 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. Table 1 below highlights the changes to loan counseling requirements and the years they were made.

Table 1. Changes to Federally Mandated Student Loan Counseling.

| Year | Event |

| 1986 | The Higher Education Act amendments of 1986 added an exit counseling mandate, requiring that each eligible institution shall, through financial aid officers or otherwise, make available exit counseling for borrowers of loans. This was the first statutory mandate for exit counseling. |

| 1989 | The Department of Education issued comprehensive default reduction regulations, requiring schools to provide students with additional loan counseling and to take specific steps to reduce loan defaults. |

| 1998 | Amendments to the Higher Education Act clarified that using electronic means to provide personalized exit counseling is not prohibited. |

| 2008 | The Higher Education Opportunity Act of 2008

· Added entrance counseling requirements for all colleges, · Encouraged the use of interactive programs for testing the borrower’s understanding of the terms and conditions of the borrower’s loans, and · Clarified that lenders could provide counseling for schools. |

These mandatory counseling sessions are intended to provide basic information about federal loans, such as loan terms and conditions, rights and responsibilities of the borrower, the use of the Master Promissory Note (MPN)[6], repayment obligation, the availability of the National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS)[7], and the likely consequences of default. The counseling can be delivered in several forms, including an in-person presentation, an online program, or an audiovisual presentation. Entrance counseling must be provided prior to the time the first disbursement of a loan is delivered, and exit counseling must be conducted shortly before a student leaves school or reduces enrollment to a half-time basis.

In practice, the most effective financial assistance counseling would be personalized, in person, and prior to a student accepting a loan, one study indicates.[8] Due to a lack of resources, however, many schools use the Department Education’s (ED) online loan counseling tool to comply with regulations. The National Association of Student Financial Aid Administrators’ 2015 Administrative Burden Survey found that financial aid offices often do not have enough staff to provide in-person counseling. Additionally, operating budgets for financial aid offices have remained constant or even decreased. This lack of investment is surprising given the risks schools face for high default rates: ED has regulated that institutions of higher education with high default rates (40 percent or higher one-year cohort default rates, or 30 percent or higher three-year cohort default rates) lose access to federal student aid programs – a primary source of funding for nearly all postsecondary institutions.

Unfortunately, the content provided through the counseling requirement has proven to be minimally informative. In 2012, researchers at Iowa State University interviewed participants to explore student effects of loan counseling in the financial aid processes.[9] The study found that no survey participant remembered the financial information presented in the loan counseling. Moreover, no student or parent expressed concern about repayment or default after participating in the exit counseling.

With an alarming number of borrowers heading down the road to default, and as federal policymakers work to reauthorize the Higher Education Act, a comprehensive review of the effectiveness of financial aid counseling is in order.

The Need for Research

While some studies have evaluated high school seniors’ financial knowledge and management skills, little literature evaluates how an incoming college freshmen’s financial literacy affects his or her decisions for how to finance college. And while most researchers assume that improved financial education is needed, there is no conclusive evidence identifying which qualities of financial education programs make them most effective for student borrowers. There is also no conclusive research that identifies which delivery method or curriculum most effectively provides financial knowledge.

Further, there is little research examining whether financial aid offices have access to sufficient resources to provide meaningful financial aid counseling services. Research has largely ignored the impact of entrance counseling on loan borrowing amounts, as well as the relationship between exit counseling and cohort default rates. The existing research examining the effects of financial aid counseling, conducted by ED, has proven less than definitive.[10] And while some research finds that respondents who have received financial education typically perform better on financial literacy tests, additional research is needed to prove a causal relationship between financial literacy and loan repayment.

Teaching Financial Management Knowledge and Skills

U.S. high schools are failing to ensure that college-bound-freshmen have the financial knowledge and management skills to make their first major financial decisions. While federal loans are a cost-effective and dependable resource for students financing a higher education, understanding debt management is vital to increasing the likelihood that an investment in education pays off.

Financial Education

One method of delivering financial knowledge and skills to high school seniors is through financial education coursework. Unfortunately, survey results have shown that high school seniors lack access to such courses.

The Council for Economic Education (CEE) collected K-12 economic and financial education data from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The 2016 survey found that only 22 states required that high schools offer a course in personal finance, and only 17 of those states require high school students take a course in personal finance. Moreover, only 20 states – two fewer than in 2014 – require high school students take a course in economics.

