Weekly Checkup

March 1, 2024

ERISA Is the Bulwark Against Single-Payer

On Wednesday, the American Action Forum released my insight on the preemption clause of the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) of 1974 and its benefits to U.S. health care. ERISA’s preemption clause ensures that employers face lower regulatory burdens (and therefore lower costs) from state regulation, but it has faced challenges over the past several years with contentious Supreme Court cases and onerous state legislation. Let’s dive into the preemption clause to understand what it is, the disputes surrounding the meaning of the clause, and why it all matters.

ERISA preempts self-insured private-sector health plans from state insurance laws – in particular, those with mandates on plan design and administration. Self-insured health insurance plans are defined as those in which the sponsoring organization takes on the full risk of medical costs for beneficiaries, as opposed to fully insured plans, in which a third-party insurance company takes on the risk of beneficiary costs. An organization may contract administration of their self-insured plans to third-party insurance companies, but the establishing organization of that self-insured plan is still on the hook for all monetary risk.

ERISA’s preemption clause states that the statute “shall supersede any and all State laws insofar as they may now or hereafter relate to any” self-insured plan. Astute readers will note the applicability of the preemption clause hinges on the rather ambiguous phrase “relate to.” As my insight details, this ambiguity has led to more than four decades of Supreme Court cases that have attempted to clearly define what it means for a state law to “relate to” a self-insured plan. This has continued in the most recent ERISA Supreme Court case, the 2020 Rutledge v. Pharmaceutical Care Management Association ruling, which held a 2015 Arkansas law (Act 900) was not preempted by ERISA. Specifically, the Court ruled that Act 900’s requirement that pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) reimburse pharmacies for drugs at or above acquisition cost does not directly relate to the plan, but rather the plan’s PBM – separating this third-party administrator (TPA) from the plan itself. There are two issues with this: First, the Court seems to imply that payment calculation mandates are functionally cost impositions, not regulations on plan administration or design, and therefore not preempted by ERISA. Second, the Court appears to claim that TPAs are not actually part of the plan and therefore regulating them does not affect plan design and administration.

The biggest impact of Rutledge is that it created a perception of weakness in ERISA preemption through TPA regulation. Proof of this perception can be seen in the wide variety of new legislation states have introduced and enacted over the past several years eroding ERISA preemptions through regulations on TPAs. States clearly believe that Rutledge potentially provides a broader window for them to regulate and control ERISA plans indirectly, creating additional requirements, and therefore costs, for ERISA plans. The problem is not that the Court’s rulings are necessarily erroneous, however; the problem is that the “relate to” part of the preemption clause is simply too ambiguous about the limits of preemption. Specific to Rutledge, nothing in the current statute specifically identifies TPAs as a critical part of a plan’s administration. Indeed, TPAs such as PBMs were not used by plans to any large extent until over a decade after ERISA was passed. Now, self-funded plans rely on TPAs to function. The average company is simply not capable of negotiating its drug prices and provider networks, ensuring payments are made and rebates are collected, or the wide variety of other tasks that come with administering a health plan. As such, TPAs are essential to a plan’s operation, and the regulation of a TPA seems to functionally regulate plan design.

Congressional action is needed to clarify ERISA’s preemption clause and prevent unnecessary and costly regulatory burdens that threaten private companies’ health insurance offerings. As this author has highlighted before, the added expense of numerous state regulations means employers will likely either cut benefits, increase premiums and out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries, or both. This makes providing private insurance much less attractive to employees, who may simply choose to switch to government-subsidized Affordable Care Act plans. In fact, employees facing rising premiums and deductibles may begin to question the need for a private insurance system at all, increasing political support for a single-payer system. As the courts have struggled to provide a clear and consistent test for the meaning of “relate to,” it is time for Congress to act and provide one itself.

Chart Review: Oncology Drugs in Shortage as Reported by NCCN Centers

Anna Grace Shepherd, Health Policy Intern

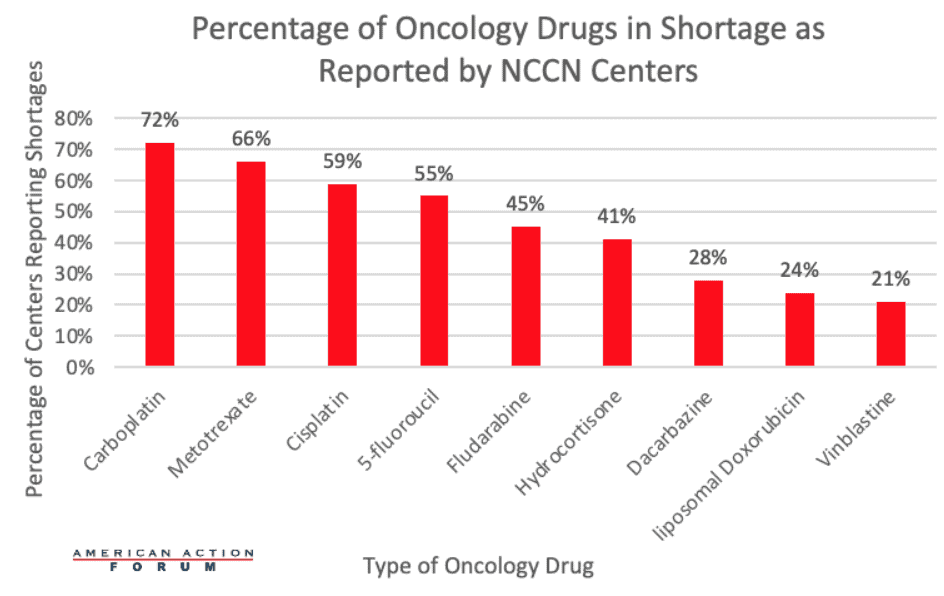

A study conducted by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) shows that of 29 NCCN participant centers, 89.7 percent were experiencing a shortage of at least one oncology drug. In total, centers reported shortages of nine different oncology drugs with carboplatin, methotrexate, and cisplatin being the most frequent drugs in shortage across the 26 centers.

As seen in the chart below, 72 percent of centers reported shortages of carboplatin, 66 percent of centers reported shortages of methotrexate, and 59 percent of centers reported shortages of cisplatin. During this shortage, only 64 percent of NCCN centers said they were able to give carboplatin to every patient who needed it, while 20 percent said they were able to give the drug to some patients, based on the severity and progression of their disease. About 63 percent of hospitals and cancer-center pharmacies characterize this shortage as “moderately impactful,” indicating that through substitution or rerouting, they can often get these treatments to their patients. Yet patients’ care could still be impacted, as many of the alternatives to the generic drugs in shortage have increased toxicity, worse side effects, or can compromise survival outcomes. Around 23 percent of hospitals and pharmacies characterize this oncology drug shortage as “critical,” meaning that they are delaying, canceling, or rationing treatments or procedures for cancer patients.

In short, consistent oncology drug shortages appear to be negatively impacting patient care and potential patient outcomes. Policymakers must continue to investigate the reasons for these persistent oncology drug shortages and work to find solutions without increasing the regulatory burdens surrounding the production of generic oncology drugs in the United States.