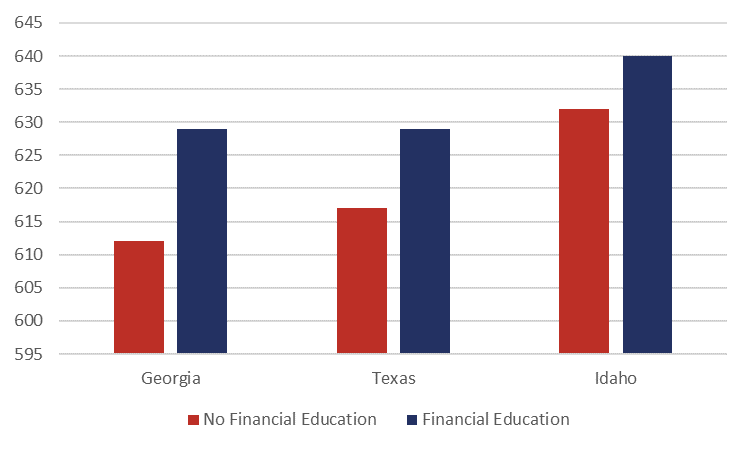

Despite the limited reach of financial education, there is some evidence that financial education has positive effects. The Federal Reserve Board conducted a study on the effects of state mandated financial education in 2014. Using a host of credit report data, the authors examined young adults in three states where personal financial education mandates were implemented. They compared the credit scores and delinquency rates of young adults in each of these states pre- and post-implementation. Young people who were in school after the implementation of a financial education requirement had higher relative credit scores and lower relative delinquency rates than those in control states, the study found.

Chart 1. Effects of Financial Education on Personal Credit Scores

Source: The Federal Reserve Board[11]

The study provides an important snapshot of the credit worthiness of young adults after completing coursework in financial education, and the results support greater inclusion of these courses in secondary school curriculum. The study did not, however, look specifically at the financial behaviors or repayment rates of student loan borrowers who have taken these courses.

Financial Literacy

Financial education provides an understanding of how to manage personal finances, whereas financial literacy is the ability to use and apply financial knowledge. For insight on U.S. students’ financial literacy, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which conducts educational surveys of 15- and 16-year-old students, provides the best insight.

The survey primarily evaluates students’ performance in math, reading, and science, but it also assesses financial literacy. Eighteen countries and economies participated in the PISA 2012 financial literacy assessment. The results ranged from an average score of 603 points for students in Shanghai, China to an average of 379 points for Colombian students. The mean score for U.S. students was 492, which ranked ninth out of 18 participating countries and economies. About 17.8% of U.S. students scored in the bottom level of financial literacy, compared to 15.3% in other OECD countries. Only 9.4% of U.S. students scored in the top level of financial literacy (Level 5), compared to 9.7% across OECD countries.[12]

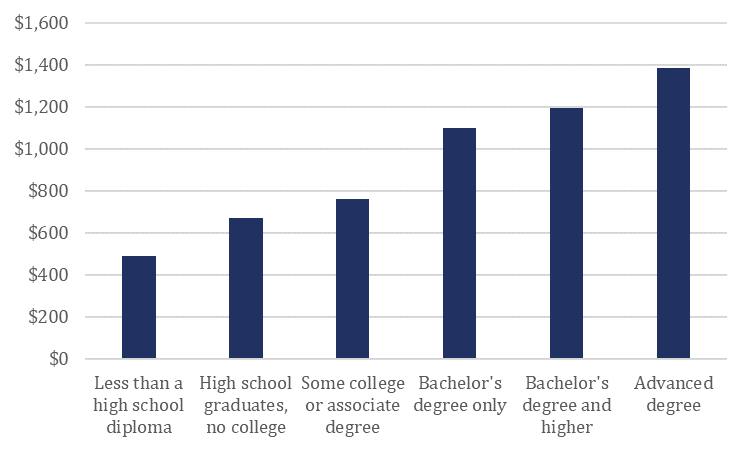

There is tremendous value in higher education, as shown by Chart 2, below. However, far too many students are taking on debt while also failing to obtain a degree or credential. This is proving to be a recipe for financial ruin: earnings often fail to provide enough for repayment, and federal loans cannot be discharged. In time, what began as a modest loan quickly turns into crippling debt due to fees and interest.

Chart 2. Median weekly earnings by educational attainment in 2014

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics[13]

Policymakers mandated the offering of loan counseling to mitigate this potential debt dilemma. Regrettably, it is increasingly clear that the current system of loan counseling is not achieving the intended outcome.

Policy Recommendations

Financial literacy among high school students should be improved.

State policymakers must prioritize increasing student financial literacy rates to ensure potential postsecondary students have adequate knowledge and skills to make their first major financial decision. States can require that schools offer additional courses in personal finance and perhaps even require that students complete them. Moreover, additional resources could be allocated to high school counseling programs designed to inform students of postsecondary opportunities. This extra funding could allow, for example, counselors to provide assistance beyond simply selecting an appropriate school and program of study.

Loan counseling should begin earlier and be supported with better data.

Initial loan counseling should be provided earlier in the process for those seeking federal financial aid, ideally as a part of completing the Free Application for Federal Student Aid. Additionally, the Office of Federal Student Aid should provide hypothetical examples of loans to demonstrate how the cost of various institutions (i.e. 2-year, 4-year, public, private, for-profit, in-state or out-of-state) affects expected monthly payments, should loans be necessary. The Office could also provide employment rates and average salaries for graduates of different programs of study to prospective students, so that borrowers have a sense for their ability to repay their student debt.

Institutions should be allowed to design and implement financial aid counseling services.

Federal guidelines prohibit higher education institutions from requiring more than the mandated entrance and exit loan counseling services, out of a fear that increasing burdens would discourage some from participating in the direct loan program. However, given that the schools’ access to federal aid programs is contingent on cohort default rates, some institutions have expressed interest in providing more stringent, long-term financial counseling services. These services would go beyond basic loan counseling by taking into account academic progress and other predictive indicators to ensure student borrowers remain on track to graduate and are not over-borrowing to finance their education. These counseling programs could be required throughout the term of enrollment. Other institutions have proposed offering voluntary financial counseling after students have graduated.

Conclusion

A postsecondary education should be a positive experience that paves a path to a stable career and the pursuit of the American dream. Unfortunately, millions of student loan borrowers are dropping out short of graduation and finding that the loans quickly become an overwhelming burden. Strategic reforms would ensure that students have the financial knowledge necessary to make informed decisions about debt, and would allow post-secondary institutions to design unique counseling services that target at-risk borrowers. With smart reform, the goal of fewer people defaulting on their student loan debt can be realized.

[1] U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, 2011-12 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (NPSAS:12). (This table was prepared January 2014.)

[2] Zack Friedman. Student Loan Debt In 2017: A $1.3 Trillion Crisis. Forbes. FEB 21, 2017 www.forbes.com/sites/zackfriedman/2017/02/21/student-loan-debt-statistics-2017/#734f9f30661d

[3] Trends in Student Aid. 2015 The College Board. FIGURE 1 Average Aid per Full-Time Equivalent (FTE) Student in 2015 Dollars, 1995-96 to 2015-16

[4] Trends in Student Aid. 2015 The College Board. TABLE 1A Total Undergraduate Student Aid in 2014 Dollars (in Millions), 1994-95 to 2014-15, Selected Years

[5] Debbie Cochrane and Diane Cheng. Student Debt and the Class of 2015. The Institute for College Access & Success http://ticas.org/sites/default/files/pub_files/classof2015.pdf

[6] The Subsidized/Unsubsidized Master Promissory Note (MPN) is a legal document in which you promise to repay your federal student loan(s) and any accrued interest and fees to your lender or loan holder. There is one MPN for Direct Subsidized/Unsubsidized Loans and a different MPN for Direct PLUS Loans. Most schools are authorized to make multiple federal student loans under one MPN for up to 10 years.

[7] The National Student Loan Data System (NSLDS) is the U.S. Department of Education’s (ED’s) central database for student aid. NSLDS receives data from schools, guaranty agencies, the Direct Loan program, and other Department of ED programs. NSLDS Student Access provides a centralized, integrated view of Title IV loans and grants so that recipients of Title IV Aid can access and inquire about their Title IV loans and/or grant data.

[8] Carla Fletcher, et. al; ABOVE AND BEYOND: What Eight Colleges Are Doing to Improve Student Loan Counseling; TG Research and Analytical Services; September 2015 http://www.tgslc.org/pdf/Above-and-Beyond.pdf

[9] Johnson, Carrie Lei. Do new student loan borrowers know what they are signing? A phenomenological study of the financial aid experiences of high school seniors and college freshmen. Dissertation. Iowa State University. 2012

[10] “Analysis of the Experimental Sites Initiative: 2010-11”. The U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid. Experimentalsites.ed.gov.

[11] Brown, A., J. M. Collins, M. Schmeiser, and C. J. Urban (2015). Evaluating the Effects of High School Personal Finance Graduation Standards on Credit Defaults.

[12] PISA 2012 Results: Students and Money (Volume VI) http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-volume-vi.htm

[13] Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor, The Economics Daily, Median weekly earnings by educational attainment in 2014 on the Internet at https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2015/median-weekly-earnings-by-education-gender-race-and-ethnicity-in-2014.htm (visited June 2017).